A widespread feature of the dominant Danish national identity is the idea of Danishness as equivalent to democracy, respect, tolerance and freedom. By this logic, it follows that racialized minorities in the country, including refugees and migrants, are often seen as undemocratic, disrespectful, intolerant and totalitarian. This sense of Danishness additionally supports the belief that racism does not exist in Denmark¹, and has been instrumental to the political parties’ increasing tendency to implement racism through the law², through the construction of refugees and migrants as a problem often connected to crime, to be handled through stricter laws, more control and more law and order³.

The criminalization of refugees and migrants started towards the end of the 1980s and then developed further towards the introduction of stricter immigration laws and restrictions to migrants’ rights in 1997. This development has continued until today, and the latest changes to Danish immigration law have moved towards an ever more selective control of foreigners based on general categories of persons.4 This categorization includes a legally well-defined group consisting of refugees and migrants arriving in Denmark until the late 1990s, their children (and grandchildren), as well as asylum seekers and rejected asylum seekers. This group of people faces severe restrictions to their rights, as well as stricter punishments for infringements to the law and harsh conditions in matters pertaining to family reunification, asylum, visas and deportation.5

Over the years, the criticism made by a number of international and European bodies of how the Danish state carries out or sanctions racism has either been directly rejected or ignored by ‘official’ Denmark: ‘In most cases neither the media nor politicians have considered it relevant to take the various points of criticism or the recommendations seriously.’6 The tendency to avoid taking seriously the problems of racism and racial categorization has also affected representation and framing in the media, where political spin has been an important element in legitimizing racism as the basis for political decisions.

As mentioned earlier, this framework also produces the idea of the criminal migrant, which allows for the highly problematic application of criminal law on refugees and immigrants. During the past two years, ‘state-imposed parallel legal and regulatory regimes for groups of people framed as culturally and religiously antithetical to Danish “democracy” and “tolerance”’ have emerged. Notable in this concern is the ‘asylum package’ from 2017 and the ‘ghetto package’ from 2018. While the former involves severe restrictions to the right to family reunification and citizenship laws, and reduces social benefits for refugees below poverty levels, the latter ‘includes differential laws and governance for residential areas populated by a majority of nonwhite residents’.

With this shift, the Danish authorities can now apply parallel legal and regulatory regimes in a differentiated manner to specific populations in Denmark. These populations, citizens and non-citizens alike, find themselves confined within legal and regulatory regimes that appear as a de facto regulation against their existence. Indeed, these regimes subject these groups to conditions that produce their political, social, cultural and real death by applying structural forms of violence spanning criminalization, deportations, detentions and differential access to healthcare, education, housing and social participation.

