Feeling cannot be removed once it emerges.

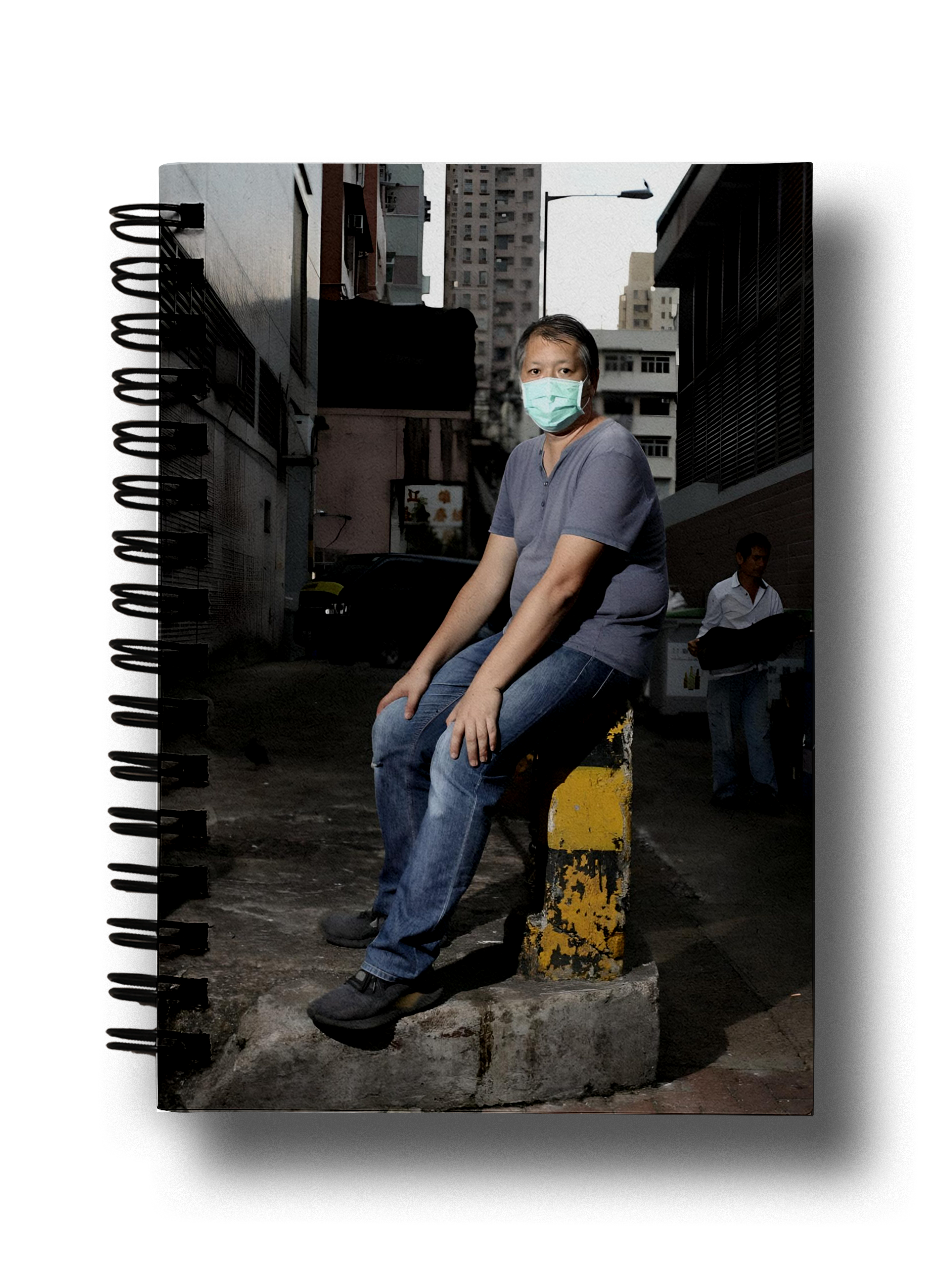

Luke Ching

Feeling is what motivates Luke Ching to create his work, take action and be involved in labour activism. Art is a form of expression and also a medium through which to influence the feelings of an audience. Luke Ching goes further than expressing his feelings, driving a social movement with the involvement of workers and viewers.

