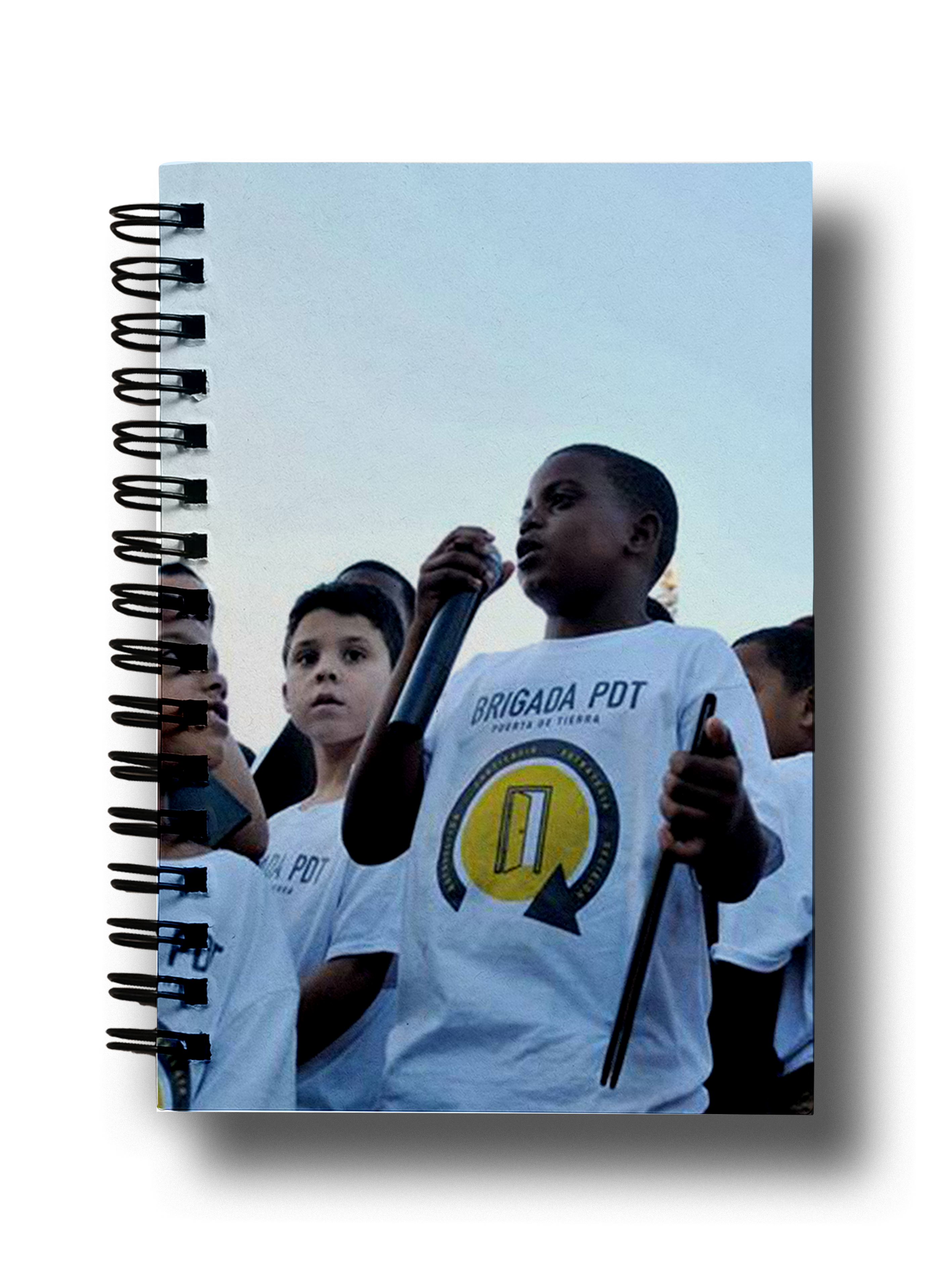

Jesús Bubu Negrón: La Brigada started as an immediate response to the systematic destruction, abandonment, and dispossession of the Puerta de Tierra (PDT) neighborhood. It developed quite organically, through observation and listening, and the shared recognition that we are all affected as neighbors by these processes. Our initial goals were to reactivate the communication and solidarity bonds in the community by organizing initiatives aimed at the rescue of the neighborhood, its history, and its people. Since 2014 we have recovered derelict spaces together with the neighbors and the drug users that inhabit them, to stop speculation and development, but also to prevent the spread of Zika and other diseases. This is also connected to the creation of common and neutral spaces in the neighborhood that enable a sense of belonging, which has been constantly undermined. These spaces are the Infanzón, which should become a community center; the bus stop under the Almond tree, in collaboration with the architects of Taller Creando Sin Encargos; or the Vivero square, with a community garden, an information station, and place of encounter, used by citizen lobby groups and hosting film screenings. Other aspects of our work deal with developing empowering tools for social leaders and the area, such as self-management, participation, and other creative strategies. Although we visualize our project as long term, the work is set in an atmosphere of proximity, focusing on small daily actions that work towards the bigger goals. There is a pedagogical and artistic vector that crosses everything we do, connected to taking charge of the reality of the neighborhood and understanding ourselves as active agents in its transformation and its future. This is especially important given that we mostly work with youngsters, which serve as a catalyst to the rest of the community.

