Daniel Godínez Nivón’s work with the historical iconography of Mexico and with indigenous groups develops a novel approach to a long tradition of Mexican artists engaging with these themes and social actors. Since the nineteenth century, and most famously after the Mexican Revolution, artists incorporated native peoples into their works, questioning how to represent them and to interact with their culture. Before cinema, television, and anthropology interpreted the place of indigenous people in the development of the nation, visual artists and writers were the ones documenting their lives. They continued to do so when the communication industries and social scientists became the main builders of these peoples’ image. Diego Rivera’s murals, which made the natives visible in the national palaces, Francisco Toledo’s pictorial reinventions of the myths and juchiteco¹ eroticism, and Graciela Iturbide’s photographs which present the world with surprising visions of indigenous peoples’ faces and rituals are culminating moments of this intense connection between visual arts and Mexico’s ethnic groups.

Why, in the age of computers and mobile phones, in which indigenous peoples record their lives and communicate with migrants, do painting and photography continue to play a leading role in what is said, read and seen about indigenous populations? Firstly, because new technologies do not replace older ones: theatre and dance did not disappear with the emergence of cinema, nor was cinema displaced by television or did digital screens make us forget traditional media. Popular, rural and urban practices, such as those of university students, are developed both online and offline. Technological innovations relocate old forms of communication. While some—VHS, the fax—disappear, the key question is how these forms of communication coexist.

