Trampoline House is an independent community center based in Copenhagen, Denmark. But it is much more than that. In a European climate governed by normalised hostility, criminalization and dehumanization of asylum seekers and migrants, it is the only support structure in place that uses art as a possibility to revert the damage caused by Danish migration policies and reshape political realities. Because of a deliberate lack of public funds, it is currently at risk.

Trampoline House was founded in 2009 by artists Morten Goll, Joachim Hamou and curator Tone Olaf Nielsen. The project was born from the act of listening to asylum seekers’ experiences and collectively putting together an answer to their needs in the form of a program.

Denmark has one of the world’s most aggressive migration policies. No public resources are allocated to cater to asylum seekers’ needs during their asylum processes, which can take up years. Instead, they are held in detention camps and denied the most basic rights, such as the right to work, education, the right to a home, or even to decorate their rooms or cook their own food. In short, they are denied the right to a life.

In the words of the Danish immigration minister Inger Støjberg: ‘we intend to make conditions for people in the asylum system unbearable’. And in the words of the house’s users, ‘Trampoline House is a home’.

At present, it is the only space providing a model for contact, hope and integration between asylum seekers and Danish society. Trampoline House works in four ways, which influence and sustain each other.

1. It provides physical, mental, and legal care through offering counselling with volunteer lawyers, doctors, and psychologists.

2. It uses the domestic and the every day as space to give care, capacity build and socialize. This is done through different activities: for example, through the open cooking workshops, which are offered by migrant women, or the Danish language lessons, which are designed for migrants.

Everyday activities in the house – cooking, cleaning, teaching – are carried out through an exchange system where you give your time and labour in exchange for the things you receive. The idea is to give back to the community on equal terms.

3. They also work through campaigning and direct action. For instance, their proposal to change the law to grant rights to asylum seeking was recently approved in the Danish parliament.

