Margarida Mendes: Inhabitants, an online channel for exploratory video and documentary reporting, was launched in 2015 during a heated moment when activist struggles intensified in face of increased pressure by democratic and non-democratic regimes. Within this context, online platforms have become contested spaces of debate. Inhabitants works with short-form videos, published regularly as episodes on your website and on social media, which combine insightful reporting, verging on journalism, with a punchy aesthetics coming out of your background in visual arts and experimental film. What lead you to create this online channel?

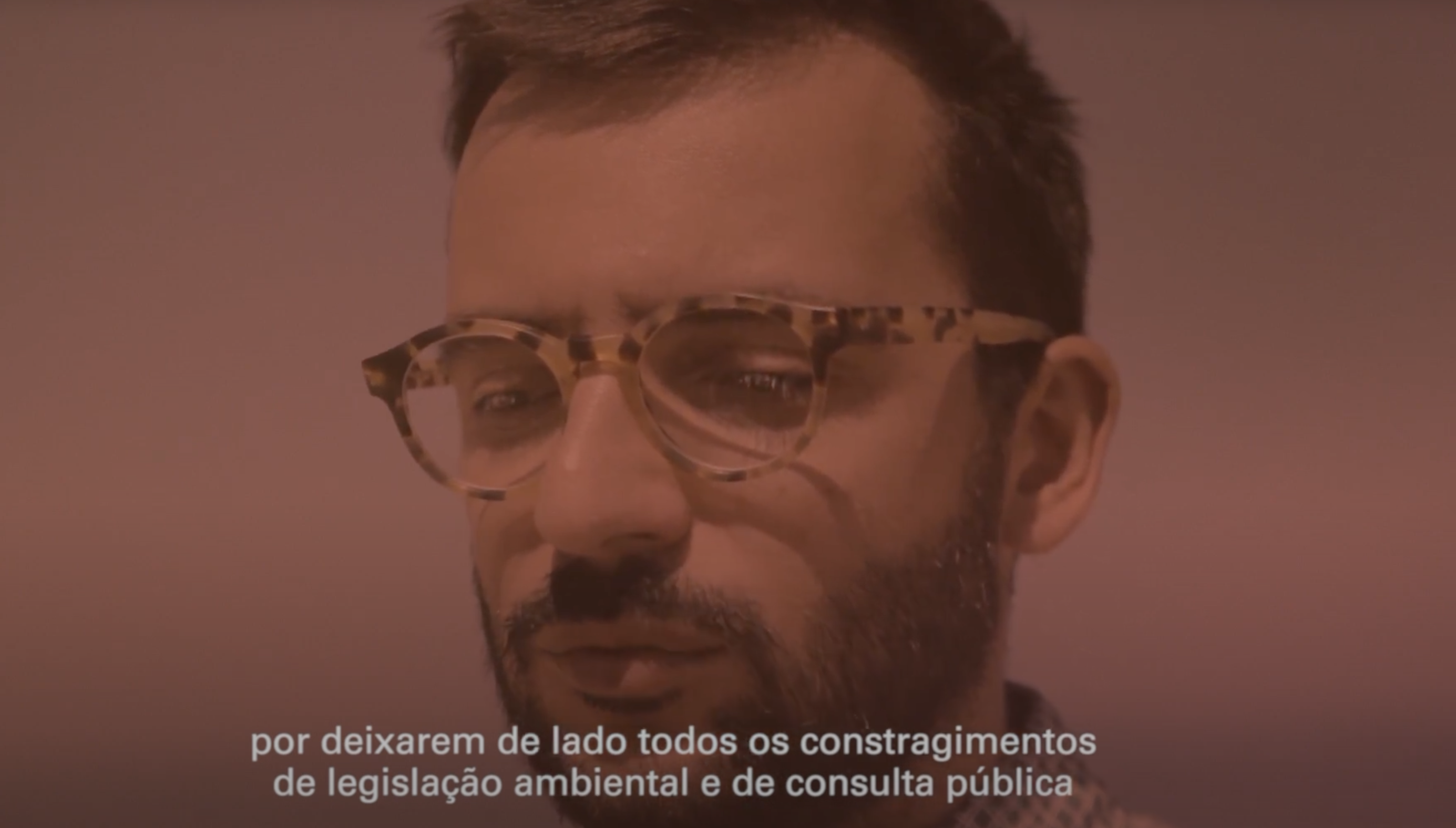

Inhabitants: Inhabitants asks broadly what media literacy means in the age of social media. In 2013 we shot a video, now listed on the website as a prologue, that ultimately became the origins of Inhabitants. The video was simultaneously a reaction to the closing of Greece’s public television channel ERT amidst the austerity crisis, before Syriza was elected, and a reflection about the generalized failure of television as a political medium. The video was very different from what both of us were doing individually as artists working in the contemporary art context, but being from Portugal and having just recently left the country because of the EU imposed austerity measures, we felt solidarity with the Greek resistance to the closing of its public services. We saw that in Greece the most interesting sources of information were coming from independent media, while ERT itself survived the stint by continuing to broadcast online, due to the stubbornness of its workers. This redirected our attention to online media in ways we hadn’t done before. It pushed us to begin a channel anchored on investigation, information, and distribution, akin to journalism in some ways, which offered us freedom from the arts context while still rescuing certain traditions of experimental cinema and the visual arts.

Inhabitants emerged out of this experience as an analysis of online video and the specific grammar, editing, and pace of its video formats intended for viewing and sharing on social media. In terms of methodology this implies, for every episode we produce, looking at online videos regardless if by major news outlets, activist groups, or amateur production, asking what they are introducing to our collective agency both at the level of video and film genres and in terms of distribution.

