Martina Angelotti: You have just been awarded together with the Karrabing Film Collective the visible Award 2015. I was part of the public jury that day, and I can definitely say that it has been a great experience of common learning. Did you attend the streaming?

Elizabeth Povinelli: I was at the Belyuen Community, just across the Darwin Harbour in the Northern Territory of Australia where most Karrabing lives, shortly before the parliament met. For the most part, we were sorting out who did or didn’t have a birth certificate—a requirement to apply for an Australian passport—and also designing “Toxic Sovereignties #4, Mudibandjirrk Dreaming” for an exhibition at e-flux gallery in New York City. Judith Wielander and Matteo Lucchetti sent the official pamphlet for the Visible Award presentation that same week. Because I am the only Karrabing member with a passport at the moment, I left for Saskatoon, Canada, the day before the Liverpool parliament. E-flux and the Remai Modern were screening our Windjarrameru, the Stealing C*nt$ about Indigenous incarceration and multinational mining in the far north of Australia. During the parliamentary discussions I was sitting in Saskatoon, where First Nation people face a similar set of struggles with poverty, mining, and ongoing colonial appropriation, jumping in and out of the live-stream and the online summary and sending back summaries via Facebook to the other Karrabing members. The community doesn’t have any publically accessible wifi or any reliable telephone coverage. To get reception people stand on top of outdoor tables or roofs, or wedge their mobile phones into screen doors—no reception is a reoccurring theme in our film work. Everyone heard the good news when I called the day after. I agree that the parliament discussion was quite powerful. I found many strands of the conversation particularly probative for the Karrabing including the difference between self-defined “artists” and art; the, at times, awkward relationship between aesthetics and social urgency; the question of what counts as a political event across social contexts and life-worlds. Some members of the Karrabing come from a lineage of well-known performers and painters—some locally and regionally known, others nationally and internationally. But prior to beginning the film collective, no one in the group circulated in this world. And most Karrabing are, at this moment, less interested in making art then using film, media, and art as a means of altering the world —someone in the parliament put it quite nicely, film for the Karrabing is “an endeavor” to open a space for an otherwise within the current configuration of settler power.

MA: How do you feel now and what was the Karrabing’s reaction after knowing the response about the prize?