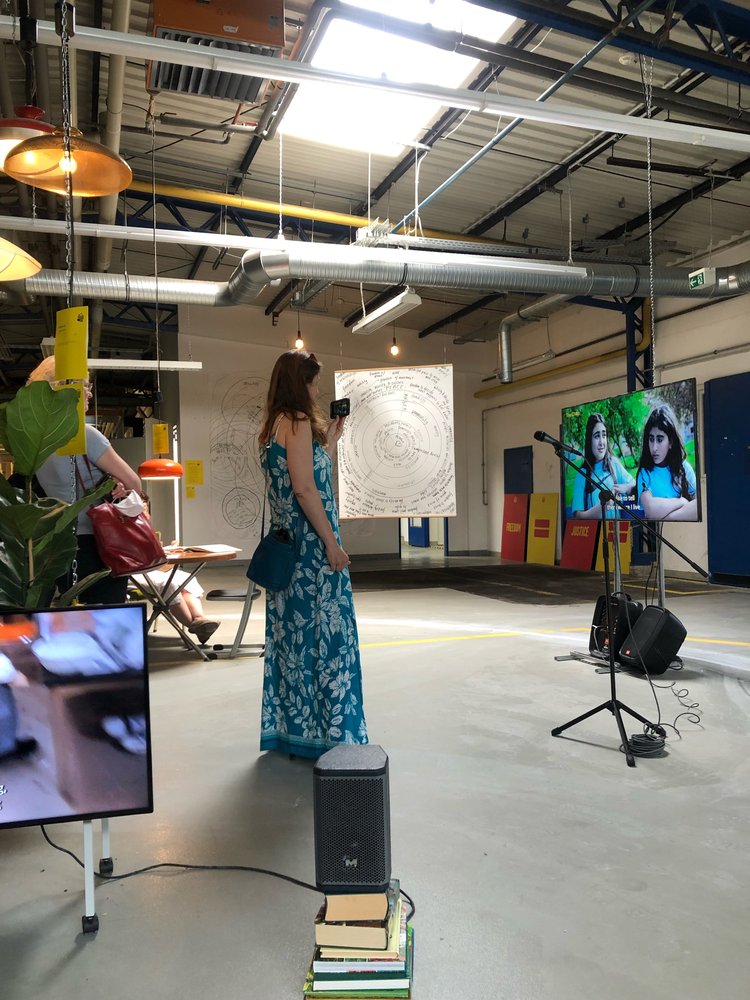

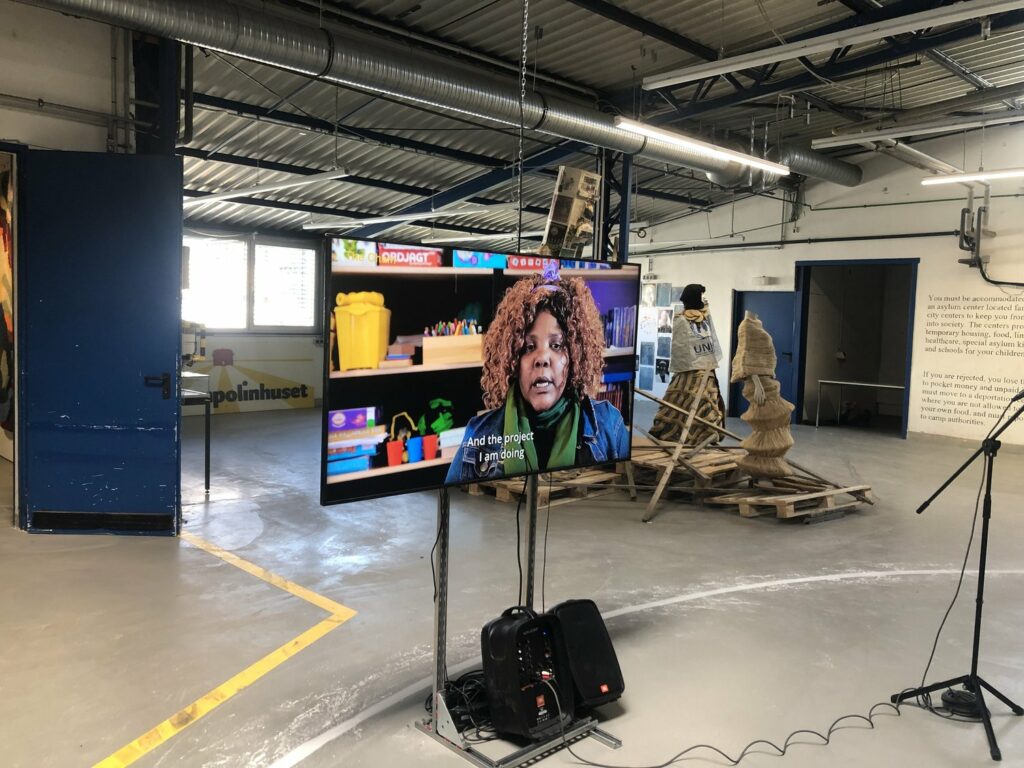

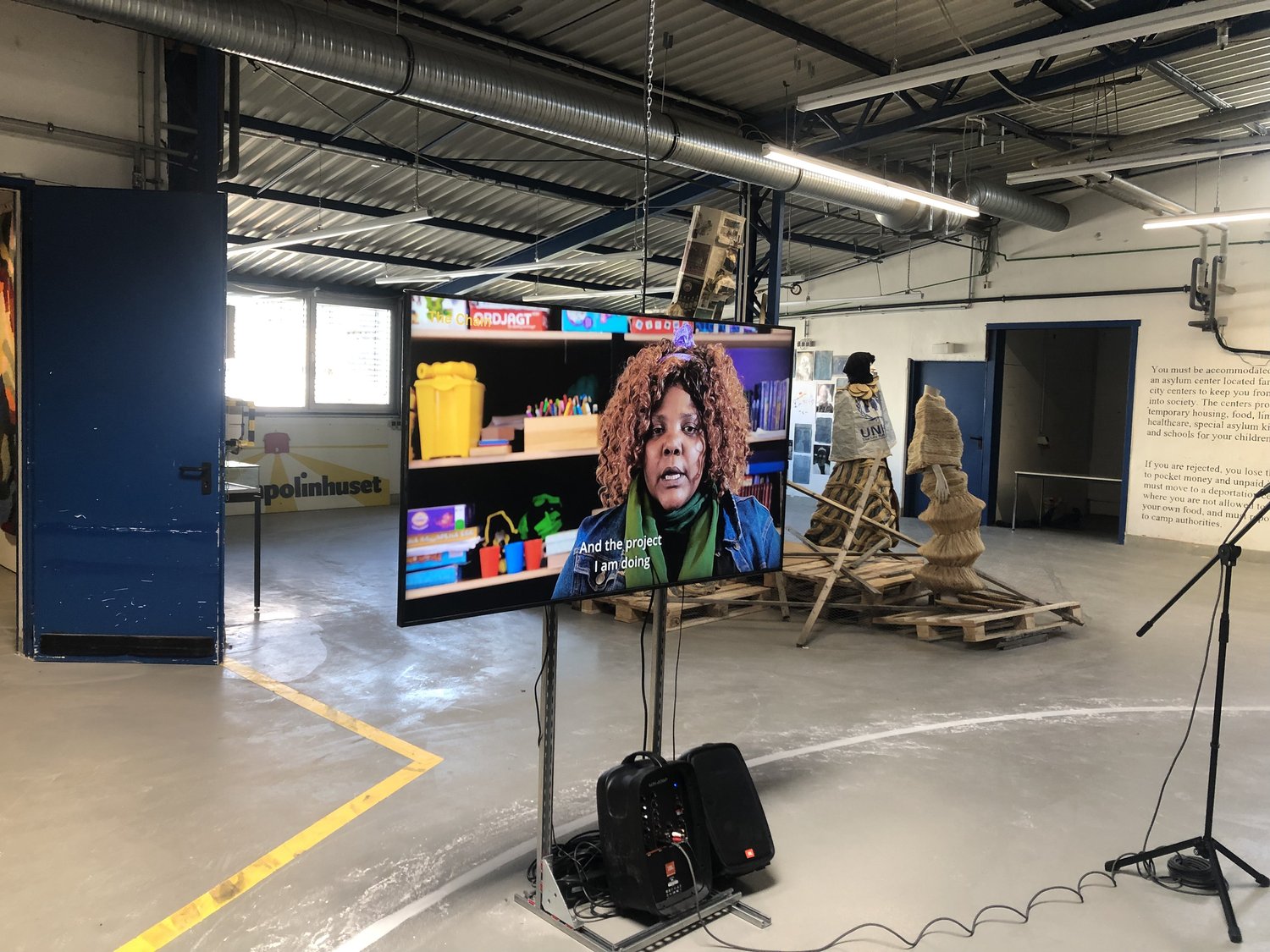

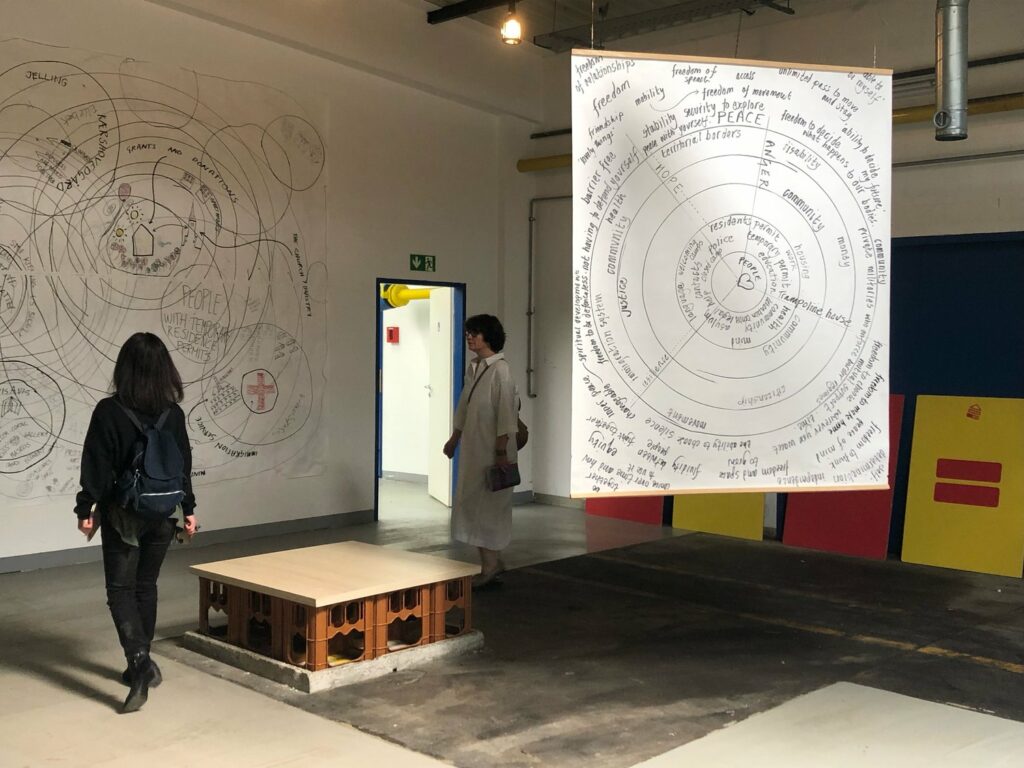

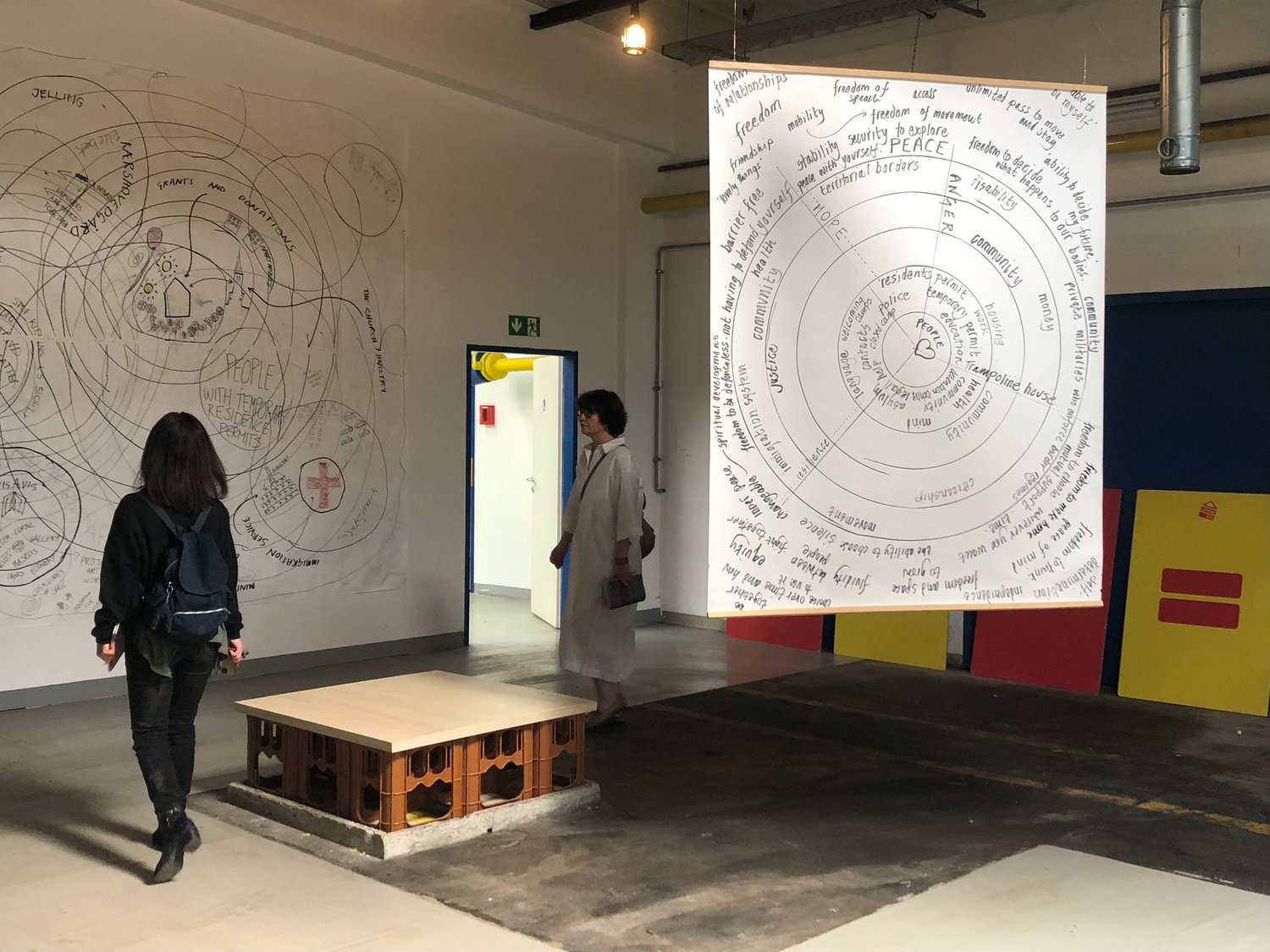

4. Through CAMP. CAMP, which stands for Center for Art on Migration Politics, is an exhibition space which discusses questions of displacement, migration, immigration, and asylum. The centre produces exhibitions with both renowned international artists and less established practitioners, prioritizing artists with refugee or migrant experience. Located within the premises, it’s meant to be a point of encounter between these two audiences, and to mobilize the artworld as a space for political change.

