Matteo Lucchetti & Judith Wielander: The Festival de Performance has a temporary, immediate, and corporeal nature that offers the possibility to seamlessly interact with the urban laboratory of a city in transformation. This description may explain why you have chosen to utilize the format of the performance festival since 1998 to examine the context of Cali and Colombia. Considering the extent to which this context has changed in recent years, is this format still relevant?

Helena Producciones: We all met for the first time in 1998, and quickly discovered that we shared many interests and concerns. After numerous discussions, we realized that it was important for us to establish a concrete position in reaction to the situation of artists at that time. The precarious conditions and lack of effective institutions to promote contemporary art in Cali made it necessary for us to produce this event as an option and a real possibility. The fact that we were friends, and that Cali’s characteristically warm weather facilitates an outdoor culture, are both important factors that should not be underestimated. The very first Festival de Performance actually took place in 1997 and was organized by Juan Mejia and Wilson Díaz. We feel that it continues to be relevant because the platforms to produce (not just represent) culture are still lacking.

ML&JW: Before attending the festival it was our understanding that the format offers the audience a diverse and eclectic program; however, once there we realized that the festival also functions as a public parade, a carnival, and a demonstration. In other words, it comprises a series of events where every member of the audience is also a participant. For example, we were alternately guests at a wedding, tourists in the Siloe neighborhood, zoo visitors, and witnesses to a political act in which a protestor threw a water bomb at a corrupt public figure. Has Helena Producciones become increasingly aware of the public’s role in the festivals?

