Nat Muller: Together with architect Sahar Qawasmi you’ve been working on Sakiya for a number of years. Can you contextualise the importance of simultaneously reviving architectural practices, traditions and local knowledge in a place like Palestine in which land takes on such symbolic proportions? What are the consequences of the Israeli Occupation and the subsequent dispossession of (agricultural) land, as well as the increased urbanisation and growth of Palestinian cities, on the short and on the long term for the fabric of Palestinian society?

Nida Sinnokrot: The loss of land associated with the Israeli occupation is not only measured in the lost area but also in lost tradition, lost knowledge and the loss of cooperation. In the last 50 years building has replaced agriculture as the main source of employment with many young people seeking work in construction on Israeli and, more recently, Palestinian projects. As a result, there is a brain drain of sorts, a loss of knowledge as it relates to the land. In parallel, many of our historic architectural sites have agrarian roots, meaning the buildings themselves have a direct role in the production and preparation of crops. With the loss of land due to annexation and occupation and laborers seeking employment in the building trades, the original role of these buildings is lost, feeding into their disrepair. What if we could rehabilitate the land, would the historic building then come back to life?

In the past decade, we have been increasingly occupied and preoccupied with seeking security as measured by neo-liberal definitions of success. Consequently, competition is highly regarded whereas cooperation is nothing more than a catchphrase. Neoliberalism, NGO-ization, brain drain… all of this is cultivating a culture of dependency. Farming teaches us how to cooperate. In short, this is how we approach sustainability. And in our contemporary culture, we believe it’s the role of artists and cultural institutions to cultivate these benefits of sharing.

NM: Sakiya is conceived as a residency project. Why is the format of an interdisciplinary residency particularly suited for your objectives?

