Like one of her early role models, the American performance artist Suzanne Lacy, Jasmeen Patheja’s art engages with diverse communities about important social issues such as violence and its links with fear. Like Lacy, all of Patheja’s work—from the early interventions confronting street harassment to the ongoing, ambitious I Never Ask For It—centres around listening and being heard.

‘As an art student I would question where art lies beyond a gallery. Who builds art? Can art heal? Can it be confrontational?’ says Patheja. Over nearly two decades, through her organisation Blank Noise and the labour, love and generosity of its community of action Sheroes/Heroes/Theyroes, she found the answers to these questions. The result is a unique movement facilitated by conversations, installations and street interventions that resonate with thousands; one that adeptly balances intimacy and scale.

Who says you can’t be inspired by the patriarchy, especially the corrosive Indian version of it? To truly appreciate the importance of Patheja’s work—which she started as part of her graduation project in 2003 and ran as a community-led collective until 2015 when it was registered as a trust—it is key to understand some basic truths about the monster she is up against.

According to the National Crime Records Bureau, in 2010 more than 97 percent of Indian women are abused by men they know. Marital rape is not illegal in India. The preference for boys over girls and the country’s ugly, decades-long history of sex determination and female foeticide which unbalanced the sex ratio at birth has resulted in a unique modern-day dystopia. North Indian men often travel thousands of miles in a desperate search for a bride.

Women’s electoral issues in the testosterone-driven world of Indian politics are restricted to multiple versions of one narrative: the state as protector. A few years ago, a former state law minister reassured citizens that beautiful women would be able to go out in the city at night if his party was given charge of the capital’s police force. A key bill that will ensure greater representation of women in parliament has been delayed for years.

India ranked third lowest in the world on health and survival in the annual World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Index in 2018. Our hourly wages gender gap was the highest among seventy-three countries featured in the International Labour Organisation’s 2018 report.

Indian women are dropping out of the workforce at an alarming rate. A jobs survey released in early 2019 found that only 23.3 percent of women above the age of fifteen were in the workforce, down from 42.7 percent around twelve years ago. Sexual harassment at the workplace is a key reason for this steady decline.

Against this bleak canvas of a deeply misogynistic society is the problematic way in which we bring up our children. Women’s oppression starts early, insidiously, within their families, says social scientist Deepa Narayan in her book Chup: Breaking the Silence About India’s Women.

Narayan chronicles the different tools used to perpetuate this everyday violence. She says girls are taught to feel shame about their bodies and disguise them; to be voiceless, just listen and follow, don’t answer back; to please and serve others, smile but not laugh; to deny their sexuality and sexual safety; to keep apart from other women and to be afraid; that duty always trumps desire. Imagine how weighted down women are by the time they enter adulthood.

Patheja’s first encounter with the patriarchy was a story she heard even before she attained puberty. ‘I was told about a girl who fell in love with a Muslim man and how he took her to the Middle East and sold her. The narrative of blame was introduced early,’ she recalls.

‘She became a prostitute,’ Patheja was told when she worriedly inquired what happened to the girl. ‘Her parents declared her dead and performed a puja (prayer) to mark her death.’

It was only later—after listening to countless narratives that Patheja understood an important truth: we are all survivors. The purpose of that early story was to let her know what was forbidden—agency, love and the consequences of following one’s dream.

When violence occurs, blame is most often firmly attached to the woman. Blame and fear shadow a woman wherever she goes, from the workplace to the streets to her home. Women are brought up on a steady dose of ‘if you do this, then that will happen’. Incandescent safety warnings have dotted our environment for as long as we can remember. Every woman is well acquainted with these two emotions and has already internalised them in her formative years thanks to her family. ‘As a result,’ says Patheja, ‘most experiences of sexual assault, violence, threat and intimidation have been silenced and untold.’

It was when the Blank Noise project was having these conversations in 2004 that Patheja noticed that women often referenced the clothes they were wearing when they had been assaulted.