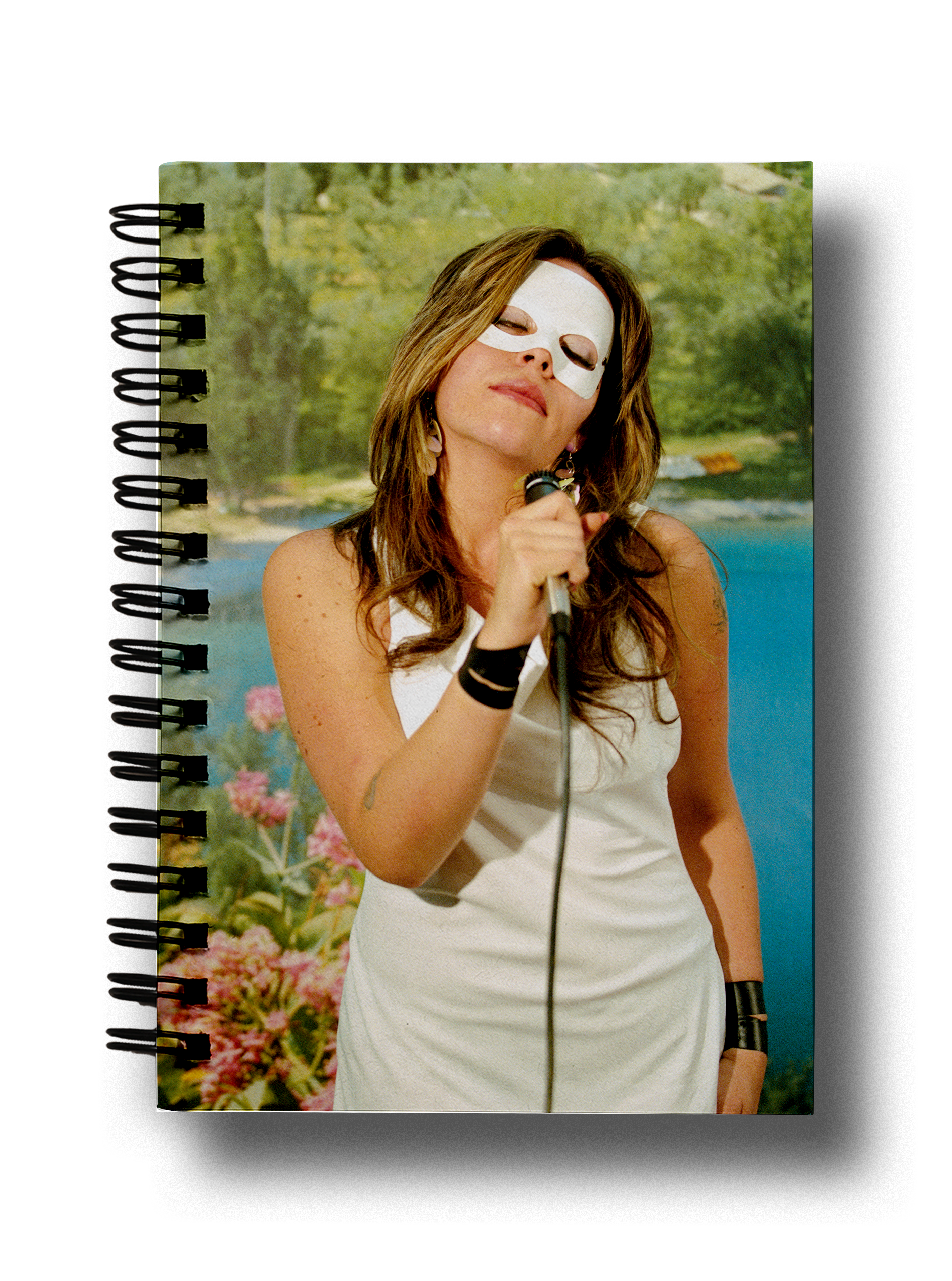

HP: We have always been very aware of the public’s role. Given that the festival seeks to address issues regarding artistic practice—the artist as a worker, power relations, and the role of institutional critique in Colombian art—we consider the spectator to be a capable and significant participant. A good example of this is the format of the one-day performance marathon, which represents an experience of catharsis—both conceptual and physical—shared by both artists and spectators. Proposals range from what we typically think of as performance to actions, concerts, workshops, installations, and so on so that the event resembles a community fair or carnival more than a conventional art event.

ML&JW: Given the sense of proximity to the public that is endemic to the medium of performance, can you identify a history of participation through these moments of social proximity that you have encountered over the years?

HP: It is not the festival as an abstract entity that has connected with the audience; rather, the artists themselves have understood and emphasized this relationship, which is always individual and very personal. In this sense, the artists conceive different types of viewers, and this helps shape the public. Likewise, the festival has generated platforms where community projects and citizen participation interact with artist projects, enriching one another, but always doing so with humor in order to question the very boundaries of art. This allows the public to solicit whatever it wants from the festival.

In the first Festival de Performance in 1997, each artist who desired to participate in the event could do so as there was no elimination process. At the time, Juan Mejia and Wilson Díaz were professors at the art school, so giving students the possibility of acting as artists in a public forum set a tremendously important precedent. Additionally, the different spaces utilized for the event—a school theater, the official museum, a former aguardiente factory, an old flour mill—influenced the development of each performance.

arrow_upward

arrow_upward

arrow_upward

arrow_upward

ML&JW: The art students who attended the first festival later became members of the collective; today, the festival is an important reference for local art students during their formative years. How significant is the intergenerational aspect of Helena’s activities? Are your projects always open-ended or do individual authorships have a strong impact on these activities?

HP: One of the first goals of the festival was to enable students to work as practicing artists, as we came out of a context in which the conditions for making art have always been too ambiguous. The festival provided a much-needed impulse in this sense. Within the collective itself, there are no hierarchies so that our different positions become assets. Additionally, each member of Helena pursues an individual practice that helps nourish the group as a whole. A collective with a sense of common purpose is more than just the sum of ideas of its constituent members.

We must also acknowledge certain shortcomings, like the anonymity of certain members in favor of other more high-profile ones. This is something we strive to avoid by providing the conditions in which the individual practices of each and every one of the collective’s members may flourish. So we promote the work of our members through our platforms because the idea is not to simply function as producers of events, like an amorphous and nameless institutional entity, but to achieve certain conditions that we, as artists, can also benefit from.

ML&JW: The festival is now fifteen years old, and over the course of eight editions it has resisted institutionalization. Some of its original components have survived—like the one-day performance marathon—while new activities, such as La Escuela Móvil de Saberes y Práctica Social de Helena Producciones (Helena Producciones Traveling School of Shared Knowledge and Social Practice), have been included within the frame of the festival. How have you mediated the desire for legitimacy and recognition while maintaining the freedom to experiment?

HP: The very nature of Helena is experimental: it is how we started, and we continue to look for answers and to question certain structures that are often taken for granted. We are constantly confronted by new, sometimes unexpected issues. These experiences have been shared with those individuals and groups who have participated in our projects and proposed new ways to connect with our initiatives. Both aspects—legitimacy and experimentation—are mutually dependent upon one another and provide the necessary conditions within which Helena can continue to exist.

ML&JW: Would you explain in detail what the Escuela Móvil de Saberes y Práctica Social is all about? Has it continued after the Festival?

