Luke Ching is an HK artist coming from a working-class family. In a conversation we had in preparation for today, he recalled how difficult it used to be when he was young and had to choose a present for his father’s birthday. He didn’t know what to give him because his father didn’t have any hobby or interest; he didn’t have the time, he just worked and worked long hours. So Luke took the decision that growing up he wouldn’t have followed his father’s steps and would have become an artist. Now, as an artist, he asks himself: when you are a worker, how do you keep your curiosity? How do you fight for your value as a person?

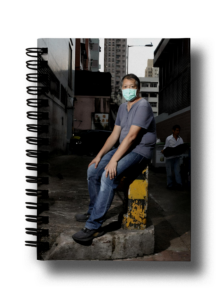

Observing the daily HK dynamic and talking with workers in various jobs, Luke started in 2007, twelve years ago, the Undercover Worker working in various jobs, including security guard, street cleaner, and cashier in supermarkets. In this way, he has the opportunity to experience first-hand some issues of that particular job. After this phase of “research”, he campaigns in favour of workers’ rights with different strategies, like writing in newspapers and using social media.

To understand the importance of the project it’s necessary to consider the context of Hong Kong. Reading the news, we have all become familiar, since last June, with the current protests that oppose the government’s proposal for a law that would make it possible for any person in Hong Kong to be extradited and face trial in China. But this is not the only issue in HK.

The biggest protest before the current one was in 2014, in which many areas of Hong Kong remained closed to traffic for 77 days because more than 100,000 HK citizens were protesting and trying to obtain universal suffrage. In fact, HK is not a democratic country. The political leader – (currently Carrie Lam) – is chosen by a committee of 1,200 people from pro-China elites.

I lived in HK for about one year between 2013 and 2014 and could see the emergence of those protests, called the Umbrella Revolution. I could also experience how Hong Kong, so attractive for being beautiful, shiny and luxurious is, though, also an extremely market-driven society and one of the most highly capitalised and dehumanised cities in the world. People not belonging to the higher social and economic classes might feel isolated and defenceless. The work sector is the main example of that. Collective agreements cover less than 1% of workers, and those that exist are not legally binding. Workers are subject to employers’ arbitrary actions, have no security, and no collective bargaining rights.

In this difficult context, Luke defines himself as an indicator: he observes what needs to be changed, fully immerses himself in the issue, and works on the daily reality, trying to achieve small but crucial changes.

How does Luke choose the jobs he will take?

Some of the jobs upon which he insists the most are security guard and cashier in shops. These are jobs in which usually people from lower social classes work. Luke also observed that a big part of these workers have specialisations and skills, but are forced to accept basic and modest positions because of the continuous and sudden economic changes in the Hong Kong economy.