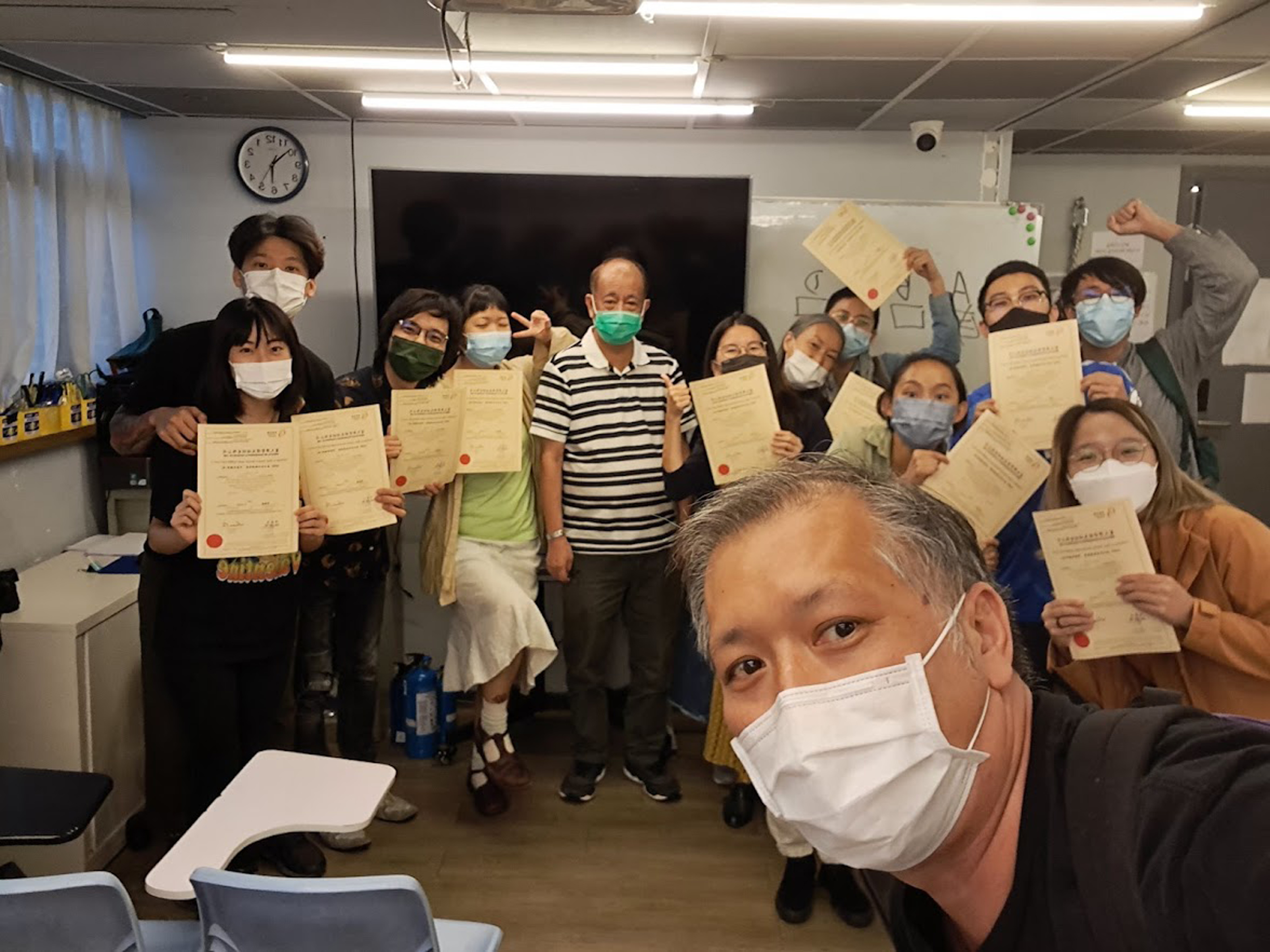

In 2007, Luke Ching started his journey after chatting with a museum security guard. He launched the ‘fight for a chair’ campaign for security guards in museums in Hong Kong. Ching collaborated with the local Hong Kong newspaper Ming Pao and published a survey on the salaries of art museum security staff. He has continued to explore labour issues ever since. A few years later, he became a security guard himself and the workplace became his field of ethnographic research. He documented his experience through ethnographic fieldnotes from the workplace, which later grew into different projects: the Undercover Worker project; the ‘workers after work supporting workers in working hour’ action group; and the ‘complaint about a chair’ consumer campaign.

In the Undercover Worker project, four people including Ching himself worked undercover in different jobs. The whole process was documented and published by a local Hong Kong magazine. The action group ‘workers after work supporting workers in working hour’ further transformed spectators/outsiders into actors in a labour campaign. By manipulating the complaints policy of chain stores, the consumer campaign ‘complaint about a chair’ successfully advocated for workers’ needs, combining a labour movement with ethical consumer activism.

