School of Engaged Art is inspired by a Brechtian perspective on the educational model as a practice to organize new forms of collectivity. It is thought as a privileged space where the dialectic between teaching and learning is a constant negotiation based on mutual trust and delight. Chto Delat (Dmitry Vilensky, Olga Tsaplya Egorova, Nina Gasteva and Nikolay Oleynikov) created the Curriculum together with all the participants of Chto Delat collective and all the present, former and future participants of the School.

Martina Angelotti: What’s the relationship between the School of Engaged Art and the Academies of Fine Arts in Russia?

Dmitry Vilensky: There is no relation. The academy is completely outside of any forms of contemporary art and holds an aggressive conservative position.

MA: Considering the research and the motivations on which Chto Delat is based, it’s quite easy to understand the reasons behind the birth of the school. But, to be more precise, what was the purpose that generated this project?

DV: I think that the school as we understand it is a community, which builds tools and art to provide a wider platform. At the same time, when we make a concrete proposal to politicize art, we arrive at the core of the issue and investigate what art and politics could be, what kind of community we need, and what kind of transformation of society we envision.

Nikolay Oleynikov: Right – the reason to make a school (as for the formation of our group Chto Delat in 2003) was to get together with an objective and in response to an emergency. We started this project after years of experiments with pedagogies and when the political movement of intelligentsia in Russia significantly shrank (failed) after 3-4 years of gradual inclination in engagement and presence (2011-2012 were the peak years in our recent history when thousands of citizens – mostly from metropolises – got involved in politics: e.g. Occupy Movement, Citizens for Honest Elections and so on). Friends, lovers, and sisters in arms were again eager to explore some (un)certain politics and pedagogies. We were also trying to reach out to the next generation of active and conscious people and to together form a platform for mutual learning.

MA: And which are the urgencies on which the program is based, also in terms of education and art production?

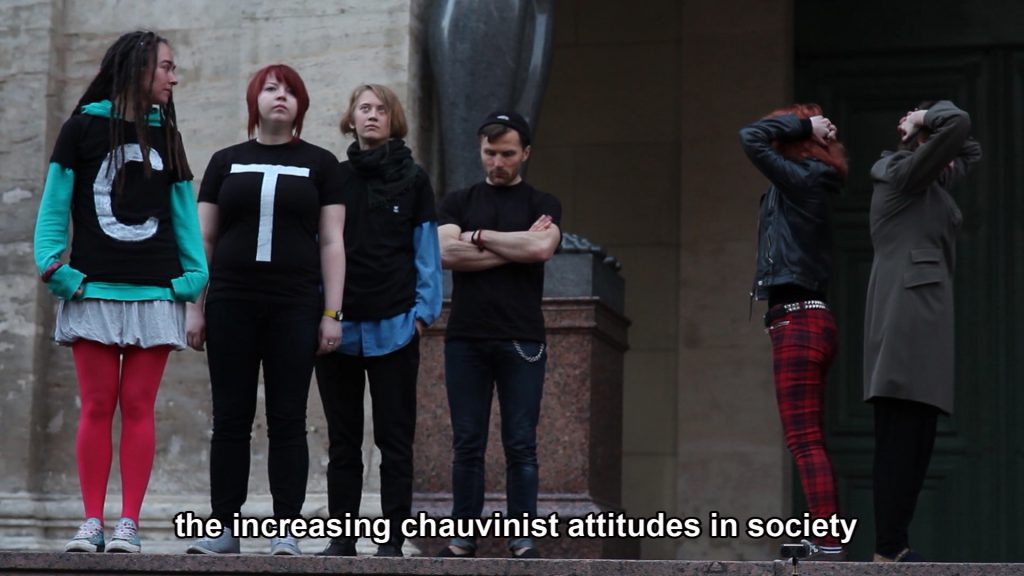

DV: In Russia we certainly have to compensate for a lack of general knowledge and practice of inclusive democratic process in society. We try and build new forms of political autonomy out of subjugation to the conservative status quo. And we treat art as a method to address things which are excluded from the public debate, repressed and marginalized. This is very urgent in Russia. At the same time the cross-disciplinary approach we use is pretty unique: we declare that as “We need a hybrid of poetry and sociology, choreography and street activism, political economy and the sublime, art history and militant research, gender and queer experimentation with dramaturgy, the struggle for the rights of cultural workers with the “romantic” vision of art as a mission”. So we try to transform our weakness (the lack of a proper institutional framework and the fact we live inside a rather oppressive society) into the power of experimenting with issues which are never properly studied in a normalized academic process.

