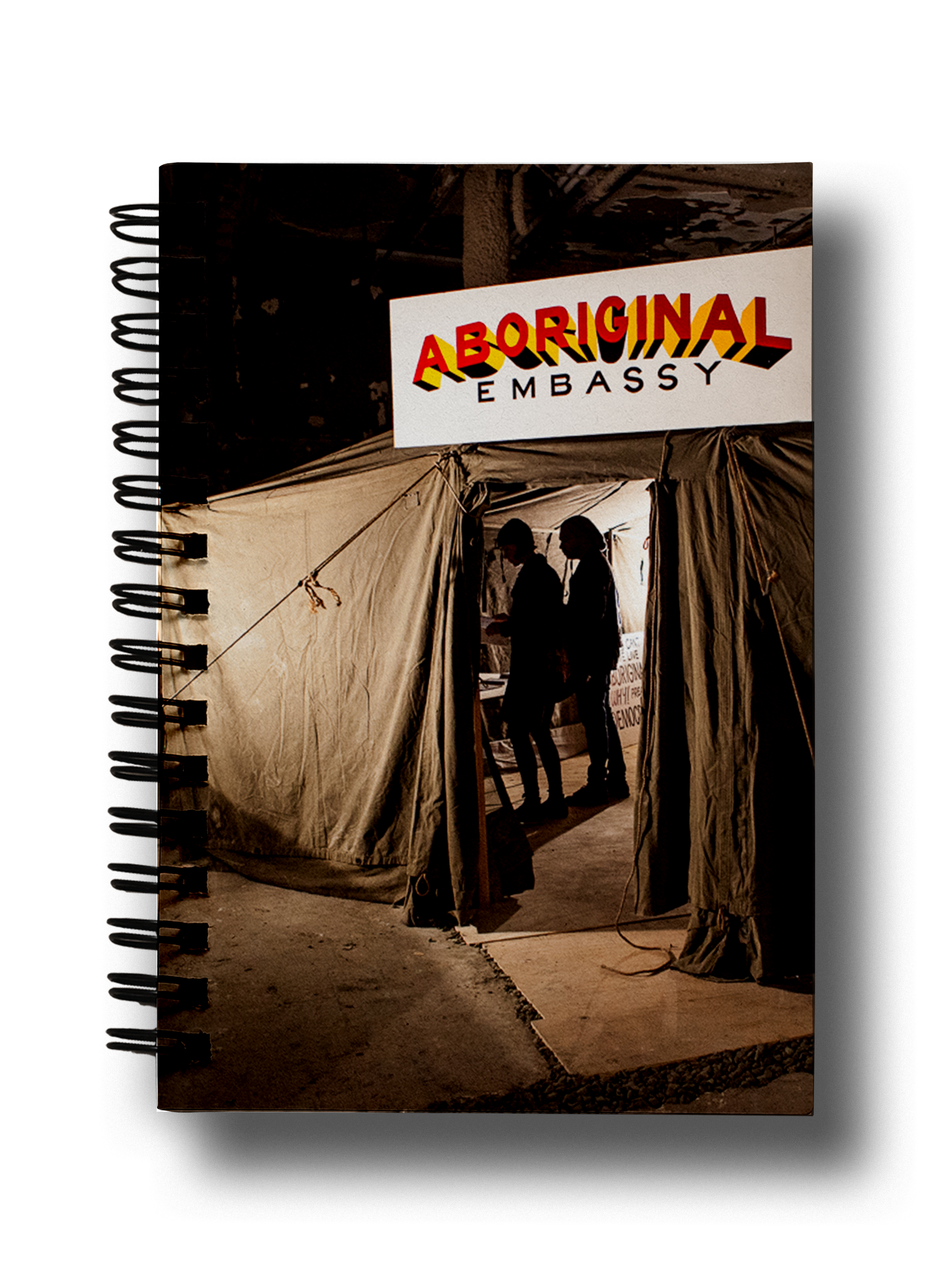

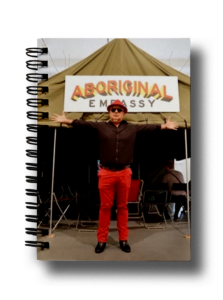

Richard Bell describes the first Aboriginal Tent Embassy on the parliament lawns of Canberra, Australia, on 27 January 1972 as ‘Australia’s greatest work of performance art’. Bell was born in Charleville in Queensland in 1953 and raised on apartheid-style reserves before seeing the historic event of the Aboriginal Embassy’s emergence on national television as a seventeen-year-old high school student. He was an activist and community worker before becoming a full-time artist and co-founding the Aboriginal art collectives Campfire Group in 1990 and proppaNow in 2004. He won the National Aboriginal Art Award for Scientia E Metaphysica (Bell’s Theorem) (2003). The piece was in response to the polemical essay he wrote the preceding year, ‘Bell’s Theorem: Aboriginal Art, it’s a White Thing’.1

An ‘imagined room’ of an Aboriginal Embassy already appeared in the artist’s very first institutional exhibition at the Institute of Modern Art, Brisbane in 1992. Since 2012, inspired by the next wave of radical Indigenous young people who are raising sovereignty issues directly, he has produced Embassy, a semi-curatorial initiative bringing the unique forty-plus year legacy of the Aboriginal Tent Embassy—the longest running pan-Indigenous protest camp in history—into dialogue with global archives of protest and performance through contemporary international art spaces.

