Our houses tell stories. Dar Jacir makes you want to listen. It lies at the edge of Bethlehem in the West Bank within a canister’s throw, or a stone’s throw, or a flower’s throw of what is called the Wall. It is a large, beautiful limestone house. The stone is cut from nearby quarries. The doors have an honest heft. The ironwork is intricate. The ceilings invite you upwards. You step through the large rooms. Others have been here before you. They are glad to invite you in. These people are composed of light somehow, not just random packets of light, but long, complicated, shadow-shifting rays. You remain at the window and open the shutters. That could be a valley or that could be a watchtower or that could be a marketplace or that could be a refugee camp or that could be an olive grove or that could be a checkpoint or that might be all of these at once.

Dar Jacir was built in the late 1880s and renovated in 2018. An elegant mansion on the historic Jerusalem–Hebron road, it was the home of Mukhtar Yusuf Jacir, the designated mukhtar, or village head, of Bethlehem. He was the town’s registrar and trustee, a member of the Faraheeya clan, one of the seven original families of Bethlehem. It was a thriving town, not least because it was the birthplace of Christ and a crucible of cultures. The house lay at the entrance of the city on the Jerusalem–Hebron road. Pause here a moment. Enter through the wrought iron gate. Take the steps. Stroll through the garden, along past the stone retaining walls. One can sense the open door, the rope bell, the expansive tables, the fine china, the peal of laughter from an upstairs room. Travellers come and go. Cart, donkey, camel. Soon there will be cars. The mukhtar is Palestinian. Of the Ottoman empire. Like all empires, it does not recognise its own fall. The British come and the British go. New generations of the Jacir family take over the house. They too open up the windows. There are weddings, there are births, there are funerals. Food is served to the weary travellers as they pass outside. It is a family home. See there, a ladder leaning up against the olive tree. See there, a child’s bicycle with the wheel still spinning. See there a mother-of-pearl clock.

Time ticks within time. Borders are drawn and redrawn. There are wars—1948, 1967, 1973—but the house still stands, a Palestinian house on the border of encroaching settlements and shifting political lines. A refugee camp is located in the fields behind the house. A small checkpoint is installed half a mile down the road, but the road is still open to Jerusalem.

Step inside again, away from the wars. The house is loud now with art. There is a dinner party, there is candlelight, there is argument, there is defiance, there is perseverance, more laughter. Stories are being told. Friends and family members who have gone away, some to Italy, some to Chile, some to other parts of Palestine. A child draws a picture. A child finds a camera. Another generation comes and goes. There is an uprising, an intifada. Stones are thrown. Another intifada. Bombs explode in far-off cities. Down the road, the cursed checkpoint grows and grows. A wall is built. Some call it the Separation Barrier, others call it the Apartheid Wall. This house can tell so many stories. It knows languages. It knows dispute. It knows what it means to survive.

Arrive today and the newly-renovated Dar Jacir house will whisper something about tomorrow.

Under the guidance of Emily and Annemarie Jacir—both spectacular, world-renowned artists—it has become a non-profit home for artists from all over the world. Yes, it is in the shadow of Checkpoint 300. Yes, it backs up onto the refugee camp. Yes, there are protests sometimes right outside on the Hebron Road. Yes, the Israeli army drive tanks down the road and spray the house walls with Skunk. Yes there are gas canisters to be found in the garden. Yes, the settlers sometimes come and eye up the property. Yes, there are bureaucratic delays. Yes and yes and yes. And yet.

The Dar Jacir house is an art piece. It speaks to the idea that art is necessary to prevent beauty from drifting into oblivion. It is an act of resistance. It is a showcase of grace under pressure. It is a house that thinks contrapuntally. It poses questions. It doesn’t force answers. It is art at work in the social sphere. It forces us to rethink. We are not slouching towards Bethlehem anymore.

The desire is, in the words of Seamus Heaney, to make ‘hope and history rhyme.’ The natural arc of art bends towards justice. The house tells its stories and invites others to tell more. This is the way the world unfolds and changes.