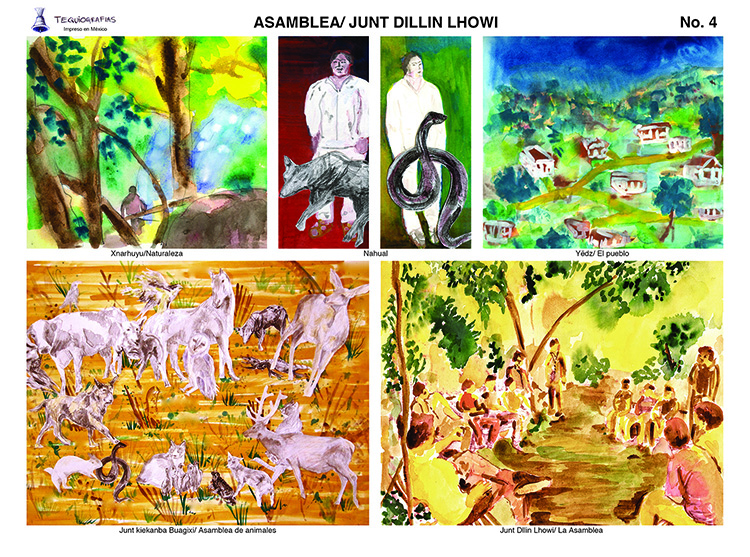

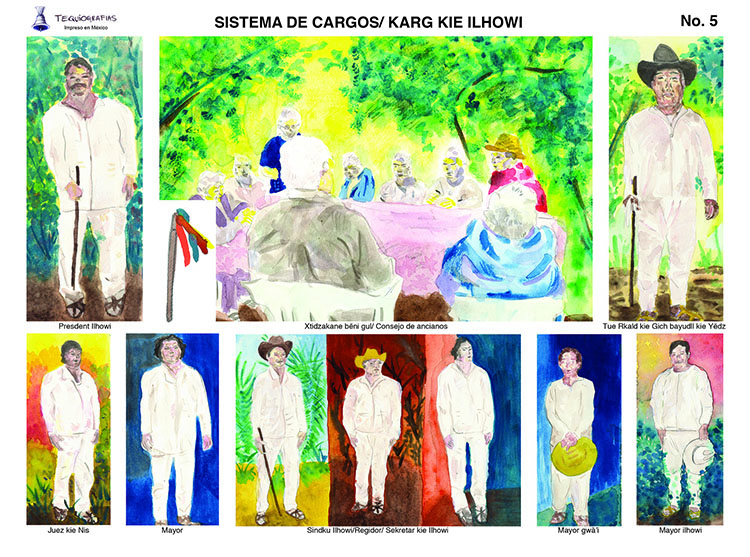

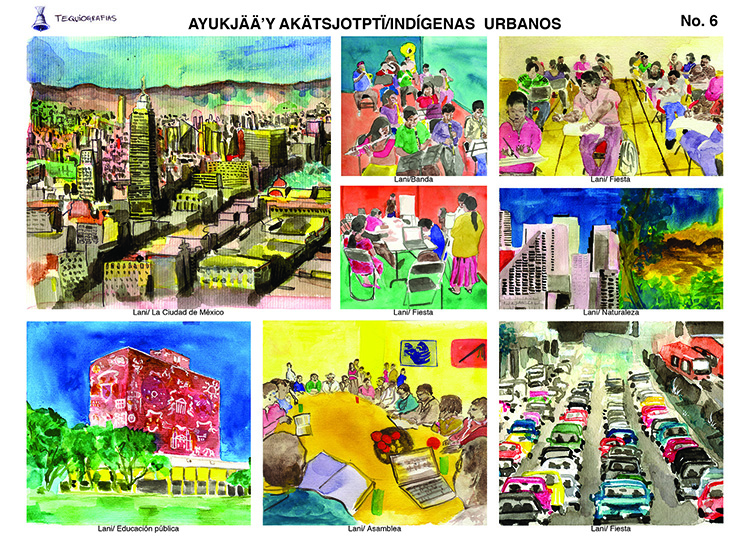

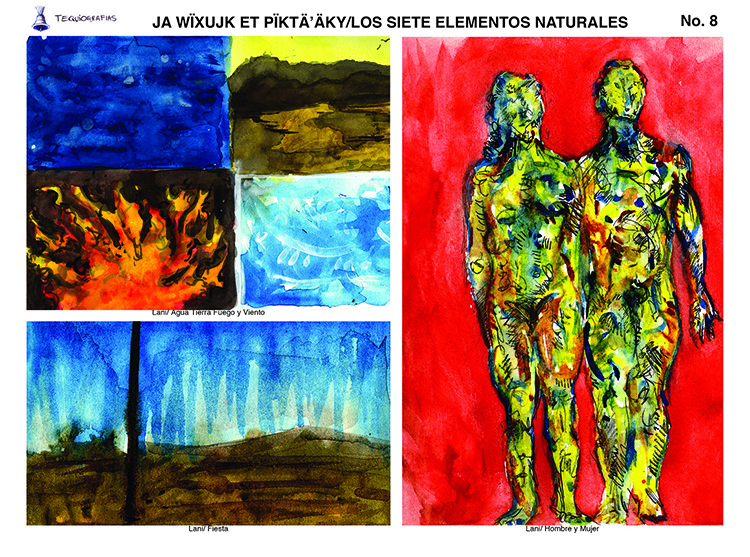

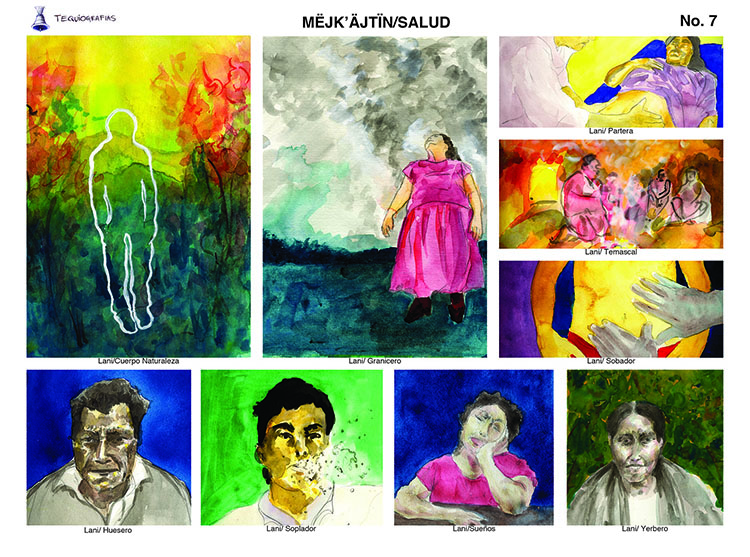

Monografías escolares (school monographs) which summarize on a printed page in colour on one side and black-and-white on the other, information on historical events, figures and geographies, continue to be sold in stationery stores, in schools and for assignments at home. Their massive production has led to the stereotyping of ethnic groups. Neither those who continue to live in their native lands nor migrants to cities that must use them for educational purposes feel represented by them: ‘That’s not my body’, ‘That’s not how I see myself’.