Ching has been active at the intersection of these different fields: as a grassroots worker, an artist, a reporter and a social activist. Eventually, he has been able to remove labels and categories from society. His actions allow people to become people again—human beings with feelings, empathy and bonds with others. When switching between different identities, he is led by his feelings. Ching expresses his belief that workers’ rights are human rights. His works are not merely labour activism, but the result of a desire to motivate the humanitarian movement in Hong Kong, one of the most highly capitalized and dehumanized cities in the world.

It is not in human nature to put ourselves in the place of those who are happier than ourselves, but only in the place of those who can claim our pity.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Feeling leads to action

The emotion of compassion is generated by seeing others’ suffering. The eighteenth-century Genevan philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau posited that the emotion of compassion is a part of human nature and can be cultivated to bring individuals closer together. Rousseau believed that all humans can understand others when they see someone suffering. As we all experience similar feelings, the barriers among different social groups should no longer exist.

Ching felt compassion when he first talked with the security guard in the art museum. His curiosity about workers’ experiences led him to choose to immerse himself in the life of grassroots workers who face isolation in modern society. They perform dirty, difficult and dangerous jobs, usually away from the public eye. As workers have become isolated, they have lost the ability to express the hardships they experience. Ching describes this phenomenon as ‘workers’ aphasia’. Have you ever undertaken hard physical work for over twelve hours per day, sixty hours per week? Exhaustion and silence are the only two things left. The workers’ suffering can only be understood by workers themselves. By participating in these workplaces, Ching found that workers are led to normalize and adapt to their difficult situation.

By disclosing the unspoken details of workers’ daily lives, Undercover Worker aims to break down the barriers between workers and outsiders and to expose viewers to the alienation of labour and the hierarchy of labour relations. In the article One-Week Security Guard¹, Ching not only observed the daily duties of a security guard but also depicted his transformation from an artist to a security guard. For his job interview, he prepared to answer why as an artist he applied for the position of security guard. The interviewer showed no interest in him as a person but rather spent a significant amount of time fitting him into the roster. A job turned him from a man with a history and creativity into manpower that can be managed. This process of the dehumanization of labour ironically speaks to anyone who has ever had a job interview.

In what appear to be normal settings for workers in modern society, Ching is able to spot the ironic and represent it through narration. He has broken open the isolated world of grassroots workers in a metropolis like Hong Kong. In traditional labour movements, intellectuals go into factories and organize unions within them. Ching’s Undercover Worker experiment approaches this tradition from a different perspective.

Ching described the experience of being a security guard in uniform like cosplay. Without the mission of forming a union, he did not even think about rebelling from within. He just simply lived as a worker by dressing like a worker, acting as a worker, and thinking like a worker. From the emotion of pity to becoming one of the group, the Undercover Worker project performs a ‘synesthesia’ of the human.

We asked for workers. We got people instead.

Max Frisch

The art in everyday workers’ lives

Data never moves peoples’ hearts. It cannot represent the body of a worker, their family or their history. The narration of the undercover worker’s experience is touching, a humble reflection of the everyday life of workers. This first-hand experience has brought some issues to the surface that the outsider would not imagine.

When we drop rubbish in a bin, do we ever think about the process of cleaning up a rubbish bin, the follow-up process for workers that our piece of rubbish leads to? In Hong Kong, there are usually two to three bins on each street. Due to the poor design of the bins, cleaners have to pick up the heavy cover, turn it upside down to empty the ashtray on the top, pull out the plastic bag from the bottom, then cover it up again. Before Ching, no one had ever questioned the design publicly from a labour point of view. He began by putting stickers on rubbish bins in his neighbourhood, reminding people to think of the cleaners before they filled the bins up. Borrowing an idea from a cleaner, Ching then made aluminium bowls to put on the top of the rubbish bins as an ashtray, to save workers from having to undertake this heavy process. He later turned this into a campaign. Ching’s sensitivity to the workers’ situation highlights the alienation of the labour process.

Ching’s projects start with something small. For a security guard, a chair is his dignity. For a cleaning worker, an aluminium bowl on the top of a rubbish bin would make his/her routine smoother. Setting up a water cooler in a store could help the staff to be hydrated. Small deeds are not insignificant—these small details in the workplace could mean a lot to workers. A thousand miles begins with a single step. Ching’s projects are the first small step in the thousand miles of the labour movement.