arrow_upward

arrow_upward

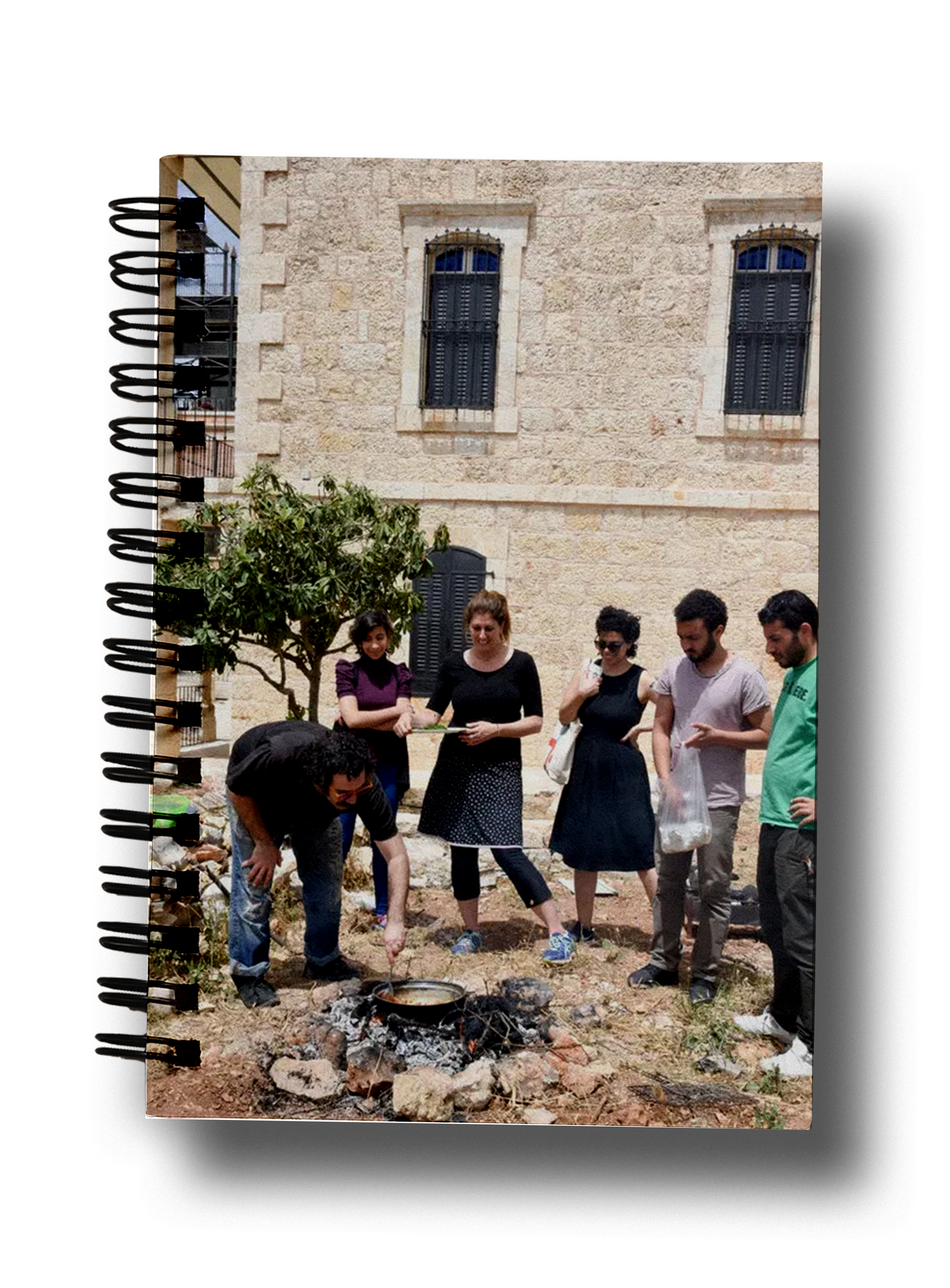

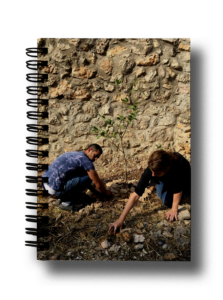

Dar Jacir has opened its doors to filmmakers, writers, poets, scholars and artists of every stripe. The artists in residence get a chance to breathe in all the stories, past and present. The resident artists are introduced to the community through the heroic linking work of Emily Jacir, so that art meets artist meets community. The Yusuf Nasri Suleiman Jacir archives—a vast collection of rare material from the past two hundred years—are open to all visitors. There are diaries, photographs, newspapers, personal letters, ledgers, records. Locals are invited to come in and breathe in the taste of a culture that has been assaulted in recent times, but has somehow persevered. The centre has served as host for the Haifa Independent Film Festival, FilmLab, Narrative 4, PalFest and several other cultural organisations. It also invites landscape artists to work in the garden and to teach children from the Aida refugee camp how to work with local plants and to initiate an urban farm.

The house, then, is a place in which the history and the contemporary conditions of Bethlehem—and all the connotations of that name—meet. It is a learning hub for the community and beyond, a place to grapple with the tiny and the epic both.

Step inside. Walk along the corridor. Pass the kitchen into the living room. Gaze out towards the back door where the light is slant. A line from Rumi somehow penetrates the air: ‘Out beyond ideas of wrongdoing and rightdoing, there is a field. I’ll meet you there.’

Colum McCann