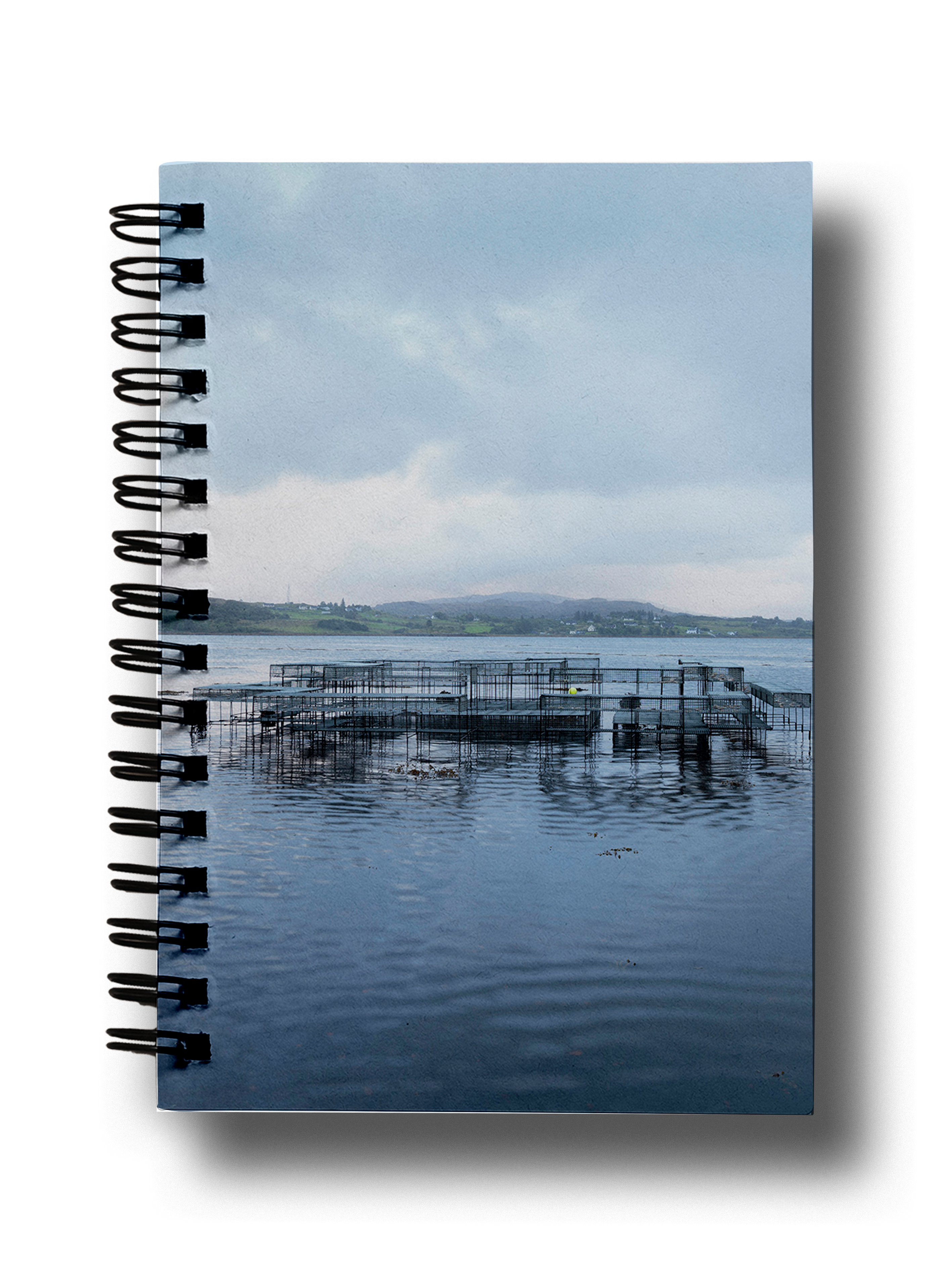

Small events sometimes make a big difference to life afterwards. It seems that Scandinavians imported a Japanese floating pocket net in the 1960s and that this import opened the large-scale farming of salmon, which in turn changed salmon from a luxury food for urban dwellers to an ordinary commercial product, available year-round, like factory chicken or rock-hard strawberries. In contrast to the smaller scale of freshwater aquaculture, salmon farming could tap the vastness of sea coasts, creating the first great feedlots of the ocean. Salmon farmers were able to ignore the waste their farming produced and to pretend that they were creating wealth out of nothing when they imported great quantities of Peruvian anchovies to feed their new commodities, thus depriving the southern oceans of fish. Salmon farming brought what Donna Haraway has called the Plantationocene into the ocean: the ecological simplification of life zones to the detriment of non-commercial organisms; the reduction of human work to mechanization and unfree labour; the mechanisms for proliferation of pests and parasites; and the conversion of space into respective zones of profit and sacrifice. While entrepreneurs hail the new domestication of the oceans, some conservationists and coastal residents, such as those North American indigenous people who watch the plight of endangered wild salmon, protest the outrage of using coastal waters as waste-producing and resource-hogging factories.

The art collaborative Cooking Sections went to the Isle of Skye to see the work of the fish farming factories there and, in reaction to the horrors they found, to imagine a different relation between people and food. Rather than merely offering something to look at, they began a practice combining observation and eating. Molluscs, they learned, clean up pollution when they filter water through their gills. Raising oysters and mussels, they suggest, is a better practice than growing salmon. Molluscs eat from the sea, rather than needing imported food; they leave the sea cleaner rather than excreting new wastes. So far, at least, their cultivation has not been associated with new pests and pathogens, which, in the case of salmon, plague all the surrounding fish.

Cooking Sections reimagined the spaces off the coast as the ‘tidal zone’ and asked participants in their project to imagine themselves living with the tides. The table they constructed to both grow and eat oysters drops into the water at high tide and rises again as the water recedes. This is a space to remember living within ecological systems rather than—like the salmon pens—shutting out local ecologies in the name of factory production. The diners join the oysters in immersing themselves in the tidal zone. They imagine breathing itself as a regeneration of the coastal waters; breathing is a practice shared by humans and oysters, and it brings us into joint company.