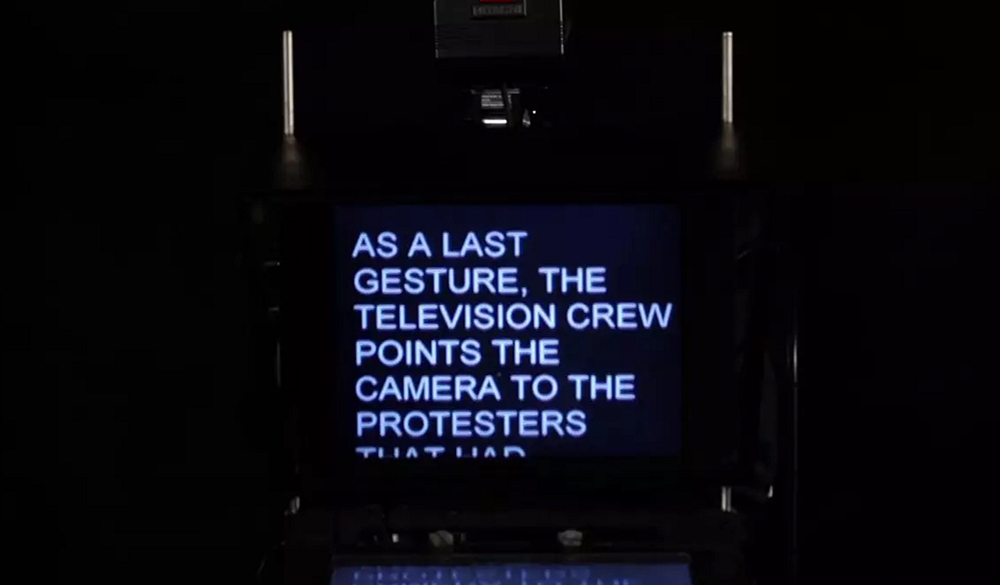

MM: There is an agential quality to the informational style of your videos. Particularly in some of them, such as How Does Video Become Evidence? you provide a toolkit for activists and protesters who use moving image as a form of contestation, or call for action, and in this particular case images can generate legal evidence.

I: Editorially, we have focused on different geographies, but we are based in the US and, especially after the Trump election, we wanted to contribute to the public discussion about transparency, police violence, body cams, and citizen watch. In the aftermath of several 2016 elections, the partiality of social media as a news source has finally been questioned, but also the efficacy of online activism. At the same time, one can see media being weaponized both by the police (and the state at large) and by civic movements. So on the one hand, you have media as self-defense; on the other, an increased questioning of the transparency and truth of media.

In terms of our working process, while most of our episodes deal with information and journalistic investigation done by us, when it comes to activism we prefer to follow the steps of people already acting on the ground in order to contribute to what they already set in motion. Similarly, while some episodes are more exploratory, fictional, and speculative in tone, for episodes such as How Does Video Become Evidence? our aim is to make content that may be practical and useful for people as well.

We have to acknowledge that since Rodney King and throughout Black Lives Matter it has been the violent and unjust death of black lives in the US that has brought this issue of video as evidence to the fore. So, in this case, we interviewed an NGO, a journalist, and an activist member of Copwatch (citizen-organized camera brigades that try to reduce police violence by recording interactions with the police), all of which are involved in the legal accountability of video evidence. With this material, we listed what makes a video legal in court, as well as how to film violence safely, and then redirected our viewers to the proper agents and activist groups.