MA: How can those urgencies reverberate and reflect in a more general context, out of the school?

DV: The school is located at Roza’s House of Culture which is a place where different activists and cultural initiatives have a place. You can call it a dissident or counter space. At the same time, it is a welcoming place inviting many people to come by and engage in activities which can hardly be found in other places in the area.

MA: Why should young people undertake this path, instead of the traditional one?

DV: I cannot say if they should or not – we are talking of a relatively small community and numbers. We cannot give them a practical base (like teaching how to make a proper career or money – in Russia there is no institution to support the art we make), rather, we involve them in a risky way of living. They know that police can raid the school at any moment for a heap of reasons (LGBT propaganda, anti-war in the Ukraine issue, a harbour of leftist extremists, a place where suspicious books and zines are distributed, a place where many illegal actions were prepared and so on).

NO: The very term “tradition” is very tricky, though it is at the centre of our studies and pedagogies. Since we are following a certain path of experimental, politically grounded practices and pedagogies of liberation, we admit that our school sometimes develops this confusion, and we have made ourselves ready to deal with it. We invite our participants to dip into the adventure of a hard-core, old-school engagement of artists into daily life, grassroots politics, and so on. Our challenge here is that now in Russia almost no one speaks this language anymore, so in a way we impose a situation in which a squad of dinosaurs calls for a herd of mammals to teach them some techniques to survive against the frost, and then they find a lot of interesting things to study in return.

MA: Do you think it would make sense to try and find another word to replace the word “school” in order to define this project?

DV: We like the word school. And it is a school.

NO: Though, there is a certain verbal detournement. Of course, our school does not have anything to do with the frontal oppressive system of schooling (we realize that schools in general were and are used to establish certain values of the ruling system), but we seriously take education as a tool of liberation, and school as a vessel for transformation. And together with our participants, we try to experiment to find new forms for it.

Olga Tsaplya Egorova: It is also a kind of school where the roles of tutors and students are rather interchangeable and this process is very performative in its nature.

MA: In the magazine published in the frame of the 7th Creative Time Summit in Venice, in 2013 (that was in fact titled Curriculum), I read an interesting text by Olga, that addressed the question of what you are expected to learn from the school. In the article, she shares an anecdote regarding her strong passion for jellyfish. Here you speak about the school as a “collective performance” which I found really appropriate. Would you tell me which are the methods you use in order to give shape to this performance collectively?