There are also plants here: seaweeds, such as dulce and kelp, which have learned to live with the tides. These seaweeds enter Cooking Sections menus along with local mussels and scallops. Eating each other does not destroy the tidal zone, in this conception; instead, it reaffirms the necessity of living together. Eating with becomes a practice to be contrasted to eating against. In the latter, the planetary environment suffers every time we take a bite. In the former, we reaffirm our residence in a common zone of more-than-human liveability. Eating oysters and seaweed immerses our senses in the tidal zone, reminding us where we are and what we have to lose.

In the twentieth century, most people, and especially ‘experts’, thought that all growth was good. In the twenty-first century, those dreams of growth as wellbeing have stopped making sense. The powerful agro-industrial system that rules our food production has created forms of ‘too-much-ness’: too much of the world’s animal biomass is livestock, which in turn produces too much chemically-led feed production, too much waste, and too much growth for virulent pathogens, which in turn creates too much of a rift between biosecurity, where delight in food is subordinated to chemical control, and sacrifice zones, where no one cares. Too-much-ness involves proliferation without attention to mutual liveability across species, ecologies and regions. Salmon farming on the Isle of Skye participates in this too-much-ness.

Cooking Sections has us imagine the dynamics of eating, from the smallest plankton to the mass production of flesh. As participants dine on molluscs and seaweeds, they might imagine the tiny floating beings that also sometimes participate in too-much-ness, as in harmful algal blooms, and yet, when considered within the ‘tidal zone’ of multispecies breathing, are known to be the base for most life. Tidal zones of multispecies liveability are also found in our intestines. Bacteria break down our foods so that we might benefit from their nutrients. Without such multispecies action, we would starve, even amidst plenty. The too-much-ness of factory farming, with its species segregations and rigid boundaries between production and waste, might be a version of such recipes for eventual starvation. In contrast, Cooking Sections meals place eaters in a zone of biological multiplicity, the better to appreciate the multispecies interactions necessary to eat well.

Small events sometimes make a big difference to life afterwards. Cooking Sections offers the promise of new relations between eaters and eaten, the better to hold on to earthly survival.

Anna Tsing