Luis Agosto-Leduc: There has always been vision and strategy, but we have also allowed ourselves to be spontaneous, to get carried away by emotion and the moment. It has had its ups and downs, but we are always refining our ways of doing. We have been aware that we are not able to change things on our own, so the transfer and sharing of our abilities are vital. We are not referring to painting, but to developing a collaborative attitude of awareness, participation, and evaluation through a sustained exchange. And from there, to design tactics, direct actions and develop structures to maintain these processes in the long run that could be collectively implemented,

Julia Morandeira Arrizabalaga: What do you feel has been the most important change, and what are your biggest challenges now?

B: One of the most significant improvements is that today BPDT has become an official voice of the community, both internally and externally. It has a very active role in the media representing and denouncing our needs. Young people in the neighborhood are becoming conscious of the importance of community leadership, and the cultural arena that had been abandoned for decades has been reactivated. Also, we have managed to raise interest in other community groups and encourage collaboration with them. And we have raised attention both locally and internationally of what is going on in PDT.

L: With the Infanzón on our horizon, our main challenge now is to build a sustainable economy. We have been working on the basis of voluntary exchange of actions and services, but we need to be self-sustainable and autonomous. We are now researching different cooperative economic models that could suit us.

arrow_upward

arrow_upward

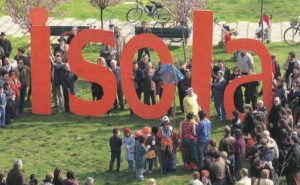

J: PDT lies in a territory with a long history of collective resistance movements and solidarity networks, the first one being its origin as a maroon community right after the Spanish colonial invasion, which I find pretty significant. A community built amongst runaway African and indigenous slaves from neighboring islands amidst and against the genocidal violence of the colonial rule; a transcultural territory experimenting with diverse forms of communalism such as the agricultural gardens that survived until the turn of the 19th century. These are resistance networks made up of alliances between people excluded from all forms of representation. I am not trying to romanticize it here, because violence remains violence under any form. But I think it is important to take this into account in order to imagine the genealogy of the place. In the 19th century with the hygienist project of mestizo elites and their European city ideal, city walls were demolished to avoid all types of plagues, human and bacterial, and the processes of exclusion and marginalization started in PDT. The area saw the articulation of the workers’ movement¹ and the circulation of all types of capital, goods, and people. From that time, PDT became a laboratory for population management, through public housing residential such as the Phalanstery where you live, named after the socialist utopian project of Charles Fourier. All of this was used to project an image of ungovernance upon PDT.

B: We are not doing anything new here: this is a fertile territory of protest and civic organizations² fighting urban planning and expropriation. It is more of a spark that has reignited something that remained dormant. PDT has been a thrilling and combative neighborhood, and that pride can still be traced from salsa songs to the lives of many people that came from here and excelled in all aspects of arts and politics. The Security Committee³ and the fishermen organization remain from that time. But then something neutralized that force, something that has extended to the rest of Puerto Rico.

With or without the crisis, PDT has always remained the black sheep, while Old San Juan is the nice face for the tourism industry, while history has many faces. In the 90s there was a huge housing project named Las Acacias, extremely violent and driven by the narco-trafficking. The only solution they found was to demolish it and from then on, the neighborhood gained a reputation of being a drug infested and unruly territory, which served to justify the processes of gentrification and generate social rejection – even I used to be afraid to walk down those streets.

People have been progressively deprived of their most basic rights here, and their political agency neutralized. All of my neighbors live in public housing, meaning that they are not owners and that they can be easily kicked out and relocated elsewhere. Property defines your citizenship spectrum here. Added to this we are very used to witnessing the state’s brutality, it is easy to understand why it’s hard for them to protest in conventional ways. Peaceful demonstrations here are equivalent to tying yourself to a tree, and the government knows how to respond too. So we added the recreative side to it, in order to attract people and make them feel at ease with protesting. An example of this are the murals, which indirectly, managed to signal the traffic issues we have to endure.

L: Our work stems from a political aesthetical position. We turned to artistic strategies because it is what we know best and because of the communication potential they hold. That is how we started producing memes and painting murals, which shifted from a confrontative language to the celebration of the neighborhood’s culture. “Aquí vive gente” was a direct response to the government plans that stated that the area was up for urban renewal because no one lived there; the message had a strong impact. With Raphy Leavitt’s and Sammy Marrero’s⁴ murals, it was different: the neighbors saw themselves represented, got involved and took it as theirs, planting flowers and organizing events under them. The murals are really an interface of many sorts of exchange. Every time we start painting, people will come out and give their opinion about it. We incorporate their views and change them. It is all a question of listening. Things change because people listen.

1 During the XXth century, PDT became an important economic harbor given the presence of the tobacco factories, TV stations and the harbor, which in turn developed other parallel economies: dog races, gambling, and betting, laundries, etc.

2 In 1879, a civic movement of PDT neighbors started at the time of the construction of the Ubarri tramway, connecting San Juan and Rio Piedras, which demanded the recognition and construction of several urban elements.

3 The Community Security Council Puerta de Tierra defines itself as a group of neighbors working towards the improvement of the security and life quality of its community. The Villa Pesquera La Coal association is the second oldest fishermen association in San Juan.

4 Raphy Leavitt (1948 – 2015) was a salsa musician and composer, founder of the orchestra La Selecta, and born in PDT. Sammy Marrero was the voice of La Selecta, and lived for years in PDT.