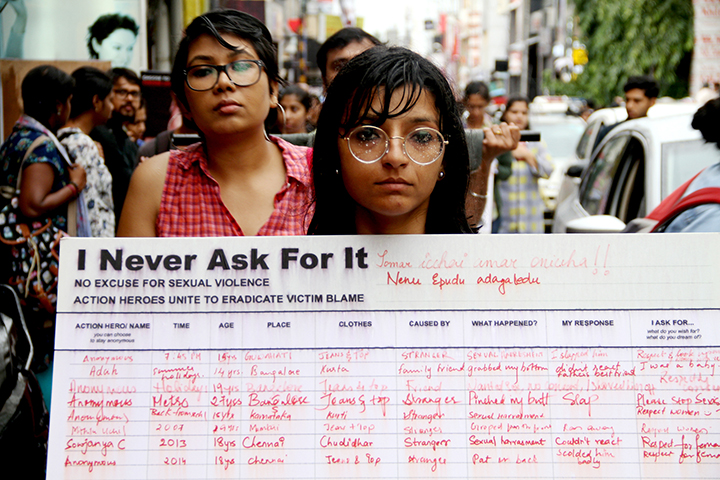

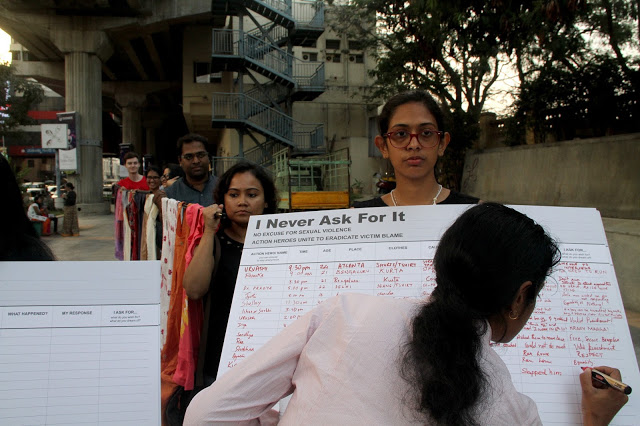

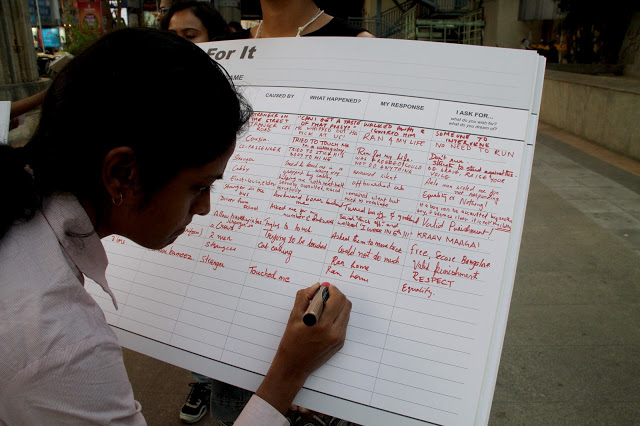

Many women could recall their outfit down to the tiniest detail and the idea of the clothes project, I Never Ask For It, was born, recognising the systemic use of blame across spaces of violence.

‘Each garment is witness, memory and voice to the survivors’ experience of sexual assault,’ says Patheja who wants to take ten thousand such garment stories to India Gate—a war memorial that doubles up as a site of protest and a space for largescale gatherings in the capital city—in 2023. Patheja believes the idea could be replicated in other parts of India and the world by action sheroes/heroes: ‘Along with audio testimonies, they could be housed in a space that will become a living museum to end violence against women in India.’ She believes that when we are free of blame, we will be free of fear.

