The bill arrives, crisply folded in half to avoid immediate scrutiny. After an exchange of niceties, you pick it up, flitting through the neat list of printed numbers. In this moment a chain of events draws to a close; a meal extracted, delivered, cooked, served, eaten, and now, counted. And yet, what costs play out across time and space in ways that remain hidden, expunged from the receipt in front of you?

Salmon evolved long before homo sapiens. From their position below the water they have observed the full timeline of human history. Across plural, distinct worlds; from Indigenous Peoples in places known as Canada and Alaska, to rural communities formed around rivers in Northern Europe; Salmon hold cultural significance, shaping the lives and communities that have been built. Since the 1970’s however, in many places the relationship between salmon and humans has been changing rapidly. Heralded as a healthy and affordable form of protein, one might now encounter salmon in train station sandwiches, or airline meals, more often than in rivers or streams.

arrow_upward

arrow_upward

Along the west coast of Scotland lies the Isle of Skye. Arriving at the island by ferry, dark circles can be seen in the water forming punctuation marks against the shoreline. Above the surface one encounters a pristine landscape, yet below the water a reduction of worlds is taking place. Nets hold congregations of salmon, grown in captivity to meet the appetite of the global market. Intensive farming creates a series of excesses that build up and cause breakdowns. Waste falls through the nets onto the seabed, depleting oxygen levels and creating dead zones where biodiversity is lost.