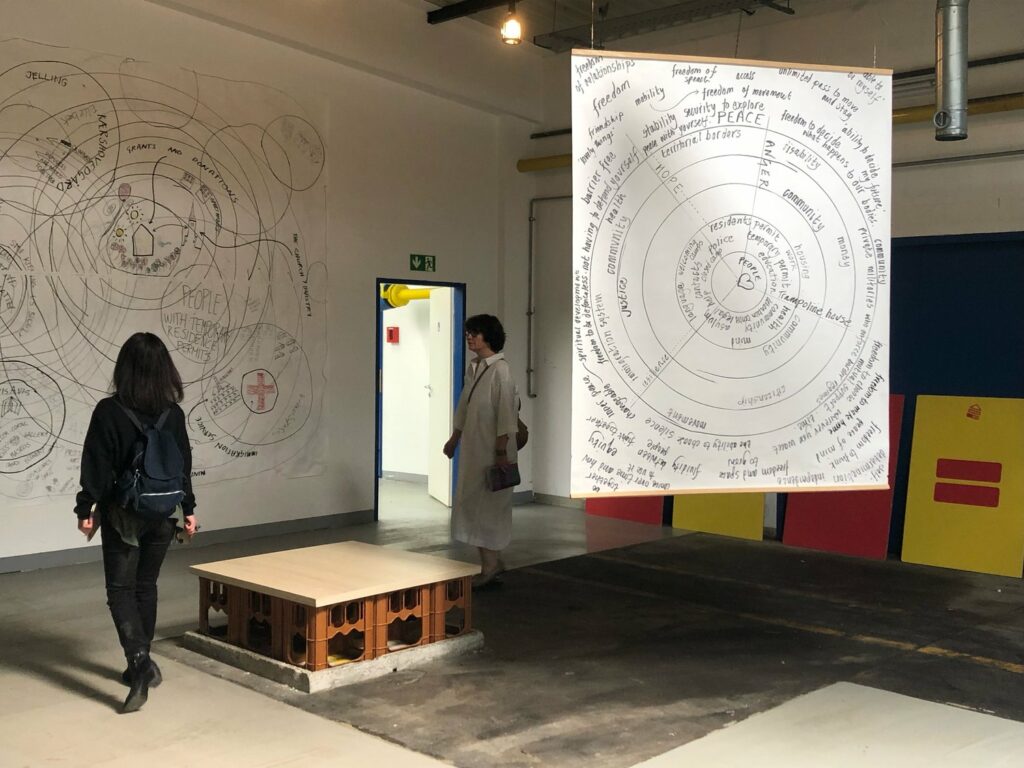

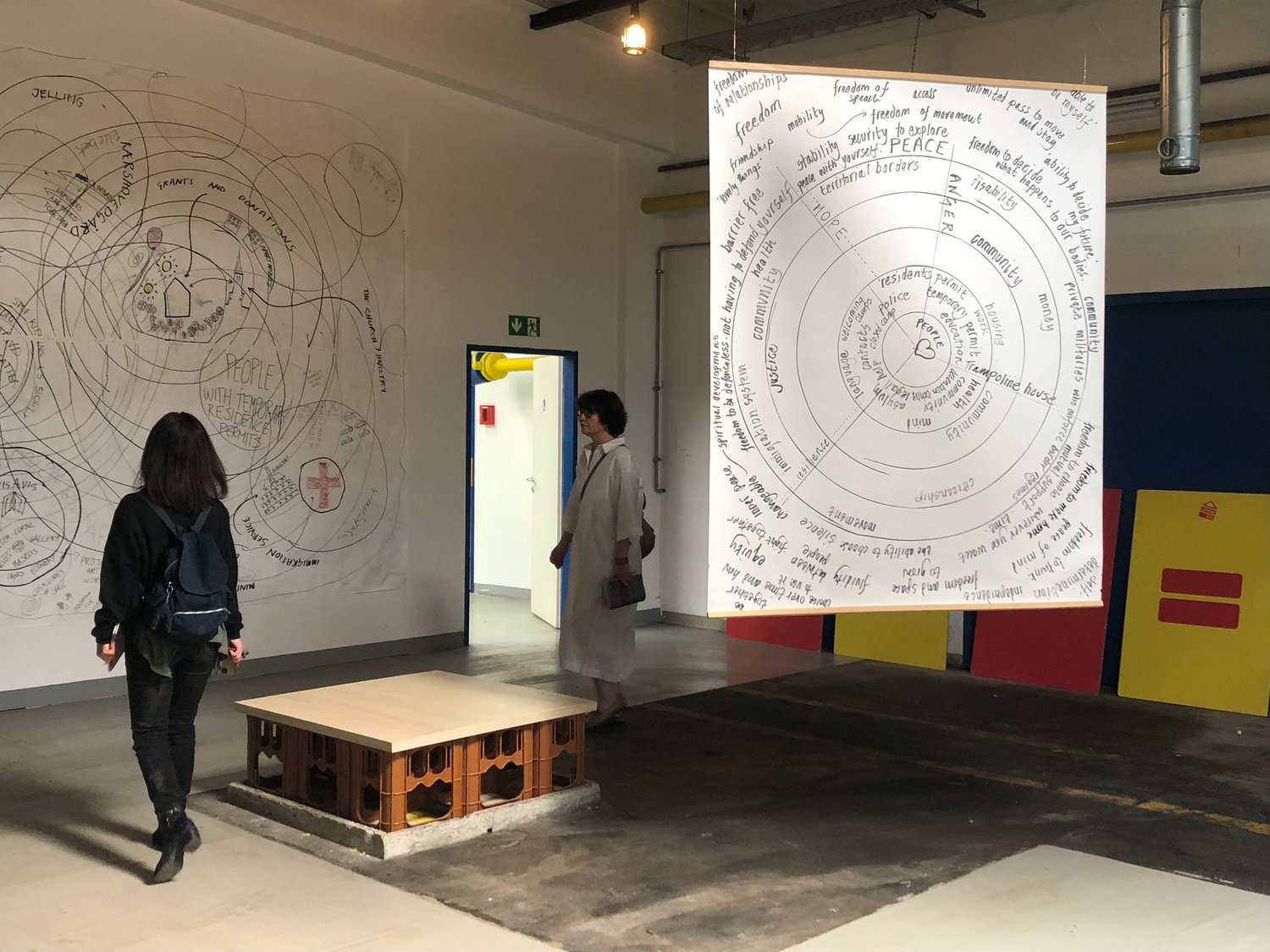

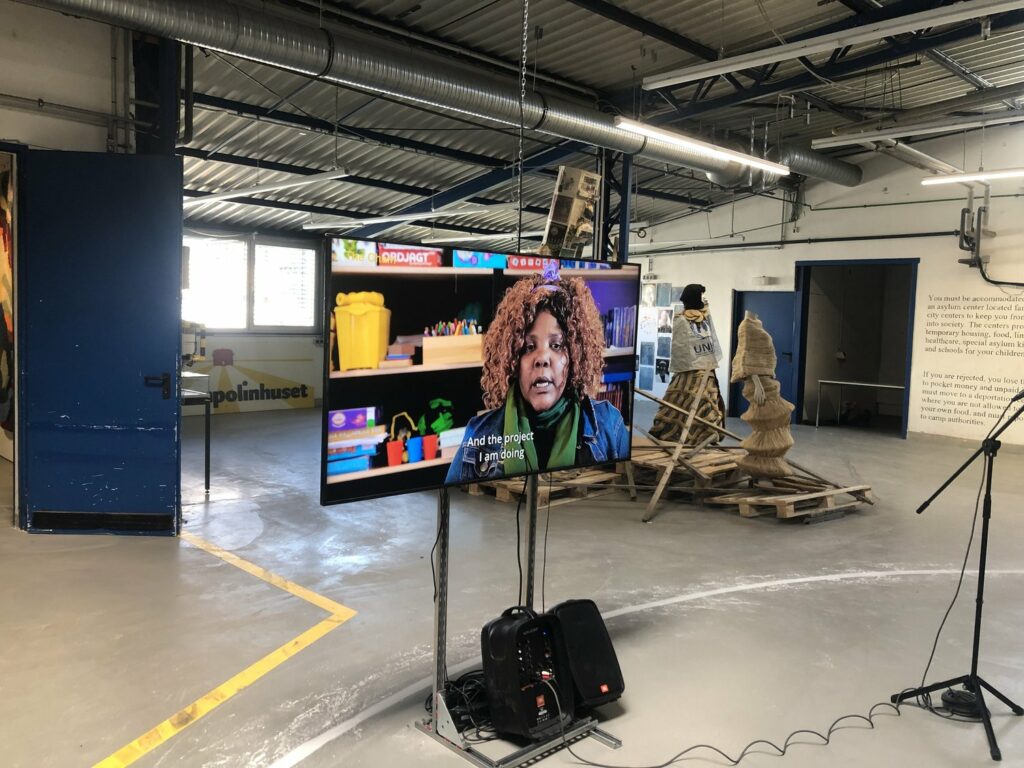

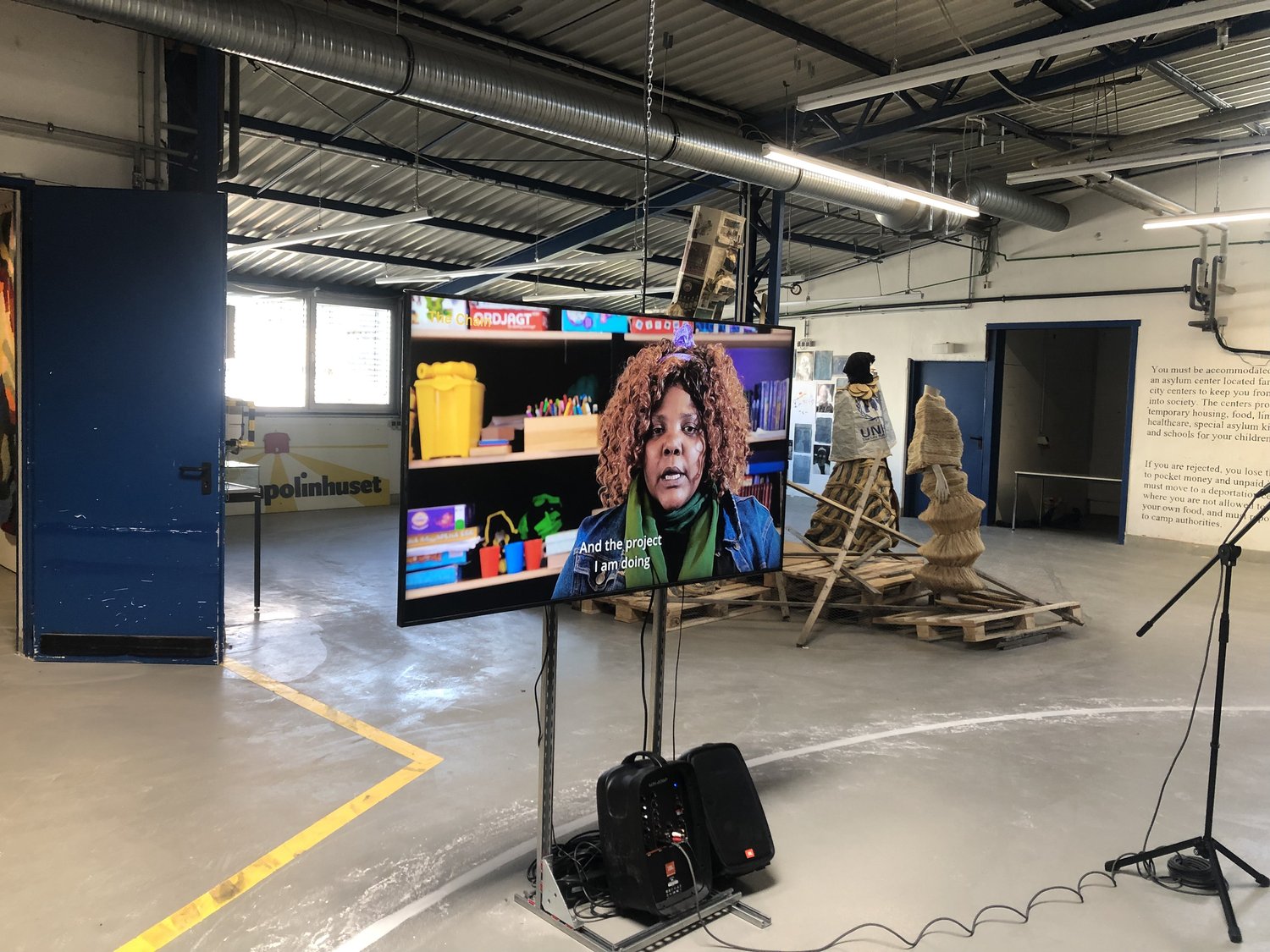

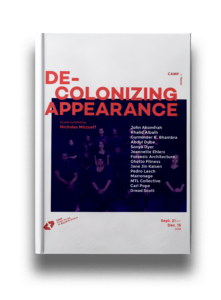

Trampoline House and CAMP (Center for Art on Migration Politics) are two Copenhagen-based initiatives that operate within this highly segregationist social and political context. Besides being a non-profit exhibition space, CAMP generates spaces of reflection and dialogue using political migration art as its outset. It works principally with artists with migration or refugee backgrounds, and the global outlook of its work is strengthened through its collaboration with renowned international artists. CAMP opened in 2015 with an art series that addressed the displacement of people, border regimes and the dehumanization of refugees and migrants. The overall aim of the centre is to exhibit art that can influence, challenge and transform Danish migration policies by addressing racism without excluding the migrant and refugee analytical perspectives and bodily experiences. CAMP is located in Trampoline House, which is known as the hub for refugees, asylum seekers and migrants, and as a pivotal space of community-building and resistance.