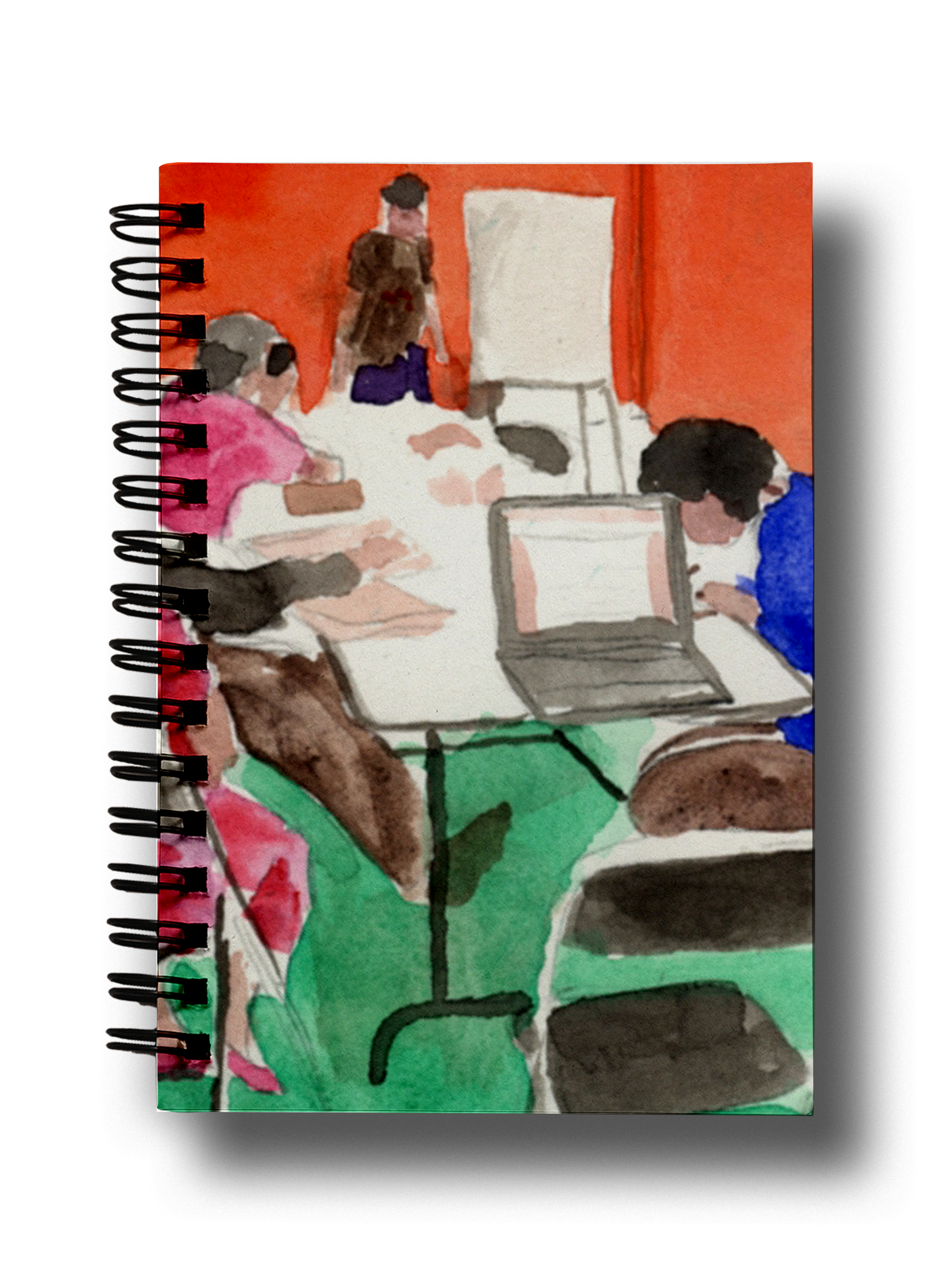

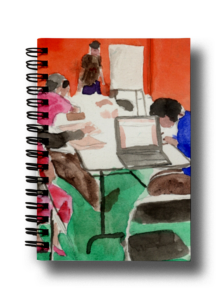

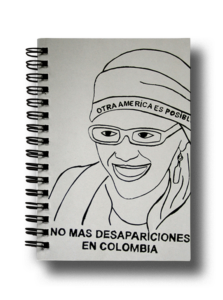

Daniel Godínez engaged in a dialogue with migrant indigenous groups in Mexico City to rework both their texts—which are bilingual—and illustrations. In meetings with four ethnic groups organized in the Assembly of Indigenous Migrants (AMI), he tried to develop their own monographs with them. He spoke with directors and teachers of elementary schools to interest them and convinced nearby stationers to sell them. He made the Ministry of Public Education adopt them in the practices of indigenous teachers in some states. He also developed critical studies on the ways in which ‘mestizo’ or Westernizing visions are created. He did not rule out including some references or visual approaches from modern art.