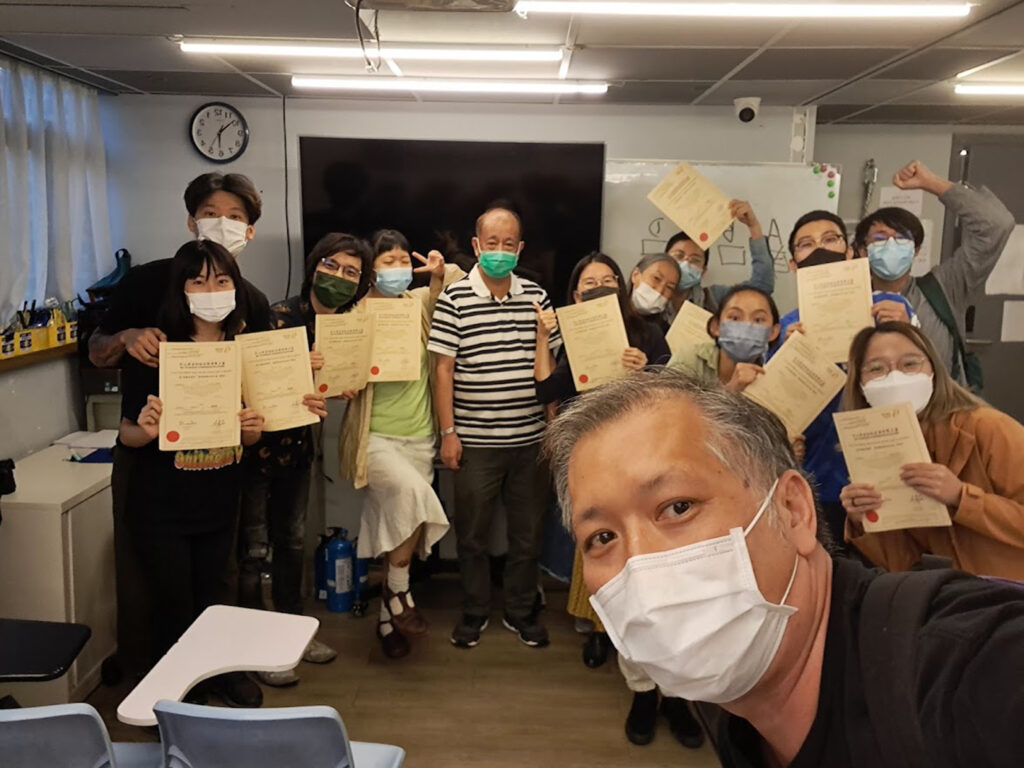

Voice for the voiceless

To address inequality and lead to action for change, workers have to know how to speak out for themselves. In traditional labour movements, workers use labour unrest; strikes and other forms of labour action are well developed in labour relations. In Hong Kong’s case, grassroots workers are in a vulnerable position. The precarious nature of contract-based jobs prevents them from taking collective action to protect themselves.

How is it possible to speak for the voiceless? Precarious workers in Hong Kong have lost their tools of expression within the context of labour relations. And what about outside this context?

Hong Kong’s economy is dominated by the service industry. Other than the three main traditional parties in labour relations—workers, employers and the government—the role of the consumer has not been emphasized. Ching formed an action group on Facebook named ‘Workers after work supporting workers in a working hour’ in order to utilize consumer activism.

Complaints systems are developed by management to control service-sector workers. There have been several cases in which a customer filed a complaint against a worker and the management immediately fired the worker with no questions asked. This system has been a public relations tool for companies in order to please customers.

Using big companies’ complaints systems, Ching aims to show the unity of workers. Most people are workers themselves— even customers are workers who are off work. If workers can’t use labour action as a way of speaking out for themselves in their workplaces, they can help each other out when they are outside work by utilizing their role as a customer. If consumers do not like workers having to suffer while they provide services for them, they are able to use the complaints system to express themselves.

The ongoing complaint campaign has successfully fought for seating and rest time for cashiers in several supermarkets, convenience stores and shopping malls. Ching has found that public shaming is a useful tool in the fight for workers’ rights. He wrote a letter to Times Square Hong Kong for an advertisement on its big outdoor screen, asking for chairs for UA cinema staff. He also held a slogan competition to urge Circle K convenience stores to remove the requirement for workers to wear a cap. Combining labour movement and consumer activism, Ching seeks to influence the service industry in the name of workers beyond traditional labour relations.

Luke Ching’s involvement in labour activism for over ten years started from a small deed, a particular, touching moment of exchange with a security guard in an art museum. Resistance is a rather passive concept. Creativity is key to create an alternative way of circumventing existing restrictions in the social system. Ching has brought fresh insight to the labour movement in Hong Kong by identifying the cracks in the modern labour economy and developing new creative tactics to generate a social impact. These impacts grew out of the emotion of compassion.

¹ The article was written by Luke Ching and published in Ming Pao Magazine in 2014. The title is translated from the original Chinese title, literally meaning “being a security guard for one week.”