Tang Fu Kuen: How did you arrive at calling yourself an artist?

Elia Nurvista: I failed to gain admission into the state universities in Yogyakarta to read English literature and communications, so I moved to art school to pursue design. I then joined an all-girl collective, producing crafts that addressed gender issues. But I quit at this moment in 2010, when the local arts community peaked in its creative output and market fever, as I questioned the notion of ‘artistic engagement’. Through meeting and participating in Kunci, a discursive and archive platform operated by researchers, and scholars I became critically aware of research as a tool and methodology in artistic thinking and creation.

When I finally got my own kitchen, I happily experimented with cooking at home, often following the recipe blogs of Indonesian expatriate housewives living abroad. Through discovering food preparation as a ritual of communication between self and others – and as an instrument for both healing and inventing identity – I felt inspired to study food as my core artistic practice.

TFK: Can you share how your practice then developed?

EN: Holding on to ‘research’ and ‘engagement’ as principles, I was fortunate to be accepted into residencies abroad to form and test my projects. At Koganecho in Yokohama, I tried casual lunch sessions involving the exchange of family memories and recording them through fabric sewing. After that, back in Indonesia, I embarked on a few projects that questioned food politics, such as the production of foreign-imported foods in relation to local authenticity, the changing class consumption and gentrification processes. I also started looking at performative role-reversals during workshop contexts to upturn the power-functions behind food making and its target markets.

As I started to travel more, to Australia, Taiwan, the UK and Germany, I was led to examining food histories found in living and past migration. I found my world experience through understanding the stories behind definitions of ‘individual’, ‘home’, ‘mobility’, ‘community’ and ‘nation’. Above all, I could see the repetition of power imbalance, loss of rights, and continuing injustice.

In one of Kunci’s regular reading sessions in 2013, I came across Claire Bishop’s book ‘Artificial Hells’ where her arguments on ‘participation’ prompted me to consider a more critical position on audience action and witnessing. I am motivated to find ways to make the social relations and stakes in my food projects reach ‘thick description’, a term which the famous anthropologist Clifford Geertz developed while studying the layers of ‘social power performance’ during Balinese cockfighting rituals. I am increasingly convinced that my projects should not serve the ‘resolution’ of social drama; instead, they are situations in which many contradictory and ambiguous positions can be presented and discussed. Finally, I think ‘self-reflexivity’ is a state which makes everybody aware of the rules of the game, and that change is possible through performance.

TFK: Can you tell us a bit more about ‘Hunger, Inc.’, the project for which you are nominated for the 2017 Visible Award?

EN: ‘Hunger, Inc.’ was first presented in Jogja Biennale Equator XIII under the theme ‘Hacking Conflict’.

