Year

2019

Publisher

Verso

Author

Ariella Aïsha Azoulay

Annotation

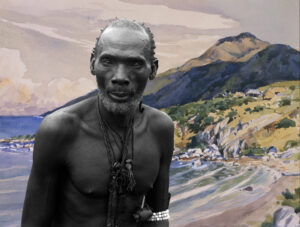

Historically, processes of decolonization and subsequent nation-building have often entailed leaders of the newly independent state aligning themselves with a Western-style conception of democracy, human rights and sovereignty. Jump forward to the present moment and the residual coloniality of power and being is evident across both the former colonies and colonial metropoles. In this global context (an often ‘unbearable imperial condition’), Ariella Aïsha Azoulay’s Potential History: Unlearning Imperialism is a rallying cry to ‘unlearn’ the political tenets and concepts of (neo-)imperial rule and to reconfigure an alternative origin for the discourse of rights. ‘Progress’ is shown to always occur at the expense of some, and ‘conditions the way world history is organised, archived, articulated and represented’ (p. 11). As Azoulay argues, the narratives that proclaim the progress of citizens’ rights disavow the violence of defining citizenship as ‘a constituent element of belonging to the state rather than as a shared trait of cocitizens caring for a common world’ (p. 39). Faced with this teleology of progress, Azoulay’s claim is that caring for a common world, ‘a shared world’, would entail a different temporality of history: one premised upon ‘rehearsal, reversal, rewinding, repairing, renewing, reacquiring, redistributing, readjusting, reallocating, and on and on’ (p. 56). The practice of ‘rehearsing disengagement’ is part and parcel of the ‘potential history’ of the book’s title: ‘a form of being with others, both living and dead, across time, against the separation of the past from the present, colonised peoples from their worlds and possessions, and history from politics. In this space wherein violence ought to be reversed, different options that were once eliminated are reactivated as a way of slowing down the imperial movement of progress’ (p. 43). Structured through thematic chapters, a series of historical moments, ‘rehearsals’ or ‘lessons’ from an array of locations (the Américas, Palestine, Congo, Algeria, among others) punctuate the book and serve as the potentialities from which Azoulay’s theses emerge. Returning to, lingering with and rehearsing these moments functions as modes of attending to— a term that appears frequently across the book — as a mode of retrieving and honouring. Of rewinding in order to give an account of calls, claims and formations that people have performed — in public spaces, no less — across the globe since the beginnings of imperialism. While some of the entries that follow (see Ferdinand, La Colonie) require literal carrying over from one tongue to another, here a different kind of translation is demanded, this time epistemic. The first book to be written by Azoulay directly in English, Potential History asks that we re-invest words that are all too familiar with alternative meanings and uses (I refrain from writing ‘new’ meanings, since, as for instance in Sovereign Words below, concepts such as ‘sovereignty’ have already been understood and practiced otherwise for a long time), that we unlearn their commonly assumed registers. For instance, institutions such as citizen, archive, art, sovereignty and human rights, as well as categories such as ‘new’ and ‘the neutral’. Together with this unlearning of familiar vocabulary comes the creation of a new lexicon: that of ‘nonimperial worldly sovereignty’, ‘worldly rights’, ‘rights as a worldly relation’ and ‘the condition of worldliness’. Through examples of practices of sculpture and photography, as well as debates around curatorial modes and restitution, a claim is made for the potential of art as ‘a world-building set of activities irreducible to the creation of discrete objects’ (p. 140). Key to the shared world in whose name Azoulay writes is the act of imagining. The invitation to imagine (or is it an imperative?) is encountered across the book’s 581 pages, and explicitly so in the five intermezzos: ‘Imagine Going on Strike: Museum Workers’; ‘Imagine Going on Strike: Photographers’; ‘Imagine Going on Strike: Historians’; ‘Imagine Going on Strike: The Governed’; ‘Imagine Going on Strike Until our World is Repaired’. While the term ‘public’ or ‘publics’ is not part of Azoulay’s chosen vocabulary, these small sections are invaluable for the practice of collective reading, unlearning and imagining in the informal assemblies, gatherings and protest spaces — be these within or without of the institutions that are the focus of Azoulay’s critique — that are currently taking place globally.

Shela Sheikh

Since the late eighteenth century, with the institutionalization of modern citizenship and the differentiation of people around the globe along racial axis separating citizens from noncitizens, the category of the citizen has become one of the most elementary components of the imperial condition. But it may also be one of the bases for overcoming this condition. This book is deliberately written from the position of a citizen, necessarily also a citizen-perpetrator, who is committed to the task of reclaiming a nondifferential, worldly form of cocitizenship situated in a shared world in need of repair. At the heart of this project lies an attempt to regenerate a discourse of rights from the ground of imperial violence as a reparative process of undoing the sedimented differences through which this violence is reproduced. Claiming the right not to be made a perpetrator is, was, and should again be a constitutive right of any political formation and guarantor of a substantial form of reparations. It is essential not only for any configuration of cocitizenship, but also for undoing the violence invested in objects, methods, and procedures so rights could be redistributed and their inscription in objects actualized. This book imagines and presents these rights as constitutive elements of civil alliances and worldly sovereignty.