Generally, we associate the word ‘school’ to the idea of a very specific space. Instead, Visible program’s #On Pedagogy underlined a shift of this perception, inviting artists who enacted new pedagogical models intended as nomadic types of initiatives.

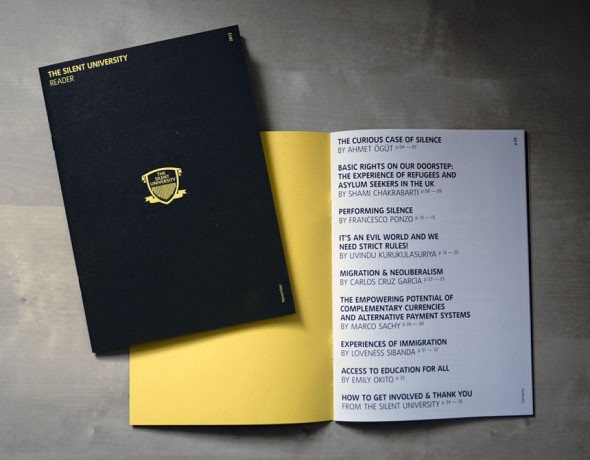

The program consisted not only of talks and discussions but also the presentation of the Silent University orientation module, where texts, books, and films were made available to the public. One of the Silent University’s principles and demands states that the school should sustain a ‘decentralized, participatory, horizontal and autonomous modality of education, instead of centralized, authoritarian, oppressive and compulsory education’. This notion is sustained also by Jacques Rancière in his book The Ignorant Schoolmaster (1987), where he argued that schools should rethink the idea of pedagogy. Instead of denoting a passage from the unknown to the known and from those who possess the knowledge to those who don’t, pedagogy should look at how all forms of ignorance are also conditions of knowledge. Another aspect worth mentioning is the importance of a collective approach, fostered by all the schools presented during the program, as well as the effort to include people and users that don’t normally have a voice in these environments.

Connected to the idea of reproducing new pedagogical models initiated by artists, the concept of space becomes more flexible. The stress caused by the physical space of learning was central for Pascal Gielen, director of the research center Arts in Society at the Groningen University and guest of the third session.

Gielen, during his presentation, explained how schools often transform their spaces to be more productive. As a result, students and teachers are usually asked to deliver a final product, which is very far from the idea of ‘mis-measurement’ often associated to art schools, which clearly need a certain amount of freedom to experiment. To demonstrate his thesis he showed some examples of changes in education policies in relation to the transformation of educational spaces.

All of the artists invited to present their new pedagogical models are implementing new forms of education that could be grouped under the idea of nomadic and temporary institutions. Providing knowledge, but also ‘free time’ in an unconventional way, where the most relevant characteristic is represented by the emergence of human relationships that cannot be sold.

While discussing the various school models invited during the program, some questions arose such as: who has the right to schools? Could these examples become models for different organizational structures?

Even if every project refers to a clear target group such as asylum seekers, illiterates, stateless people as well as art students, they denote how more and more artists claim the importance of their role in discussing fundamental rights in our contemporary world.

Artists working on implementing pedagogic models via their artworks are like secret agents in the real world with an artistic agenda in mind (1). They create projects with a double ontology, which is putting a certain pressure not only on the participation but even more on the spectatorship. The so-called ‘secondary audience’ becomes relevant when artists have to represent their projects in an exhibition context. The spectator’s presence is relevant because it demonstrates that there is always someone that can learn something from the projects, not only contributors in the moment of the action itself. Having both participants and an audience in fact, pushes projects to be successful in multiple contexts, testing the conditions we apply to several domains (politics, art, pedagogy, etc.). Essentially such activities open up the frequently asked question of whether these artworks belong to the field of art at all. Socially engaged art, in general, does not fit into the traditional art market dynamic and at the same time abolishes the idea of the artist as individual, because it is a collective process in nearly every case. Going back to the relation between art and pedagogy, the permeability between the two disciplines is still a space of ambiguity because the temporary trespassing of art into pedagogy and vice versa brings new insights to a particular condition and in turn makes it visible to other disciplines (2).

More than other fields considered by social practices, education is a process of social exchange accepted with mutual trust and commitment, which lasts years. It pushes artists to give a structure and narrative to the almost invisible exchange between students and themselves.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights Art.26 states that ‘education shall be directed to the full development of the human personality and to the strengthening of respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms. It shall promote understanding, tolerance, and friendship among all nations, racial or religious groups, and shall further the activities of the United Nations for the maintenance of peace.’ I think that the new pedagogical models that are being developed by artists are a perfect example of how to promote education. Implementing and spreading these new initiatives in the near future is key if we want to achieve social change through art.

(1) See Por un arte clandestino, Pablo Helguera in conversation with Stephen Wright

(2) Pablo Helguera, Education for socially engaged art, Jorge Pinto Books, 2011