Trampoline House is a community house guided by communitarian principles and participatory practices, providing a space for learning, exchange, organization, struggle and (legal, psychological, social, educational) assistance to its users. The house was founded in 2010 as a result of the common work among asylum seekers, refugees, artists, scholars and journalists in their efforts to break the social segregationist tendencies dominating the Danish asylum system. Since its establishment, Trampoline House has been the epicentre of migrant, asylum seeker and refugee community-building and continues to be an important reference point—indeed a home—for anti-racist activism in Denmark. The activities at Trampoline House are shaped and defined in weekly meetings that work as spaces of collaboration that respect differential needs and priorities across the lines of citizenship, gender, age, race, class and residence status with the asylum seekers and refugees occupying centre stage.

The work of Trampoline House and CAMP can in many ways be seen as the complete reversal of the dominant Danish society’s white supremacist tendencies, where racist structures are de facto applied and defended. Indeed, Trampoline House and CAMP are notable for their commitment to decolonizing practices and principles, including a continuous endeavour to decentre whiteness in their daily practice. Run and co-founded by white Danish citizens committed to decolonization, these spaces are in a sense constantly in the making, significantly by practicing democracy in ways that counter the dominant Danish-nationalist understanding of democracy as inherently white Danish, and as inherently antithetical to the migrants and refugees who are involved in these spaces.

As such, Trampoline House and CAMP foster the community membership and democratic participation of people not simply as subjects of rights, but as agents central to the definition of these spaces and their aims. Within the framework of a colonial system that requires and indeed produces the illegitimacy of the migrants and refugees, Trampoline House and CAMP understand the vital significance of resistance as a way to exist politically and of political existence as a communitarian process whereby the immigrants, asylum seekers and refugees participate in the definition of their everyday lives and future projections.

