Palestinian artist Emily Jacir set up a very personal project in Bethlehem, in her home, an old house from the 19th century. It is a place with a long family history, and it now became an autonomous cultural center that functions, among other things, as an archive.

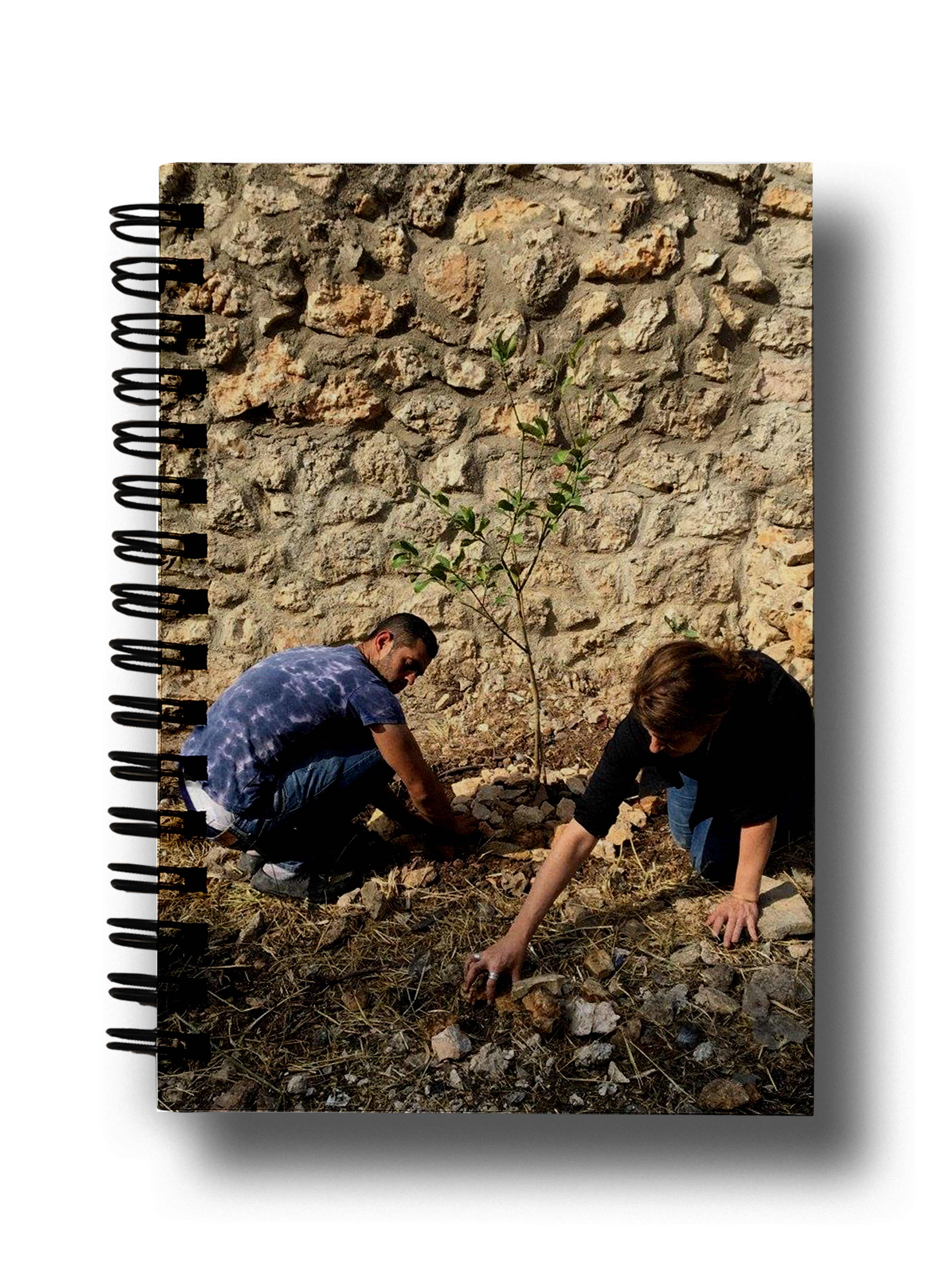

What is archived? Not only historic documents and local stories, the house also stands as a site for the collection of sounds from Bethlehem and knowledge around indigenous plants as they are collected by artists during their residencies. Think of an archive not only to preserve, but to negotiate a collective memory in the present.

Located on the bustling historic main road between Jerusalem and Hebron, just a few steps away from three refugee camps and the wall built by Israel in 2004, this house stands out as a resilient structure within a highly volatile environment.

The three women leading the Dar Jacir now, give continuity to the spirit of openness and the social and welcoming tradition that the family house always had – a characteristic that is remembered by many Bethlehemites and even people from surrounding areas.

Today, Dar Jacir has reopened its doors to the community, becoming a place for collective learning experiences and knowledge production, a place where all guests are participants and co-creators, a place that is connecting between past, present and future.

Or as Colum Mc Cann wrote in the article accompanying the project for the Visible Award: “Arrive today and the newly-renovated Dar Jacir house will whisper something about tomorrow”.

In the short video about Dar Jacir, you get a glimpse on the work of artist Sebastián Rawicz. He was inspired on site by the small, former storage building in Dar Jacir´s garden and he came up with the question of how to transpose the experience of that space.