Action Sheroes understand the deep relationship between violence, fear and blame. They are core to everything at Blank Noise. ‘As an artist/facilitator, I am listening in and facilitating the collective,’ Patheja says. ‘The ideas have no shape without those who participate. Action Sheroes are also more than participants, they step in and take agency. All ideas are inspired by the personal and collective lived experiences of self and members of the growing and open community.’

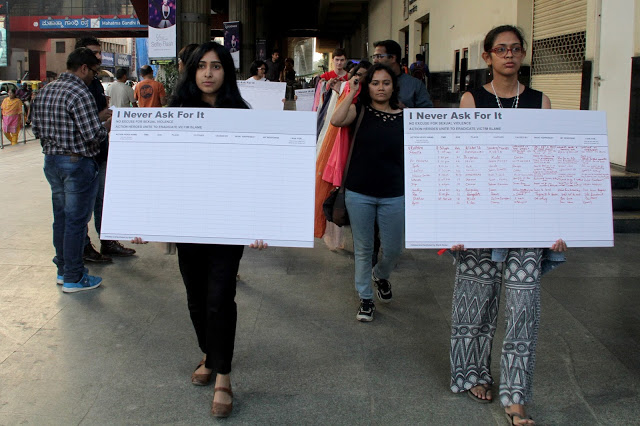

In I Never Ask For It, Action Sheroes carry an installation of garments and testimonial boards in a Walking Towards Healing march across the city; male onlookers might step in to help them as a symbolic gesture of shared responsibility. Workshops and listening circles inspired by the gestalt awareness practice of active listening help women to identify the weight of the blame and shame they have carried for so long. The solidarity they experience is cathartic.

Alongside I Never Ask For It, the collaborative research project Reporting To Remember archives news reports where blame is used to justify violence against women. Blank Noise reasons that when violence is justified it is perpetuated, and hence this is a pledge to not forget.

Patheja has never had any shortage of creative ideas from the time she encountered street harassment when she moved to a new city to attend art school. She realised that though many women experienced similar harassment, nobody talked about it. They didn’t want to shine the spotlight on their fear. Back then she noticed that women’s bags always contained everyday objects such as the ubiquitous safety pin, red chilli powder and cockroach spray that doubled up as weapons of defence (and thus was born the online Museum of Street Weapons of Defence). In Excuse Me? Compilation of Misdirected Terms she made lists of fruit names that women had been called, songs that had been sung to them and words that had been used to describe them.

A Step by Step Guide to Unapologetic Walking was a list of things to remember while walking—a demonstration that we were proud of our bodies and would inhabit public spaces uninhibitedly.

In 2012, Patheja taught a month-long course at her alma mater, Srishti School of Art Design and Technology, where she stayed on as artist in residence from the following year. Students talked about the ‘rapists’ lane’ in the neighbourhood. ‘Talk to Me was a response to the politics of fear and patriarchy. Which kind of man are we taught to fear? How fear is used as a tactic to control our mobility,’ Patheja explains. The first thing Action Sheroes did here was to rename it the ‘safest lane’ and not use vocabulary to perpetuate this story of fear.

Action Sheroes invited strangers to come talk to them about anything except sexual violence in an hour-long conversation that they hoped would initiate possible connections and mutual trust. ‘Could this dissipate the fear? Question the biases both sides held? That’s what we wanted to find out,’ Patheja says.

Another campaign, Meet to Sleep, mobilised women to take a nap in public parks. It reiterated a key theme at Blank Noise—to meet one’s inner fears head on and to become part of a movement towards creating a safe environment. Last year this took place in twenty-five places across India including at an abandoned airport in the north Indian town of Muzaffarpur and under trees in villages where there are no public parks. Blank Noise and the feminist collectives that drove this project found that many women continued to cluster together, feeling safety in numbers. Patheja and her band of Action Sheroes believe they have the right to trust strangers, the right to be free of fear and the right to walk under a starlit sky. Most importantly they stand up for the right of every woman to be Akeli Awaara Azaad (they put this line on a T-shirt, too): Her Own, Unapologetic and Free.