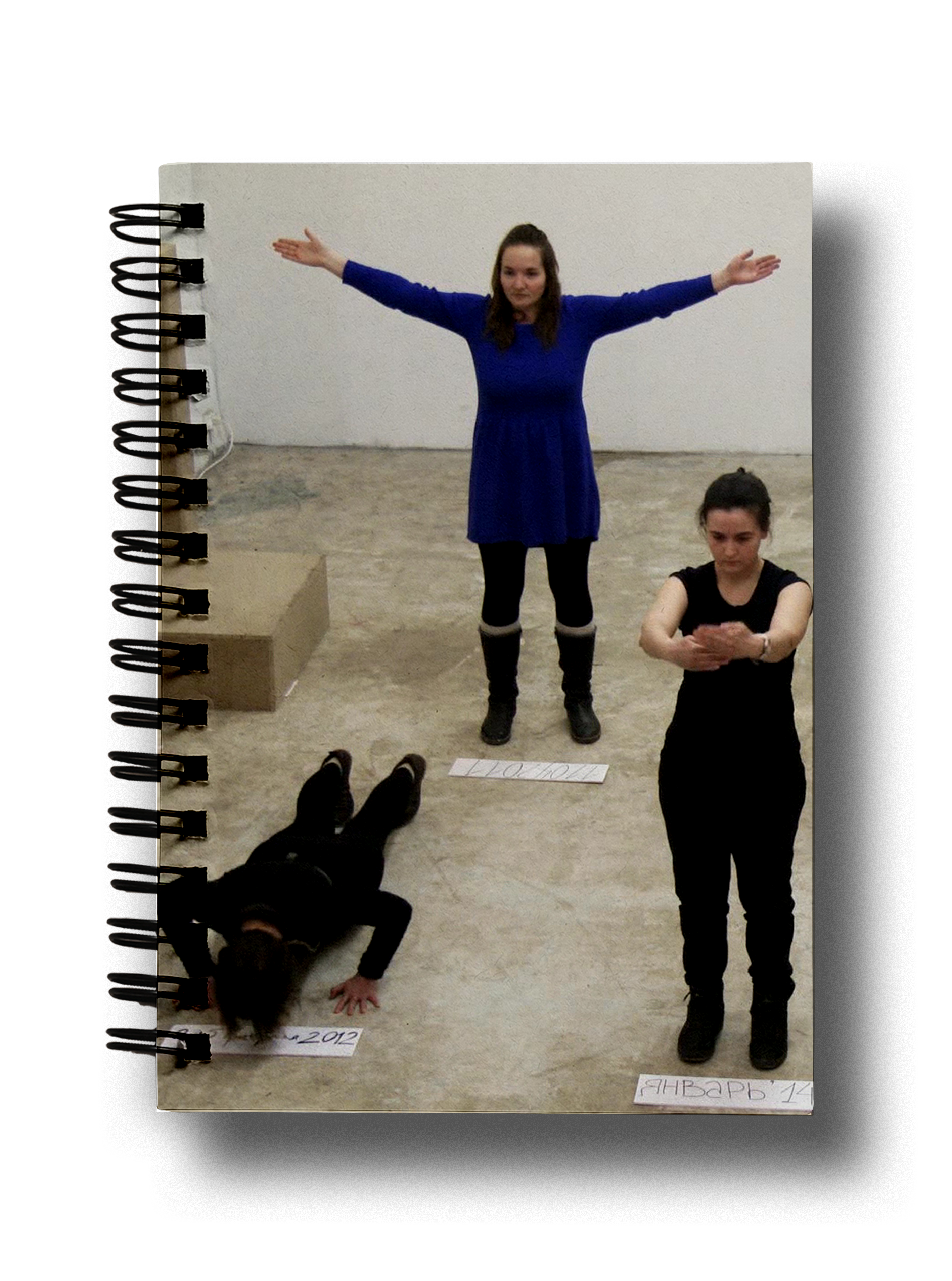

TOE: The school activity is shaped by body practices led by Nina Gasteva. This practice influences the relations between participants and helps them to recognize a space in between – exactly where performance and politics begins. Also, we deal a lot with narrative structures and create learning plays together.

MA: Who are the new “students” today in Russia and what can art education do for their empowerment?

DV: They are hungry in a direct and in a metaphorical way. And I hope that they can find a place unlike anything around and they have a chance to make it their own. This is important to get a place where you can be yourself and experiment with who you are in a community of similar minded people.

NO: Quite the opposite, I would say, School for our participant as it is for us is a battlefield. Blood, saliva, and lymph are constantly spilled, nurturing the sand of the arena.

MA: Which Russian or international models of radical education does this process of knowledge take inspiration from?

DV: We are definitely inspired by UNOVIS, Black Mountain College and confidential circles of Soviet dissidents.