Julia Suárez-Krabbe

¹ N. Leets Hansen and J. Suárez-Krabbe, ‘Introduction: Taking Racism Seriously’, KULT: Racism in Denmark, 15 (June 2018), 1–10; R. Andreassen, A. F. Henningsen, and L. Myong Petersen, ‘Hvidhed’, Kvinder, Køn og Forskning, no. 4 (2008), 3–8.

² J. Suárez Krabbe and A. Lindberg, ‘Enforcing Apartheid? The Politics of “Intolerability” in the Danish Migration and Integration Regimes’, Migration and Society, 2 (forthcoming, 2019).

³ R. Karpantschof, ‘Højrefløjen. Fra skattenægtere til racister’, in C. Fenger-Grøn, K. Qureshi and T. Seidenfaden (eds.), Når du strammer garnet. Et opgør med mobning af mindretal og ansvarsløs asylpolitik (Aarhus: Aarhus Universitetsforlag, 2003), 87–110; P. Justesen, ‘International kritik. Den nationale arrogance’, in Fenger-Grøn et al (eds.), (2003), 69–86.

4 J. Vedsted-Hansen, ‘Udlændingerettens grundbegreber, retskilder og myndighedsstruktur’ in Jacobsen et al., Udlændingeret: Indrejse, Visum, Asyl, Familiesammenføring (2017), 18.

5 Vedsted-Hansen (2017), 18; see also N. H. Larsen, ‘Afvisning og overførsel af asylansøgere’, in Jacobsen et al., (2017), 40–42.

6 Justesen (2003), 75