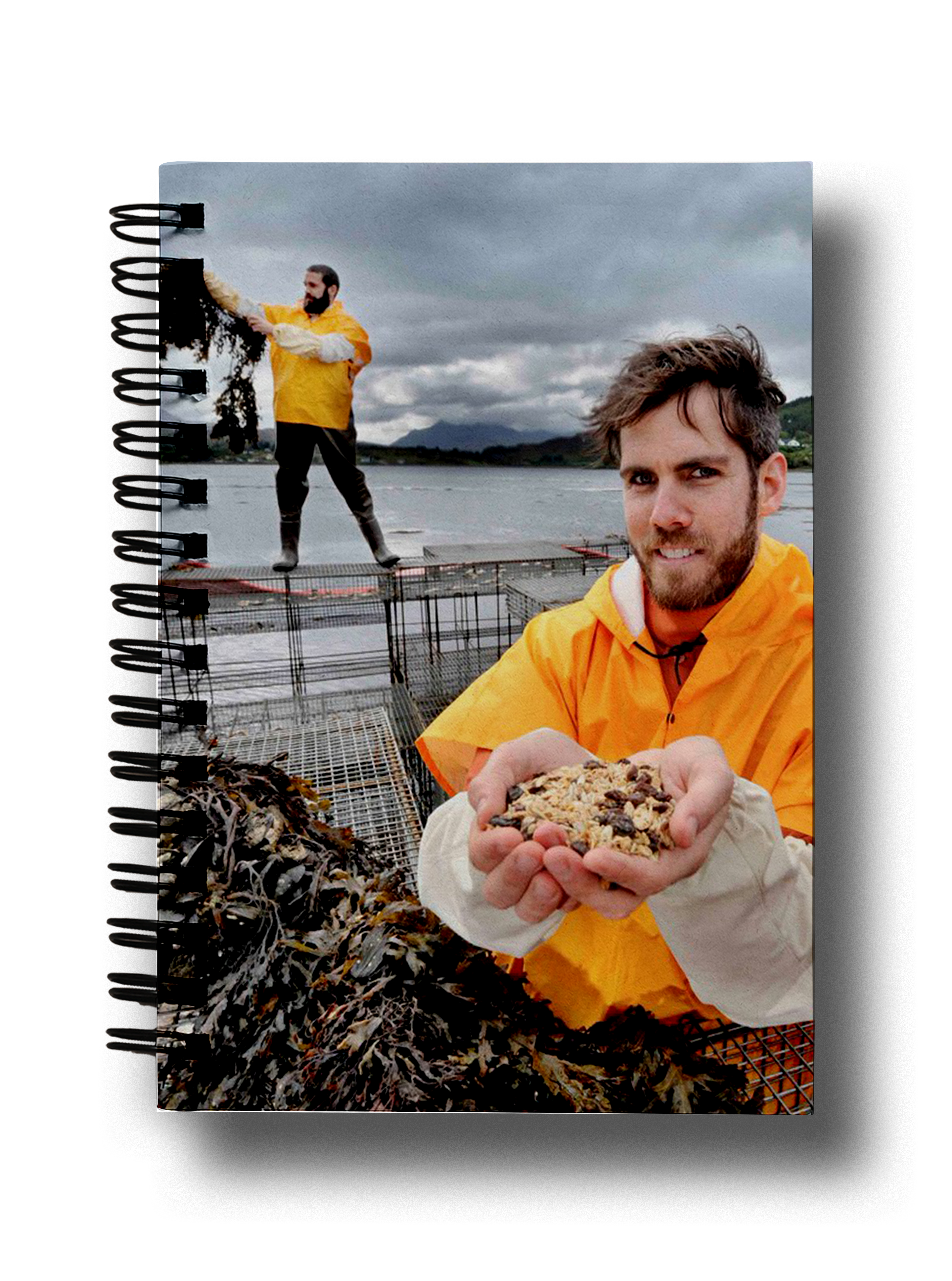

A wide chain of environmental consequences can be traced from this location. Salmon are fed on a diet comprised of ingredients including small, wild-caught, oceanic fish; anchovies from Peru, sardines from west Africa. Hungry appetites demand quantities that deplete the waters from which they are drawn. Communities held apart by geography are brought together through webs of consequence.

Returning to Skye, on a small island, every job counts. However, the salmon farming industry, dominated by multinational companies, does not have a long-term responsibility for this place. I spoke to a local fisherman, who noted: “It’s not a sustainable future for anyone here. It you look at the mining industry, as soon as they find a cheaper and better alternative they just pull out and they leave you. This situation is similar, we should not be leaning on these industries to support our communities. We should be trying to find more sustainable ways of doing things.”

Skye has long been shaped by the relationship between land, agriculture and labour. Over 200 years ago, inland communities across the highlands were uprooted and dispossessed to make way for the oncoming economy of sheep farming. During these clearances, many of the displaced found their way to the shoreline, building new ways of living; fishing through tidal traps, or farming kelp. It is here, returning to the shoreline, that the possibility of new models can be found.

Climavore, led by artist-duo Cooking Sections, asks how one might eat in a changing climate. No longer carnivore, omnivore, vegan or vegetarian; as seasons dissolve and unexpected climate catastrophes increase in frequency, Climavore considers modes of eating-with and alongside other species. A table built from oyster cages acts as a model for the project. When the water rises, the table is submerged, allowing its residents – oysters, mussels and seaweeds – to breathe, cleaning the surrounding waters; one mussel can sieve up to 25 litres of water a day, whilst a single oyster can sieve up to 120 litres. At low tide, the table emerges from the water to provide a space where humans can gather and organise. Taking a seat, to your left is a local councillor, to your right a fisherman. The conversation is hopeful, enlivened by the possibilities that emerge when multispecies communities work together.

The practical actions that have emerged from the table so far have included 11 local restaurants removing salmon from their menus, to be replaced with Climavore dishes. Salmon is lucrative; it possesses high profit margins, due to the efficient and destructive ways in which it is produced and the fact that people come to Scotland to consume the national symbol. To see restaurants remove it from their menus, demonstrates the strength of local support.

How might this vision be expanded? Next to the shoreline in the village of Portree sits an old ice house, a thick-walled 19th century structure that was built to store ice, cut locally in winter to be used throughout the year. This building, now in a state of disrepair, will be transformed into the Climavore station; a permanent cultural centre that exists to develop the vision of the project. Imagine walking through the door to find lawyers, scientists, artists & activists, working together. The station will hold a research studio, a think tank and a food lab; picture community meals, alongside evening classes on setting up your own Climavore business. The station will rebuild local systems from the ground up, placing the future in the hands of those most affected.

The creation of a Climavore station will see this project reach its full potential on Skye, whilst acting as a prototype for future international work. As Cooking Sections are currently developing Climavore projects in locations from Istanbul to Sicily, the model is one of long-term, international potential.