MM: Much of your focus is dedicated to issues related with social justice, but also the defense of anti-extraction politics proposing a turn towards the green revolution. Can you elaborate on your thematic outreach and lines of programming over the past seasons?

I: In two years we have produced up to twenty-five videos, some of which on very different subjects and with very different aesthetics. And yet we feel we are still learning how to work with complex issues in a short-form video while keeping things formally interesting. That is, how to combine investigative reporting on given political issues while rupturing with expectations about how the form of such informative videos should look like. Unlike other platforms, we are not so much interested in a coherent theme, but in maintaining rigor and formal experimentation in our approach.

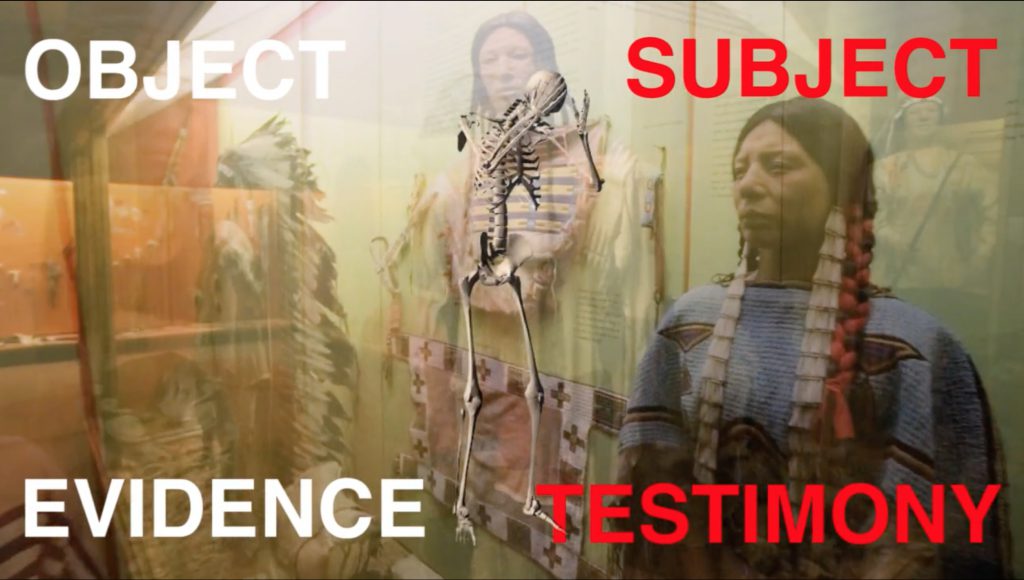

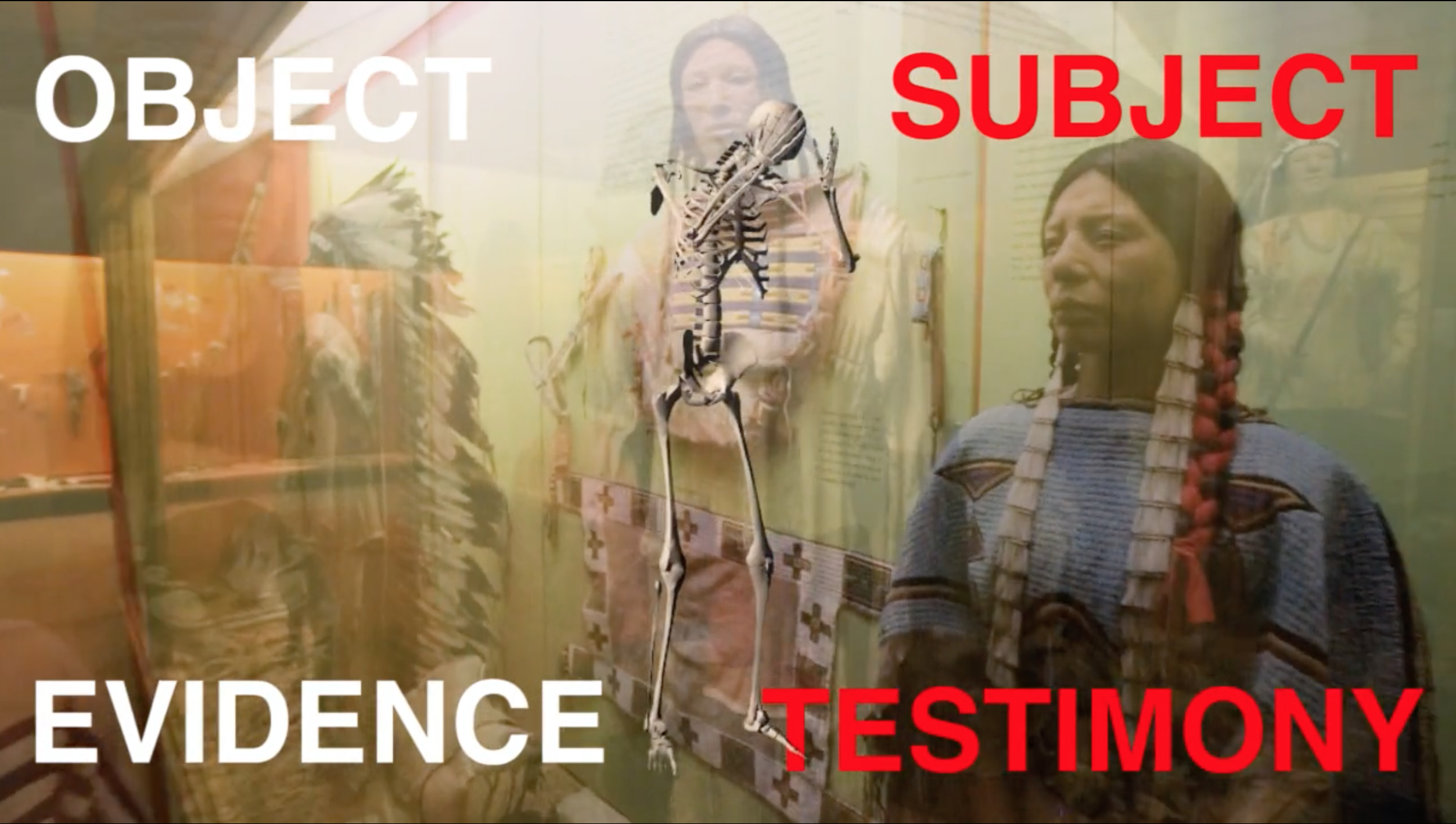

Starting with our episode A Brief History of Geoengineering, which looks at the economic interests behind technologies that aim at engineering the climate (carbon capture and so on), we have focused on environmental issues. This has translated into episodes on anti-resource extraction movements, for which we began to collaborate with activists for a better video distribution. However, we don’t make much of a distinction between environmental and social justice, as often these are connected. As such, recently we have focused on identity, gender, and indigenous rights.

MM: Inhabitants is also an open platform where other filmmakers and researchers contribute with films and share their research through moving image. The cautious selection of its contributors and development of its distribution strategies which aim beyond viral statistics is also an important matter. Can you tell us what is your circulation strategy?

I: Inhabitants is more of an editorial platform than an authorial project. Although we produce most of our videos, the aim has always been to open Inhabitants up to other filmmakers. This is something we are focusing on this coming third year of operation: not only funding and showcasing politically-focused filmmakers but also hopefully connecting their work with activist groups and movements. For the moment, Inhabitants isn’t really a self-sustainable model, yet we hope to work further in this regard.