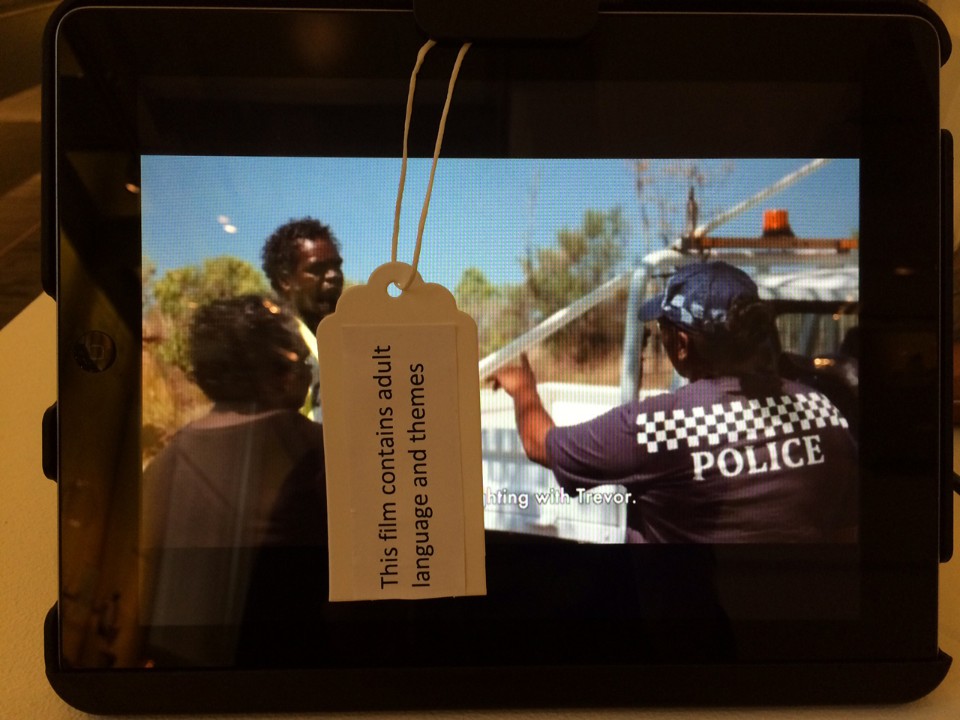

EP: I was twelve hours behind Australia. When I woke up I immediately called some of the other senior members of the collective: Sandra Yarrowin, Claude Holtze, Linda Yarrowin, Angelina Lewis, and Rex Sing. Sandra thought I was playing a joke on her (the Karrabing are big on playing jokes on each other). Linda and Rex told me to get back on the plane so that we could have a huge party. News then spread quickly as the younger kids raced to tell everyone on facebook. They were thrilled, but their feelings about the award had to compete with a recent suicide and a string of deaths in the family and when the Karrabing made a short video for the award presentation in New York City they were still in their funeral clothes. I mention this in order to note that part and parcel of the politics and aesthetics of Karrabing films are the constant disturbances that compose their everyday life. The life expectancy of the Karrabing are more than ten years below non-Indigenous Australians, the average income for Karrabing members hovers around AD$10,000 and indigenous people represent 3% of the national population but 28% of the prison population. In these contexts, politics and aesthetics cannot be unwound (take for instance the simple issue of continuity “errors” in our films, some inconsistency of clothing, cars, mobile phones, and even characters across scenes). What might appear to be aesthetic slippages are actually the aesthetic registers of Indigenous life in settler liberalism. Some people in earlier scenes are now in jail, so we shoot around that as well. We could insert extradiegetic footage but we think that allowing unavoidable inconsistencies to be a part of the visual field might be more powerful.

MA: Let’s try to go deeper in the project, which is quite complex not only in terms of structure but also in terms of feelings, practices, and topics it’s trying to outline. When did everything start and how did you get in touch with the Karrabing? Which is your role in the collective and how the collective itself is composed and organized?

EP: Most members of the Karrabing were born and raised on the Belyuen Community. I first went there in 1984 on a Watson Fellowship having received a BA in Philosophy in the US. Marjorie Knuckey, the Indigenous head of the Women’s Centre on the community, invited me to work for her writing grant applications. During this time the community was in the middle of a long-running and very contentious land claim. Australian federal law mandates that a lawyer and an anthropologist represent Indigenous groups lodging a land claim. At the end of my fellowship, the senior men and women asked if I would come back as their anthropologist. So I studied anthropology at Yale University and have traveled back and forth to Belyuen and its surrounds two to six times a year ever since. Most of the adult members of Karrabing were seven to twelve years old when I first arrived. So we’ve grown up together. But this doesn’t mean that we are treated the same. No matter how much we might love each other, experience ourselves as a family, argue, celebrate, and mourn together—states and public treat us very differently.

The Karrabing didn’t exist in 1984, or it existed only as a potentiality.