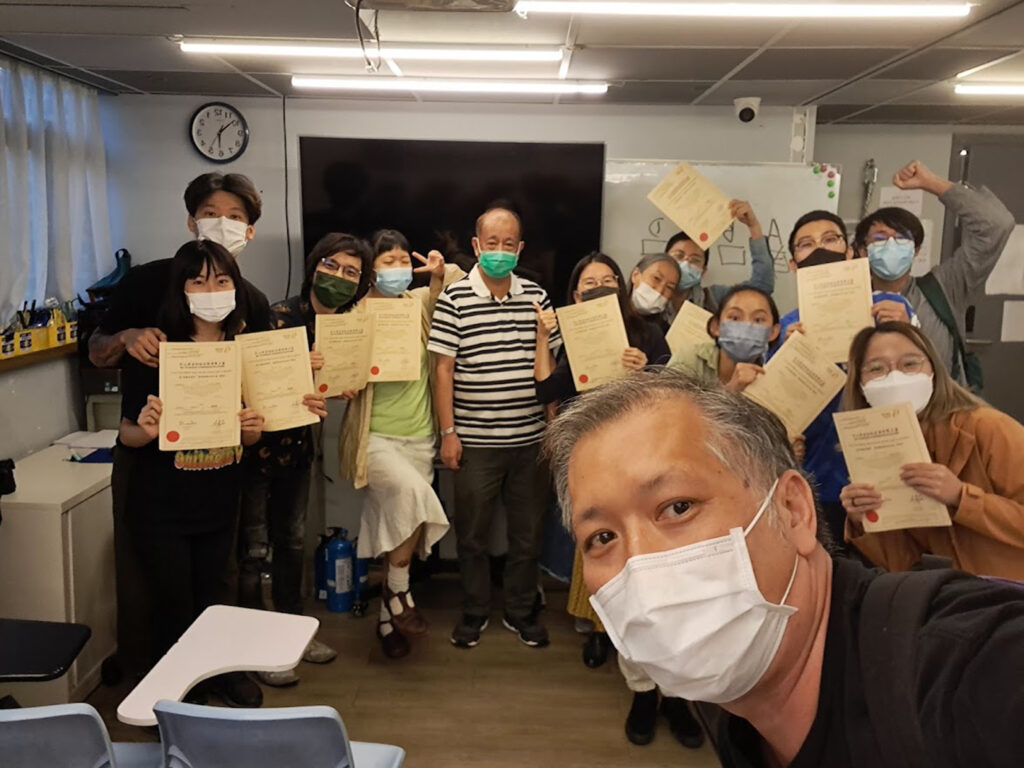

There are three recurrent elements in Luke’s practice: his first-hand experience of the jobs; the communication, which includes writing articles in newspapers and posting on social media; pushing to obtain real changes by dealing with labour unions, organisations and public bodies. Luke’s work has already changed the daily life of hundreds of workers because it changed the policy of more than 30 big companies. We are talking mostly about supermarkets, convenience stores and cinemas, but even about public institutions like the Hong Kong Art Museum.

What’s happening next?

At this stage of the project, Luke wants to involve others in the project. He already uses his Facebook online community as a tool to involve Hong Kong citizens. For example, he asks the group members to report situations in their own neighbourhood or working place and to actively voice their opinion when they notice something unfair. But, apart from that and some sporadic collaboration, he has in general carried on this work alone.

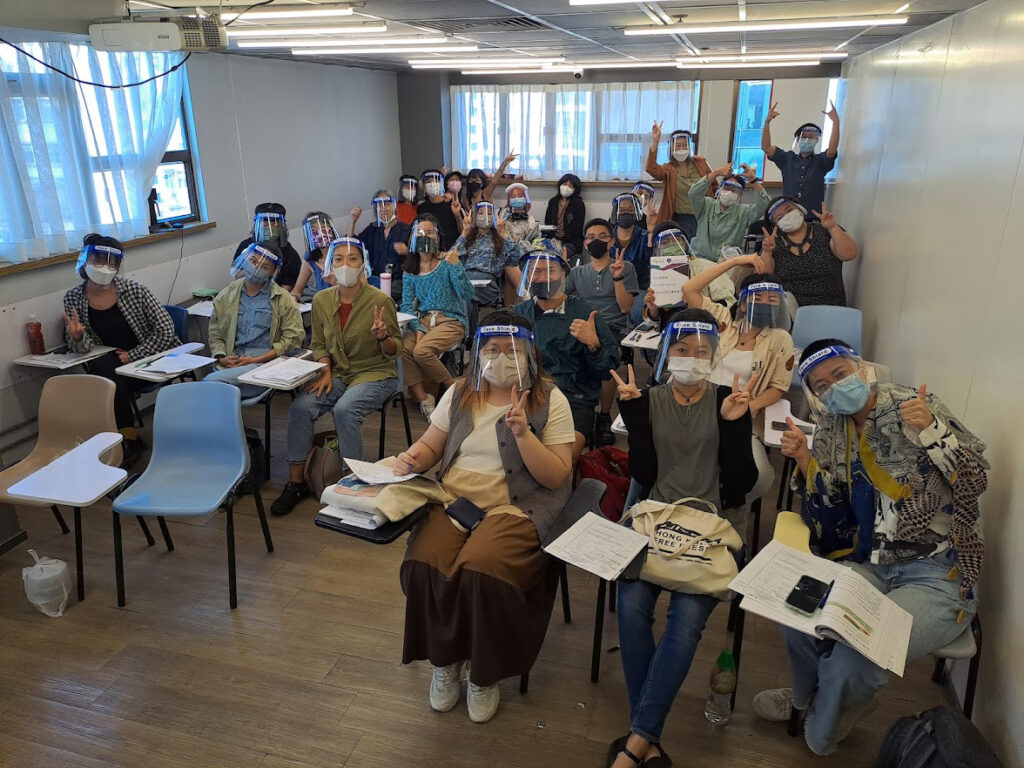

To open up this project, he feels that a big step forward is NOW needed: an internship programme for university students that places them as “undercover workers”. Students would have to empathise with workers from lower social-classes, experience that kind of daily life, and apply their critical thinking to the unfair HK social stratification. This step, that would be possible with the Visible Award, could truly change Hong Kong society, because if Luke Ching’s work alone already pushed forward changes in 30 companies, how much more could be done by tens – in the years, hundreds – of young people committed to a new vision of equality?