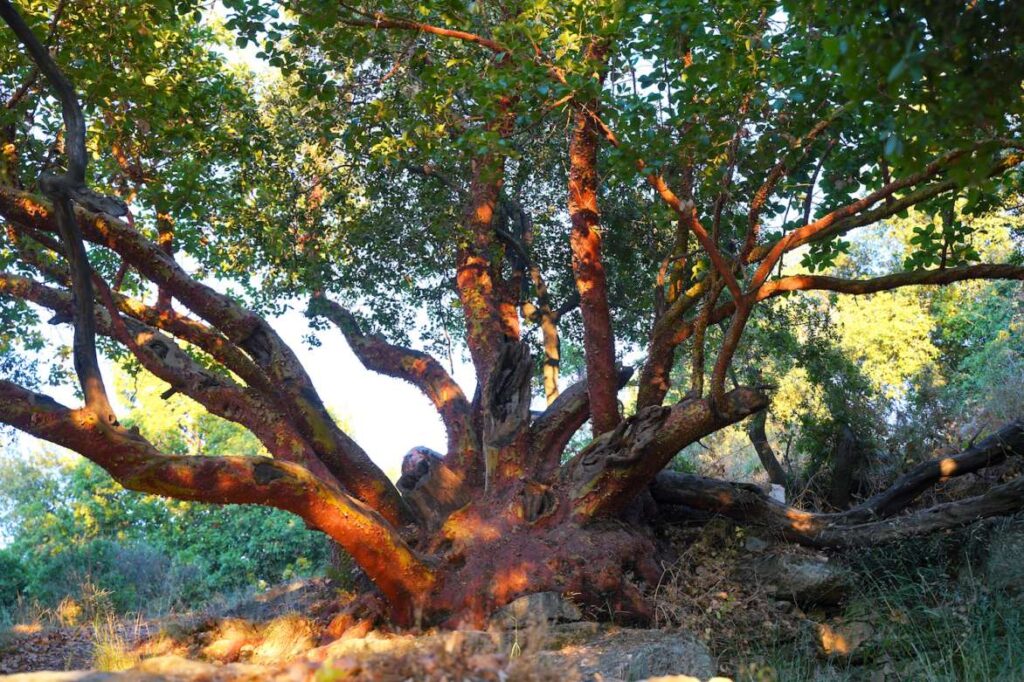

NS: That goes back to sharing. In permaculture there is the term ‘guild’ that refers to how different plants, when brought together, take care of one another, repelling bad insects or attracting beneficial ones. Similarly, bringing together fellows from different disciplines leads to cross-pollination and a sense of how individual practices relate to one another and share common objectives. Having someone well versed in contemporary Green Technologies working closely with someone who specializes in traditional dry stone wall building, here in Palestine could very well shed light on how these historic structures function as heat sinks, regulating temperature, increasing harvest output, creating microcosms for reptiles and insects, etc. There is another dynamic at play here and that is people sometimes need the interest of an outsider to recognise the value in what might otherwise have a stigma as being out-dated or old fashioned.