The creation of the original Embassy was a reactive confluence of activism, protest and theatre. At an emergency meeting of concerned Aboriginal people in the Sydney suburb of Redfern in January 1972, it was deemed urgent and necessary to send four young men to Canberra to establish an Aboriginal Embassy. It was to be established on the lawns of Parliament House as a direct and immediate response to the then Prime Minister’s statement that his government would never give Aboriginal people land rights.

In his speech, McMahon acknowledged ‘the desire of Aboriginal people to have their affinity with the land recognized by law’, before insisting on barriers to their implementation2. Fifty-year ‘general purpose leases’ were proposed for the remote Northern Territory, while the Nabalco mine would go ahead. Elsewhere, Crown land, Aboriginal missions and reserve lands—to which Aboriginal people had been forcefully sequestered during frontier expansion and through the assimilation era—would not be made available to doubly dispossessed peoples. The statement was more assimilationism, eliding the difference of Indigenous landed economies and the moral-historic matter of land theft.

The ingenious idea of a flimsy, replaceable beach umbrella as a mimetic provocation to Australian sovereignty, representative of the actual conditions of Aboriginal life, is inseparable from the culture of 1960s Redfern. The Aboriginal population had surged there to tens of thousands from 1966–69, following the closure of reserves. Billie Craigie, Tony Coorey, Michael Anderson and Bertie Williams all had links with voluntary Black Power-influenced organisations— and their grassroots intelligentsia—running legal, health, housing and radical street theatre initiatives. Their first statement to media noted the government had rendered them refugees in their country, that this necessitated political representation, and that they would not move until national land rights were achieved. Discovering a legal loophole, their presence turned out to be entirely legal for as long as the number of their tents did not exceed eleven. A six-month-long battle played out with the government and police on national television, delivering the direct demands and aesthetics of the Australian Black Power movement as a land and cultural rights project to the TV and radio of eighty-two countries.

Besides labour unions, the most significant support came from Australian National University students in a manner that recognized the self-determined movement would no longer be benevolently white-advised or infiltrated. It was the first time the state’s monopoly of violence over the lives of Aboriginal people since invasion had been so publicly screened and deconstructed for national audiences, through a very fine balance of returns of threat, uncompromising leadership, theatre and non-violence. Land justice was finally rendered a competitive party political issue concerning the nation. The matter of their non-delivery, beyond the 1975 coup against Gough Whitlam and later betrayals by the Labour party, is extensively documented by one of Bell’s key collaborators, the Aboriginal historian, actor and Black Power activist Gary Foley.3

It is difficult to summarise the impact of Embassy as a roving oral archive, open mic infrastructure and iconic unrealized justice claim connecting shared histories of struggle—also against forces of recuperative governments and revisionist academicization4. At the 2013 Moscow Biennale, Embassy posed questions of art and revolution beyond East–West rubrics, connecting critical conceptualism to the matter of Empire. At the Jakarta Biennale in 2015, Indonesian and Indigenous artists discussed their shared experiences of Dutch and Australian imperialism impacting the regional geopolitics of contemporary art. At the Twentieth Sydney Biennale, the program foregrounded past and present contributions of Tent Embassy women activists and artists with Lorna Munro, Angeline Penrith, Bronwyn Penrith and Jenny Munro among others. In Jerusalem, the Tent sub-hosted translational space including for the practice of the Karrabing Film Collective, speaking in their third and fourth languages to their Palestinian hosts’ frontier context. New York’s Performa 15 provided an important occasion to unpack for a US audience, and vice versa, the non-identical claims of US Black Power, Garveyism and Indigenous rights, which uniquely threaded pan-Aboriginal internationalism in Australia. Bell’s collaboration with Emory Douglas, Minister of Culture for the Black Panther Party—repeated in Amsterdam for a mass audience of inspired young people—asserted the role of long-running protests as shareable heritage for new practices. The conditions of racialised life in settler colonial Australia were discussed with #BlackLivesMatter and Idle No More, while Mohawk artist-curator Alan Michelson, co-founder of the Indigenous New York initiative, drew out the common struggle of visibility for urban Indigenous artists.

In 2019, Bell has fundraised to bring leading Aboriginal historians, cultural theorists and artists into dialogue with friends gathered from Embassy’s previous stagings at the art world’s ground zero: Venice. This, following his rejection by the official Australia Pavilion selection process, evidences his tireless collaborative energies. So too does a replica he has made of the Australian Pavilion wrapped in chains, floating past the canals for the purposes of propagandistic media exposure of the shameful ongoing treatment of Indigenous peoples in the rich nation. Many of these interlocutors have seen the previous decades’ rise—and debilitating fall—across every policy portfolio, including art, of the ‘Aboriginal control of Aboriginal affairs’, made possible by the land rights era of activism. Bell as casual ringleader and disarming provocateur of what is and has been possible, shines to his own peers as someone protecting space for culture and candour against extinction-oriented norms of production.

1 Richard Bell, ‘Bell’s Theorem: Aboriginal Art, it’s a White Thing’ (November 2002), http://www.kooriweb.org/foley/great/art/bell.html.

2 Scott Robinson, ‘The Aboriginal Embassy, An Account of the Protests of 1972’ in Gary Foley, Andrew Schaap and Edwina Hall (eds.), The Aboriginal Tent Embassy: Sovereignty, Black Power, Land Rights and the State (Abingdon: Routledge, 2013), 3.

3 Gary Foley, ‘Native Title is Not Land Rights’ (1997), The Koori History Website Project, http://www.kooriweb.org/foley/essays/pdf_essays/native%20title%20is%20not%20land%20rights.pdf.

4 Gary Foley, ‘Black Power, Land Rights and Academic History’, Griffith Law Review, 3 (2011).