NO: Besides these obvious historical examples we would also love to name our sisters all over the world, Ivan Illich’s institutions heritage- CIDOC in Cuernavaca, Mexico or Paulo Freire’s springs or Augusto Boal’s methods, or the heaps of autonomous zones all over the world from Ghana to Bahia, from Johannesburg’s Keleketla!, Library to Wood Land School in Vancouver that are giving us examples of resistance and structure. We also have sister pedagogical projects with which we constantly exchange tools and practices, from Kyiv, Ukraine, Minsk, Belarus, Lecce in Italy. Or sharing comradeship as with international pedagogical collective such as Ultra Red.

MA: Are you also thinking to activate the school in other countries?

DV: From time to time we develop international summer schools and learning plays abroad. Should we do it more?

MA: Yes, I think it would be really interesting to understand the process of development in order to enlarge methods of investigation and education which are not the same in every political and social context around the world.

NO: Here I’d love to add that before we launched our School in 2013 we were already experimenting with pedagogies. For more than 10 years we’ve been making a series, 48-hours of communal-living seminars, in Russia and abroad based on the protocols of sharing experiences and knowledge as well as the daily life. During these seminars we addressed the politics of today and continued our search for the forms of its representation

MA: Let’s talk about some practical information related to the school. How long is the education process for the students and what is the balance between the theoretical and the practical dimension in the school?

DV: It is a one-year course (2 semesters) and it is a balance (50-50) between theory and practice. May be more practice which is not studio based work – we have a strong focus on body practices and the use of public space.

NO: In fact, the balance we try to achieve goes further. We also have invited 50% of local participants, who are based in St-Petersburg and the other half from all over Russia and former Soviet Republics. That balance also brings a very important pedagogical element of the mutual, deeper and constant exchange and sharing of local struggles, creating new networks of solidarities. That is a very practical element that is extremely important to mention. In our school artists and activists from Ukraine, Kyrgyzstan and Belarus meet with their comrades from Moscow, Omsk, and Berlin and create their engaged (and engaging) projects beyond the school’s frameworks.

BUTAND we consider theory as one of the important practice. And other participants of the Chto Delat group lead their programs in Philosophy (Oxana Timofeeva, philosopher, Chto Delat), Aesthetics (Artemy Magun, philosopher, scholar in political science, Chto Delat), Critical Writing (Alexander Skidan, poet, literary critique, publicist, Chto Delat). Also some activists and researchers are leading their inquiries in feminist and queer politics (Alla Mitrofanova), history of modernisms (Andrei Fomenko). Andor – very pragmatic practical master-classes in puppet theatre and theatrical prop making (Aliona Petit), or rally prop making for the May 1st rally (see the Art as Social Action by Gregory Scholette), and practical participation in political events.

MA: Is the school free of charge for students?

DV and NO (imitating a choir singing): It is free and we provide travel grants and we cover accommodation for those of our participants who are not based in St-Petersburg and free lunches for everyone. We work in a module structure – 1 week per month to stay and study intensively together. Then all come back home with heavy homework duties. To get prepared for the new block of commonly shared studies.***

***Peculiar detail (less about sustainability more about pedagogies): each new block of studies is usually based on the topic that the participants study between the blocks. But they always come back to the School with a lot of practical work done: video reports, short stories, critical essays and so on are the shared basis to inform, deepen and broaden each next step of investigation at the School of Engaged Art. Most of the homework is being delivered with a goal to form micro collectives in order to practice Art and Engagement.

MA: Apart from the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation, are there other funds supporting the educational program?

DV: The school’s major support till now is RLS Moscow (90%) and about 10% comes from our own Chto Delat mutual aid fund.

MA: How are you going to use this award in case you win it?

NO: As the political situation in Russia now dictates instability for all the projects supported by any kind of foreign NGO’s (see the foreign agent– and undesired organizations – recently applied laws) – the School of Engaged Art’s future is more than uncertain. This award would help us to create a more stable and sustainable ground and buy us some more precious time to co-create a visible community of activists, artists, thinkers and doers in our town and beyond. To empower practical connection of young (not in terms of their physical age, as we have people involved as participants to our School from -20 to 50+ y/o) generation who will be engaged with art and will engage art as a life-changing experience in their now and tomorrow practices and engagements.