This brings us to the first aspect of the project that we want to deepen:

Dar Jacir runs a highly site-specific art residency program. Each resident designs her/his own residency, having total freedom to work on what seems relevant to the surroundings and/or their personal practice at that specific moment in time.

Why is this so important?

The low-mediated residency program responds to the need for freedom in a difficult socio-political context: freedom to run an independent experimental program, without the obligation to meet the vision of foreign donors or local governments.

The artists we spoke to expressed their belief that the model developed at Dar Jacir sets an example and functions as an important prototype of how to work in such difficult contexts.

Faced with many unforeseen circumstances, residents highlighted how the situation caused them to develop a new perspective, both to the world and their own work. For example, Duncan Campbell described his residency as feeling “like a beginning, like scratching on the surface, removing a filter and shaking things up.”

Artist Michael Rakowitz’, with whom we also had the opportunity to talk about his experience, described the project like this: the Dar Jacir goes beyond surviving behind the apartheid wall, in isolation. It is about to continue to live, it is a resilient place.

Dar Jacir is creating a space of freedom and different thinking in this limiting situation and restriction that is in place in Bethlehem.

Besides the program that results from the artists in residence, Dar Jacir also has a strong educational focus through the organization of talks, workshops and masterclasses, which is crucial to Emily. Through the program at Dar Jacir Emily is trying to add to the education opportunities of institutions in the area.

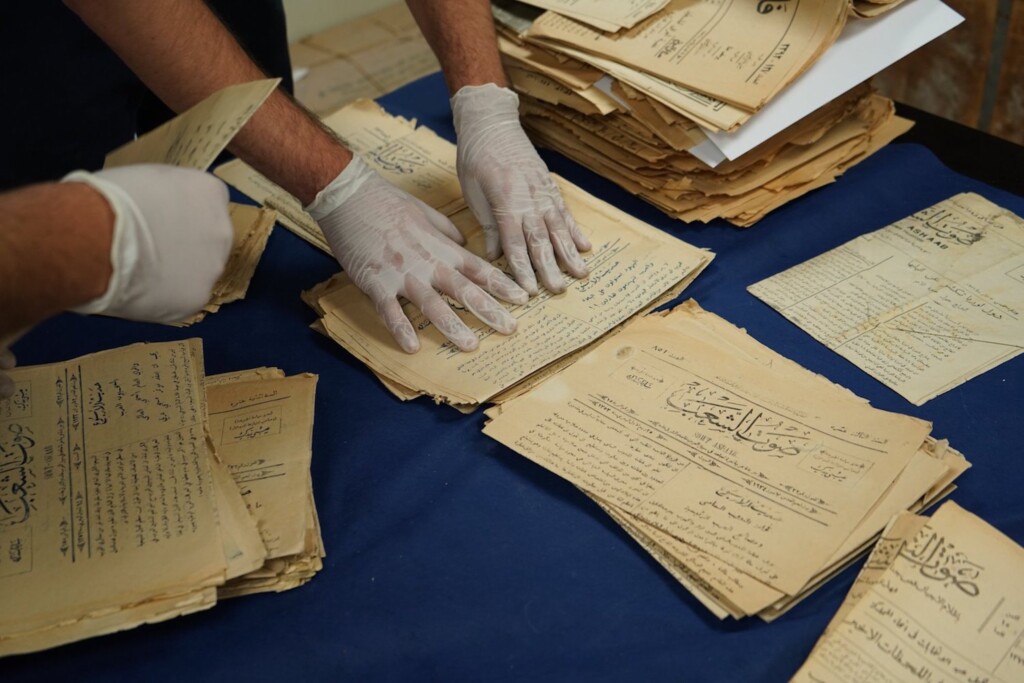

The video also expresses the value of the archive of documents located at the house. When talking with Emily, she told us a story of a tourist from Chile who was staying in a hotel nearby. After hearing about the Dar Jacir, he knocked on the door one day and said: Would you tell me about my family? This is because the Dar Jacir archive contains documents about the history of the half a million Bethlehemites who emigrated to Santiago, Chile around 1900, and were denied by the British the right to return to Palestine.

The archive also includes rare local newspapers telling the history of the city, and the work of Nasri Jacir, Emily’s grandfather, who was the only journalist in the Bethlehem area in his time. This material and information cannot be found in digital archives, or any other physical archives, as other local records have been stolen or destroyed. The archive is of high importance, as it gives Dar Jacir and the wider community of Bethlehem, ownership of their own history.

This brings us on to the Award. Emily explained us, what huge effort is needed, to properly map and make the material accessible for research and research-based art. Think of how delicate the material is. It needs professional technical expertise, which could be supported by the Visible Award.

Furthermore, the Award would allow Dar Jacir to register as its own legal entity, helping the project access more funding and gain greater independence.

Dar Jacir fills the lack of exposure to cultural practices, local and international, in the Bethlehem area. And it creates a two-way exchange, bringing new understanding about the reality facing Palestine. Dar Jacir needs support to develop further programming and to elevate and explore the importance of independence, collective memory and self-sustainability.

List of sources:

Dar Jacir. “Dar Yusuf Nasri Jacir for Art and Research.” Last accessed November 10, 2019. https://darjacir.com.

Visible. “Dar Yusuf Nasri Jacir for Art and Research – Emily Jacir.” Last accessed November 10, 2019.

McCann, Colum. “The Art Piece. A text on Dar Yusuf Nasri Jacir for Art and Research.” Last accessed November 10, 2019.