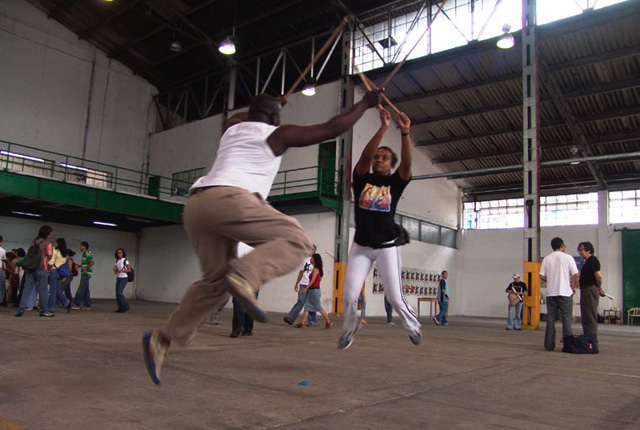

HP: The Escuela is an initiative that is based on an observation of how art is connected to its particular context, while also considering the problem of funding in Colombia. As a pedagogical initiative, it encompasses education, adventure, exploration, and methodological issues through a series of borrowed formats. The school attempts to investigate the needs and expectations of both artists and non-artists. It desires to disrupt preconceptions by exposing their ideological, social, political, economic, and cultural roots through a collective process of self-exploration. The school is autonomous and coexists both in tandem with Helena as well as separate from it. As a collective, we utilize the format to best respond to a given situation. The school often transcends events like the Festival de Performance and moves off in its own direction.

ML&JW: The production of art within the public sphere, especially involving artists invited from abroad, demands a clear understanding of the rules and dynamics that regulate Cali’s public domain and social fabric. How have these rules changed, and how much bureaucracy is part of the everyday life of Helena Producciones?

HP: The local context has undergone various transformations. Ten years ago, the ways to address and understand the public space were very different. Cali is a city that desires to inscribe itself in a global context, and yet it remains very provincial in the way its local institutions operate. The requirements for access to public space have become increasingly Kafkaesque. Helena identifies Cali not only as its geographic base but also as a political and historical subject of investigation. We are interested in exploring the city’s future, the use, and misuse of its architecture, the failure of those civic values proposed during the 1960s and ’70s, and the problem of access. In preparation for the last festival, we had to obtain twenty-one permits, which meant spending a considerable amount of time climbing up and down the stairs of government buildings. These are hurdles we have to face and to cross with patience and humor.