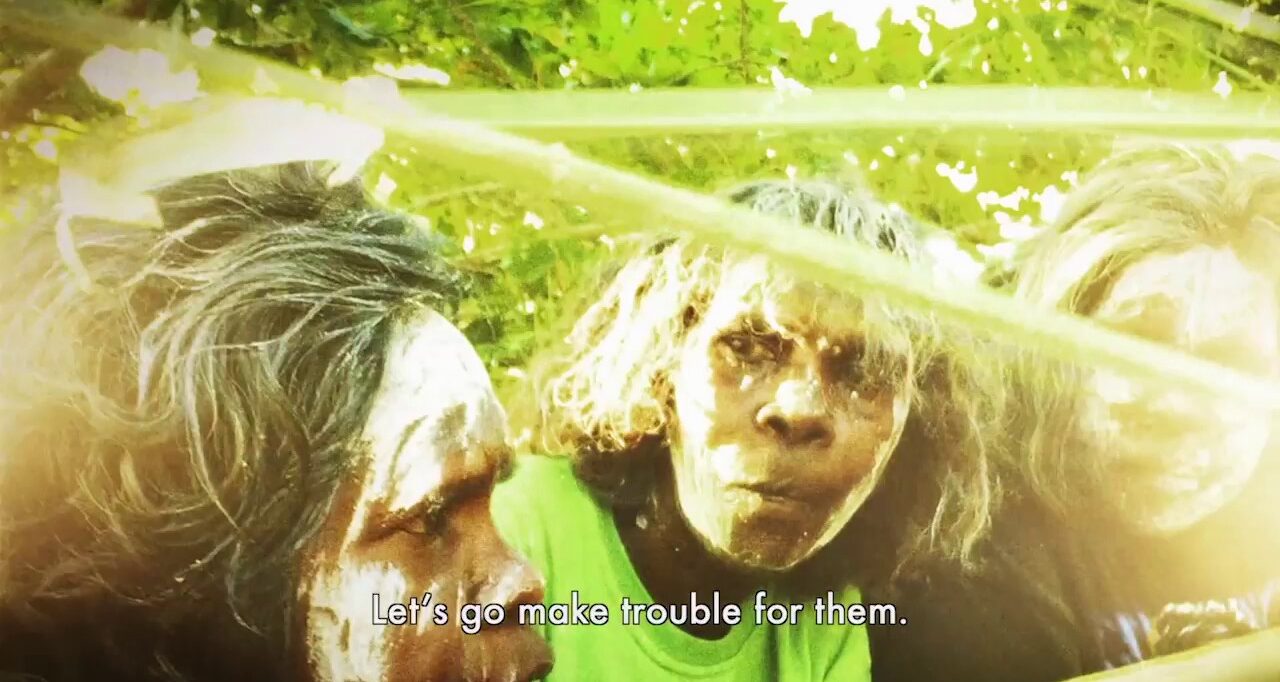

Karrabing is not a place or a people. Karrabing refers to the state when the vast coastal tides are at their lowest and is contrasted to karrakal, when the tides at their highest. What existed in 1984 were a group of interrelated families who had been interned on the Belyuen Community in the 1940s. The Australian government shifted course in the late 1970s from Indigenous assimilation to so-called Indigenous self-determination. Land claim hearings and cultural heritage protection were heralded as the cornerstone of this new era of social justice. But, in fact, land claim legislation divided Indigenous communities on the basis of anthropological theories about traditional authenticity, rather than supporting local desires and imaginaries. Perhaps not surprisingly then, when the last of the elders died in 2007, Belyuen was torn by a riot. In the beginning, the government promised to build housing for them in their traditional country, but then the Intervention hit—a federal assault on Indigenous rights on the basis of a sex panic—and they were abandoned in the bush.

One evening, the discussion turned to how to remake their lives in this state of abandonment. Who were they as a group? What should they call themselves? No one wanted to use state-mediated anthropological concepts to make sense of themselves—they refused to divide themselves on the basis of this or that tribe, this or that territory, this or that clan group. No one quite remembers who first came up with the idea of using the name karrabing. But whoever did the idea immediately stuck—it articulated the field of actual differences into the unity that was potentially there. The Karrabing Indigenous Corporation—the film collective is one of its projects; we have also created a series of installations that accompany film screenings—stipulates that only 10% of the group can be non-Indigenous and non-Indigenous members “must contribute tangible assets and assistance.” This includes me.

MA: In the video presentation the Karrabing Film Collective made for the Visible Award, I found the use of IMPROVISATIONAL REALISM a perfect term to focus on their practice. Actually, the films you created could be considered more as a re-enactment or reality than as a non-documentary choice. And the definition itself evokes to me a FACTIONAL dimension, a mix between fiction and fact. Can you tell me which is your meaning of improvisational realism? And of which kind of “realism” are we talking about?

EP: I like factional. Realism is a term of art. Even in strict documentary approaches the desire to present a unmediated reality, whether through authentic footage of an event or a truthful reenactment, is mediated by frame, edit, sound, projection etc. So improvisational realism is hardly about representing unmediated reality for the Karrabing anymore than any other media group.