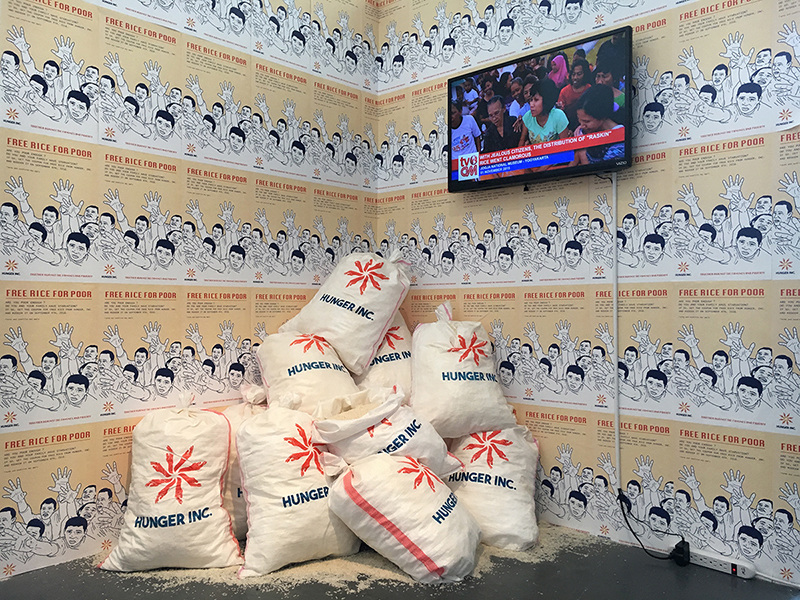

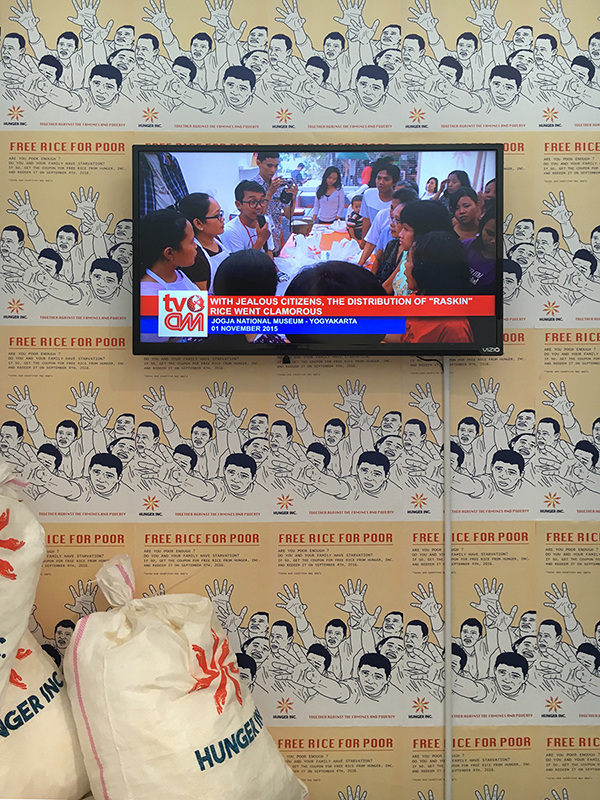

Framed as an institution, ‘Hunger, Inc.’ addresses the issue of food and its relation to the socio-economic and political hierarchies within the context of urban Indonesia. The installation set-up is that of an emergency tent with a big logo – a parody of makeshift NGO tents erected to help people recover from disasters. This tent is equipped with a community kitchen, a community dining table, a TV-which broadcasts news of riots related to the distribution of rice aid and also rice sacks containing poor quality and moldy rice.

‘Hunger, Inc.’ aims to look deeper into the spectrum of poverty – from mental aspects to structural problems of the society. Rice is more than just a staple food in Indonesia; it is linked to political economy in the country. In the ’80s, the Indonesian regime started to socialize rice as the main and only staple food, followed by an ambitious program called the Green Revolution. Rice has also been used as a political tool. One example is the RASKIN program, a subsidized rice program for low-income households, which often led to conflicts. From the bad quality of moldy rice and corruption among bureaucrats to the exclusion and inclusion of receiver households, the horizontal conflicts have sharpened greatly.

As an aesthetic intervention, ‘Hunger, Inc.’ invited the gathering of the poor residents near the riverbanks, and actively involved them in a series of events, including re-constructing the episode of the crowd fighting for rice. The scenes of RASKIN distributions that are broadcast on TV news have inspired these enactments. This performance was carried out by a voluntary group of frustrated commoners who have been struggling with this issue. They re-enacted their everyday roles within a performative context. Through this performance, we sought to bring the media images into real life as a form of catharsis. Subsequently, we created ‘Raskin Gourmet’, a travesty of fine-dining dinner experience, using bad quality RASKIN rice as the main ingredient cooked by a professional chef. Later, we also conducted a series of events, such as film screenings about food from trash; a cooking forum on rice for elementary school students; a parody on the tendency of local NGOs to ‘sell poverty’ in order gain funds from international aid agencies; as well as several dialogues on food commodities with a long history of colonial power and economic reforms, such as sugar, coffee, spices, palm oil, and instant noodles.

‘Hunger, Inc.’ is a way to build a long-term institution that focuses on reflecting, discussing, building discursive strategy, and strengthening solidarity among people who live in a precarious condition. Through several activities linked to food sovereignty, this institution is aimed at creating several experiments and speculations around autonomous solutions on the problem of poverty.