In terms of its curatorial rationale, it’s important to say that Trampoline House is a curated project that aims not to speak about, but to speak with and from refugees and asylum seekers. It mobilizes feminist and decolonial strategies to sustain a relational space that is filled with the practice of care. Enabling this space is the fundamental element of its artistic practice. In the words of artist Tania Bruguera, who will be a guest curator at CAMP in 2020, Trampoline House sees art ‘not as an event, but as a culture of implementation of new horizons’.

We experienced this personally during the curatorial process by speaking to Shakira. Shakira – whose surname cannot be revealed because it would put her case at risk with the Danish authorities – is a rejected asylum seeker from Congo, who has been living in the deportation camp of Sjaelsmark for 3 years with her 10 year old son. For her, the space is about ‘feeling ‘seen’, ‘needed’ and ‘free’. It’s the only space where her mind is at peace, where she can can gather strength. Speaking to Shakira enabled a form of relation and commitment between us that didn’t exist before. It also underlined the capital importance of the centre for their emotional wellbeing. In Shakira’s words, ‘if the house shuts down, our lives will shut down too’.

On this note, there is one last key issue that conditions Trampoline House – its economic vulnerability. While the house has been established for ten years and it has a large structure currently employing 20 people and housing about 200 users and 80 volunteers, its economic situation is precarious. Because of the kind of work they do, which legally falls between the categories of artistic and NGO work, Trampoline House is a fragile ecosystem that is always at economic risk. They have recently seen their budget slayed by half – as the Danish government has applied 50% budget cuts to all NGO funding – and because of this, it is struggling to survive in 2020.

In conclusion, Trampoline House is a radically caring ethical, artistic and political project. It is a brave step to come out of the white cube and into life, making refugee populations visible, holding governments accountable and reshaping reality through affect and implication. It is is both an urgently needed support structure and a model for societal transformation, not only in Denmark, but in the whole of Europe.

¹ Tania Bruguera, citation in conversation with Tone Olaf, October 2019