In terms of distribution we’ve also realized that instead of aiming for a video to go “viral” it is rather more interesting to be in touch with activist groups and make sure they get access to the content, that they find it useful, and that we time each episode launch according to their calendar of events. This implies questioning the techno-utopianism underlying the social media hype, the market and algorithmic logic of virality, and the recent economic investment by news outlets in video content. We will continue to research meaningful ways to sidestep this type of distribution, the middlemen it creates, and the further concentration of power it can contribute to.

MM: Several of your episodes address resource management and follow recent struggles, such as the fight against oil and gas extraction in Portugal or the emerging Deep Sea Mining plans that are projected for the Pacific and Atlantic ridges projected to be a series of episodes in 2017/2018. These particular episodes are built as a series, tackling the complexity such themes from multiple angles and deploying diverse formal strategies, documental but also humorous. Can you talk a bit about this?

I: The video series is a way of approaching complex topics that demand of us a more narrative, chapter-like format, with each episode in the series focusing on a single aspect. We began the video series format with our Anthropocene Issue, continued with the anti-oil extraction series For an Oil Free Future, which reacts to attempts at oil drilling and fracking in Portugal, and are at the moment producing a five-part series on Deep Sea Mining. For the latter, we are mixing data-visualization episodes on the mining economy or deep sea biodiversity with more interview-based episodes in the Azores, where we will meet with local groups. Doing so also allows us to test diverse techniques, breaking with preconceived ideas about what a journalistic or activist video should look like. We have had some great surprises regarding how people are using the episodes!