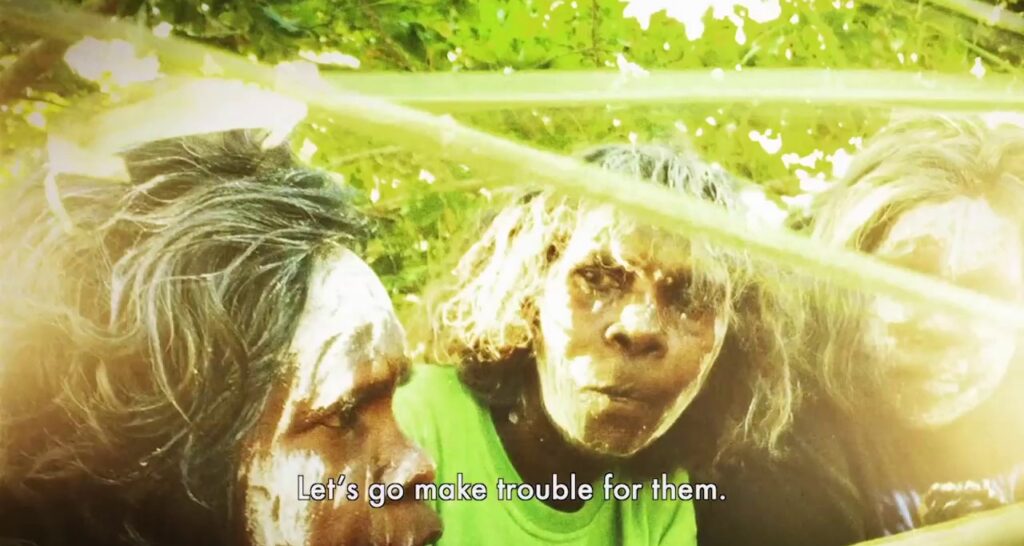

It is an aesthetics that carries over from the Karrabing’s everyday strategies of living in settler liberalism, where a large gap opens between the resources one has and what needs to get done with them and where almost no space exists between the multiple realities that constitute everyday life. The plots of the films are for the most part worked out before shooting starts, but the dialogue and blocking of scenes are improvised while we are shooting. Sometimes the plot shifts too.

But improvisation doesn’t merely refer to a performative style, It also articulates as an artistic style to an art of living. One of the reasons we’re shooting Wutharr with iphones is to intervene in typical production schedules to see if the compact durability nature of these phones along with a compact sound kit articulate with the lived nature of improvisational realism.

MA: Let’s jump to the concept of “making films”. How do the Karrabing work together, how do they choose the stories in order to shape what it is to be indigenous today? Is it conceived as a practice of mutual understanding in acting out real life?

EP: Karrabing don’t operate on a model of together or separate, mutual or divided, but together and separate, mutual and disagreeing. Indeed, the arguments about which way of doing things is best and most beautiful are indexes of the continuing relevance of these things to the Karrabing. People argue because they have a stake in the outcome—but they don’t abandon each other if their way is diverted.

The composition of stories reflects this, I think. Someone in the group suggests a fairly simple plot. Over time, if the idea sticks, others add characters and subplots until the arch of the film emerges. Some of these conversations happen in formal meetings but most of the story composition happens on porches or the side of a road or in grocery stores. Scene locations are selected—but because everyone knows the country inside out the scene are in crucial ways already organizing the plot. I am charged with pulling together crew or in this case iPhone 6s.

And, everyone decides what part she is willing to play. When we first started, Karrabing members wanted to concentrate on acting and to pull into the process, professional filmmakers and cinematographers. I asked my friend Liza Johnson if she’d workshop the story with us as a collective, and codirect our first film, Karrabing: Low Tide Turning. I was charged with managing the editing and worked with David Barker who then came to Belyuen for our second major work, Windjarrameru, The Stealing C*nt$. We also worked with Ian Jones on When the Dogs Talked and Windjarrameru. We are experimenting with credits—seeing credits as a space for modeling a performance ethics and aesthetics.

MA: Part of your references are two cultural strong movements, the Third Cinema and the Theatre of Oppressed. How do you translate those two dimensions, socially and practically, in the films you conceive?

EP: Rex Edmunds, Linda Yarrowin and I were doing a radio interview on Triple R during the Melbourne Film Festival. A question arose: “Why film?” Rex said he liked how, in acting out scenes pulled from his ordinary life, he could see his life more clearly. And as the films traveled into other Indigenous and non-Indigenous spaces the process could be reversed. Obviously, this spect-acting was put to use in the Theater of the Oppressed. Unlike the Theater of the Oppressed, but like Karrabing films, Third Cinema can be rewound and replayed. Moreover, our films speak to the nature of colonialism although, as hopefully is now clear, our film collective emerged out of a revolt against the way that they were being governed rather than being inspired to revolt by a film.

But the interviewers were also looking for an aesthetic answer. What made the film an Indigenous medium for the Karrabing. On the one hand, the answer lies in how characters work in the films. Rather than one or two characters, everyone has their turn as a central character. This way of performing reflects a local performance aesthetics, wangga, in which performers both dance as a synchronized group and emerge from the group to show off their individual style. On the other hand, the answer probes the relationship between performance and knowledge. The more a person listens, participates, and embodies performance practices the more she discovers its truth. Not because they learn what the performance refers to, but because the truth is in the coming to embody the performance of it.

MA: How did you plan to use the money you won?

EP: We’re going to have a meeting and discuss that. Everyone wants the money to create the material infrastructures that will help maintain the Karrabing’s vision. Proposals include building an outstation in their remote lands, fixing the group’s boat, and passports and travel to international film screenings.