I asked Daniel, ‘How did you decide when a certain aesthetic treatment of the figures is legitimate because some remind me of Impressionist references?’

‘What matters is living knowledge—the media—and the decisions adopted by the Assembly. In the Assembly, the vitality and richness of colour are important. That is the reason why some maintain their chromatic excess.’

This collective work gives its meaning to the name Tequiografías coined by Godínez. The tequio, which comes from the Nahuatl term tequitl (work or tax), was a task forced upon the Indians during colonial rule. This obligation to participate without pay in the construction or maintenance of public works (buildings, churches, roads) was redefined by the indigenous communities to designate tasks of unpaid social service, in which men older than sixteen are involved. Collaborating in this way gives them prestige before the community and is usually taken into account when attributing positions of authority: in Oaxaca this practice was incorporated into the political constitution.

In the original ethnic zones, the tequio refers to a way of relating to the land, transcending the work of family subsistence and generating shared services, such as the provision of water, light and roads. Many migrants to cities incorporate it to improve their areas, affirm community identities and create media such as magazines, newspapers and websites. Even the heads of households or children who migrate to the United States participate in this. They communicate with their community, receive daily news and festivals or sports tournaments, and share stories of their migrant experience².

The Tequiografías bring together the traditional technique of school resources, in terms of structure and format, with the sense of community and collective deliberation about content and style. Unlike the industrial production of monographs sold in stationery stores, they are not controlled by the Ministry of Public Education, which sometimes tried to eradicate them and promote consultation in libraries to obtain ‘true and complete information.’³ Daniel Godínez’s programme recognizes that school habits, children and families legitimize them. Its objective is to recreate these monographs in collaboration with the communities. Instead of discriminating against this commercial diffusion of knowledge due to its lack of rigour, it seeks to de-homogenize it, making it possible for different ethnic groups to add in their self-perception and their way of being. In addition, it contributes to recognising diversity and pluralising the meaning of Mexican stories. Furthermore, some migrants periodically take Tequiografías used in Mexico City to their native communities, such as Tlahuitoltepec, San Juan Tabaá, Yalalag and the city of Oaxaca.

His drawings—or transcriptions—of the urban towers, the metro, the congestion of the streets and emblematic buildings such as UNAM (National Autonomous University of Mexico) transmit not only information about what the city is like for future migrants, but also how the indigenous people experience it. By differentiating themselves from the visual reading of the megalopolis broadcast by television or cinema, they suggest that whoever comes from another place can reorder meaning from their own culture.

After a decade of work, with the limitations of an individual project with finite support, the Visible Prize would allow Daniel Godínez to expand his undertaking. In the interview we did to prepare this note, he told me that it would contribute ‘to the consolidation of the Tequiografías’ and also ‘to benefit other projects that the AMI maintains, such as the formation of philharmonic bands and the promotion and teaching of their language.’

Few indigenous processes, such as Zapatismo, or migrants, such as the caravans of Central Americans that cross Mexico with the intention of reaching the United States, receive media attention and international solidarity. This venture that seeks to renew the links between art, representations of indigenous peoples and educational processes, has thus far only benefited a few regions, such as Guanajuato, where Godínez distributed ten thousand Tequiografías to primary and secondary public-school teachers. The requested support would facilitate a national amplification of the project to other ethnic groups and also allow it to reach migrant communities in the United States, extending an intercultural understanding of indigenous cultures.

Néstor García Canclini

¹Juchiteco is the demonym of people born in the town of Juchitán, Oaxaca in Mexico.

² Genoveva Flores Quintero, ‘Tequio, identidad y comunicación entre migrantes oaxaqueños’, Amérique Latine Histoire et Mémoire. Les Cahiers ALHIM, 8 (2004).

³Sebastián Rivera Mir, ‘Las monografías, o la historia en fragmentos’. Lecture at El Colegio de México (2010).