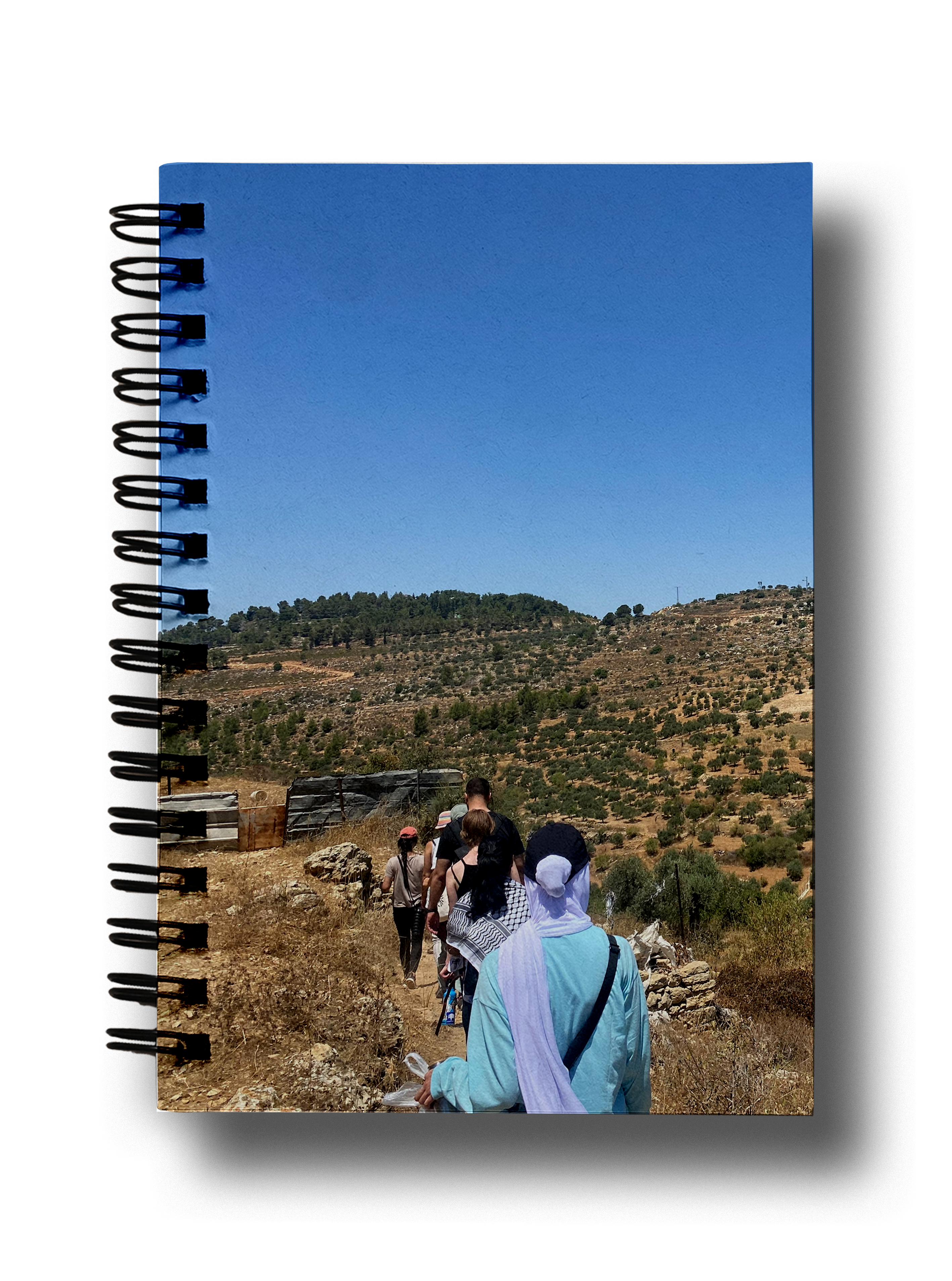

NM: In 2017 you were entrusted with the Zalatimo Estate, a 28-acre nature reserve in the village of Ein Kinya. How do the particularities of the site feed into the project and how are the local communities involved?

NS: Ein Kinya is a fertile agricultural village with springs, Roman archaeological sites and a rich mix of wildlife. Many inhabitants settled here from villages depopulated by the Israeli occupation so it is a wide representation of Palestinian culture as well. The older generation is well versed in traditional farming practices. We are very excited to tap into this wealth of knowledge. Sakiya will have residency spaces in Ein Kinya, as well as a restaurant run in cooperation with a local family where we will host visiting resident chefs and serve cross-over, experimental cuisine made from everything we grow on our farm. In keeping with our approach to renovation, we believe that rehabilitating the land through permaculture should happen in tandem to the physical stone and mortar restoration.

NM: Sakiya promotes merging the contemporary know-how of green technologies with traditional farming practices, however in the volatile political landscape of Palestine ‘sustainability’ is not a given. What safety mechanisms can you script into the project, if any?

NS: We are taking a long-term, systematic approach to cultivate sustainability through education. Once you have excited children coming home and telling their parents about what they learned from our resident fellows, you’ve set the wheel in motion. Our Summer Program will invite one student from each of the school districts across Palestine to live on our site, learn about permaculture, learn from the research and art projects that our resident fellows worked on, experience life without waste, eat what we grow and feel secure with what the land and their own ingenuity can provide. I have no doubt that this will reactivate a sense of pride in our youth and make a lasting impression.

NM: Can you talk a little about how this project expands on your own artistic practice and concerns? As well as how you specifically see the role of art at large in the project.

NS: My work tends to be concerned with systems – those that give rise to structures of control, for example, and how we can expose them to better understand our points of view. I’ve been increasingly interested in those systems at play in Palestine that foster individualism and competition as measures of success and as such, security. Art, in whatever form that takes, is the way I seek to balance this equation and shed some light on the forces at play here. I believe that artists, through their individual work as well as their collaborative discourse, production, and creative teaching, can directly address such complex cultural problems and provide critical frameworks that we need, in order to solve them. I see the work of Sakiya as an extension of my practice as an artist/educator. It has already become a dynamic classroom for the community in which it moves, where marginalized cultural actors, such as local farmers and craftsmen, are able to assume a prominent role in the creation of culture alongside visiting scholars and students.

NM: And finally, what are the first concrete steps and initial plans to rehabilitate and re-activate the Zalatimo Estate?

NS: The first step is to develop our Master Plan. Made in collaboration with our resident fellows, friends, and representatives from Ein Kinya this plan will represent our collective imagination and give everyone involved a sense of ownership in the project. Old and young, artists and scientists together will workshop how this hillside could evolve in symbiosis with Ein Kinya; how its crops could benefit the village, how the resident’s kitchen could generate income as a restaurant, how we can compost waste to make fertilizer… a complete ecosystem. This ‘imaginary period’ will be represented in sketches, models, artworks, research, and folklore… all of which will be presented as a public exhibition in our historic houses (before renovation) and published as a manual for sustainable rehabilitation and restoration. After this plan is ready and our collective imagination primed, we will get our hands dirty!