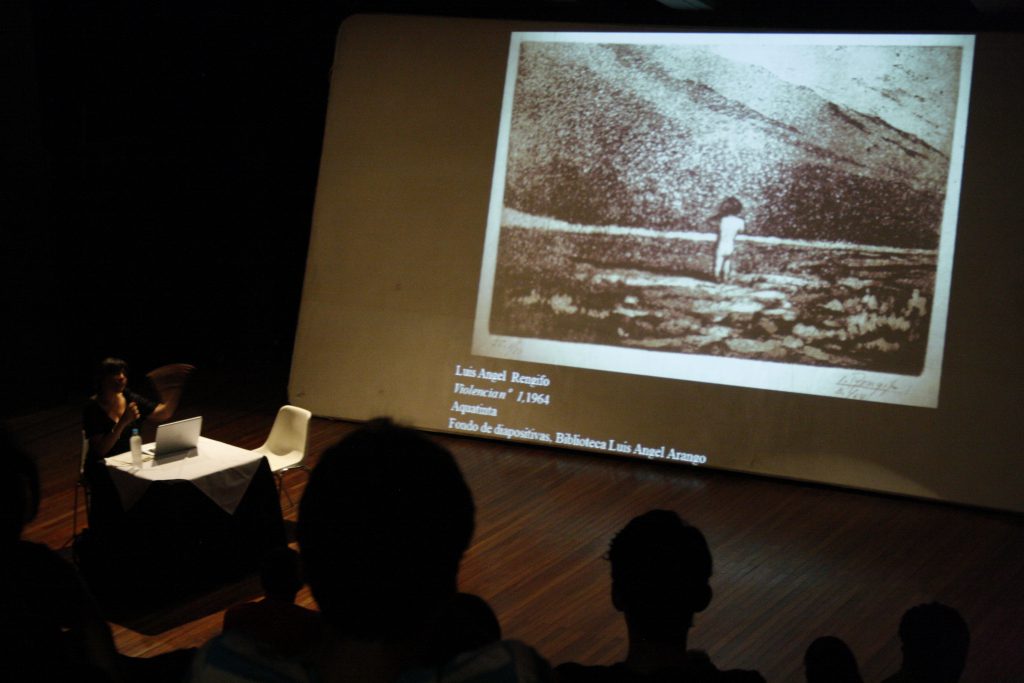

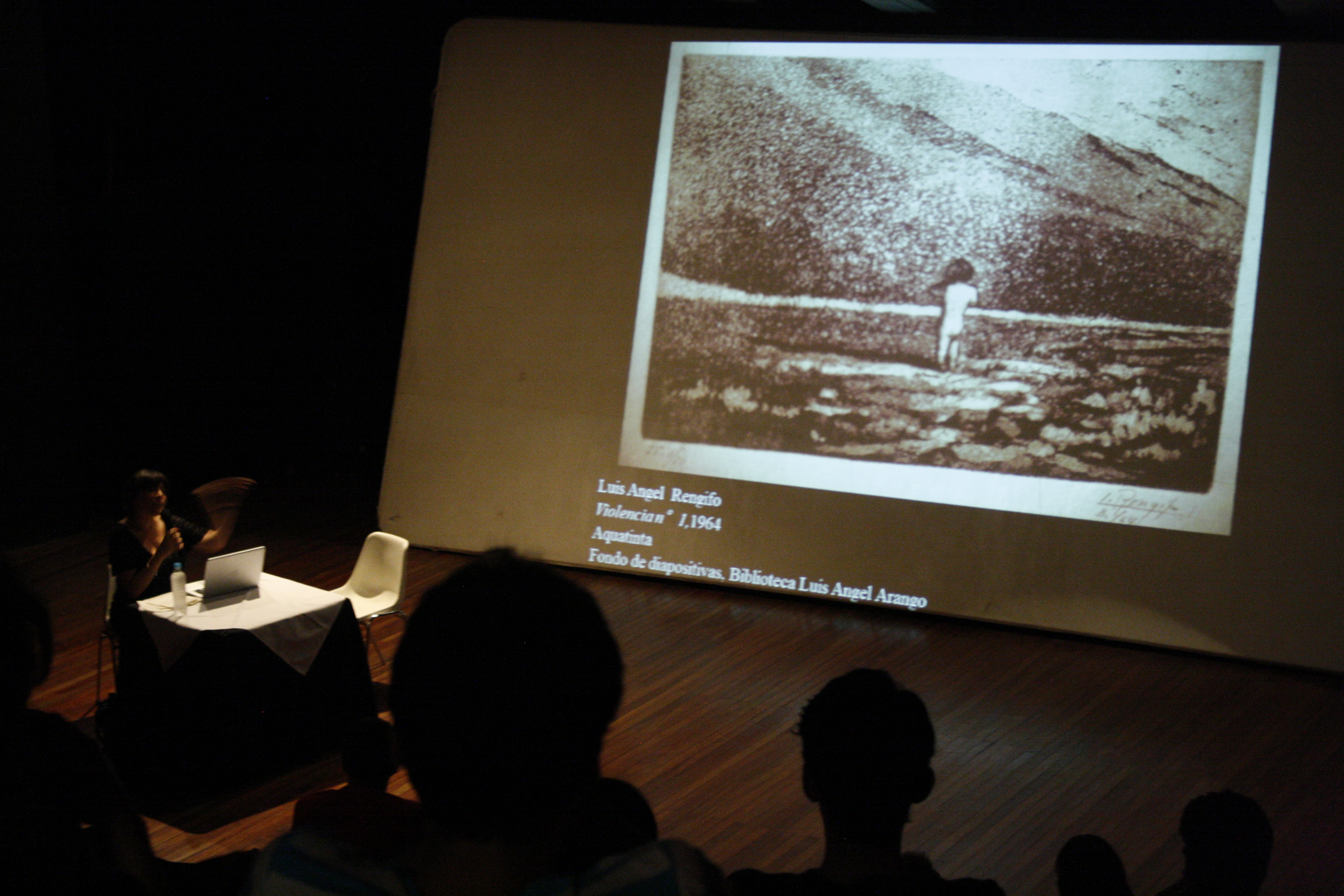

ML&JW: The most recent edition of the festival focused on the Colombian avant-gardes of the 1960s and ’70s, and on the selective amnesia that has excluded these artistic practices from conventional art-historical narratives. Given that the teaching of recent art history is a relatively recent phenomenon in Colombian universities, did you feel it was urgent to address the censorship of politically-engaged practices that took place in the 1980s?

HP: In a sense, the festival has always engaged with the particular problem of the exclusion of certain narratives from the canon. It always responds to specific concerns of the local artistic milieu concerning education, research, spaces of participation, exchange, exhibition codes, and the meaning and function of art. With each edition, the festival seeks to address the artistic, cultural, and institutional void by further evolving as a legitimate space. Unfortunately, the transformation of the city has not yet produced sufficient conditions in which the life and work of artists can develop. Conflicts have not been resolved; rather, they have mutated and acquired new forms that demand review, observation, and reflection, as well as concrete solutions.